What is the Indigenous Territorial Emergency Law that was extended for four years?

Law 26.160, the Indigenous Emergency Law, was about to expire, but its extension for four years was established by Decree 805, published this Thursday in the Official Gazette. Hate speech and racism resurfaced along with the law's expiration.

Share

[News updated on 11/18]

The escalation of hate speech in some media outlets and explicit racism against Indigenous peoples in Argentina has intensified in recent days, and this seems no coincidence. Political and business leaders are disseminating such messages, and various mainstream media outlets are maximizing their stigmatizing coverage. All this violence has accumulated less than a month before the imminent expiration of legislation that halts evictions from Indigenous territories.

Indigenous territorial emergency: what you need to know

In November 2006, Law 26160 , declaring an emergency regarding the possession and ownership of "the lands traditionally occupied by the indigenous communities of the country."

The bill arose from a collective struggle demanding an end to the constant evictions of Indigenous communities by private interests, as well as by state agencies such as National Parks and public universities.

The text of the legislation—known as the “ Indigenous Territorial Emergency Law ” —suspends all evictions involving Indigenous communities (registered with RENACI, the National Registry of Indigenous Communities) until a territorial survey is conducted. This survey must be carried out jointly by the national government, the provinces, and Indigenous organizations.

Specialized technical personnel from various disciplines (geography, surveying, anthropology, history, ecology, biology, law, administration, etc.) participate alongside representatives from the Indigenous Participation Council, the provinces, and the National Institute of Indigenous Affairs (INAI). It must always have the acceptance of the community where it takes place and the participation of its authorities and members.

That's the letter of the law. But what's happening in practice? Are they being implemented jointly? Why did it take so long?

Originally, this survey was to be completed within three years. It was subsequently extended three times: in 2009 (Law 26,554), in 2013 (Law 26,894), and in 2017 (Law 27,400). Its validity expires on November 22 of this year. If it is not extended again, it will become invalid.

Data and territories

According to the report from the National Program for Territorial Survey of Indigenous Communities (INAI) carried out on 10/15/21, these are some figures on the situation in the territories:

- Of the 1,760 Indigenous communities identified by the INAI's Land Directorate, 43.4% remain unsurveyed. Meanwhile, 56.6% are at various stages of land surveying.

- Of the total number of surveys actually completed, 61.8% corresponds to the Noa region, 15.8% South, 11% Nea, 9.8% Central and 1.9% Cuyo.

- In the analysis within the regions, the Nea is the region where the greatest lack of surveying is recorded (62.7%) and is followed by the South and the Noa, where 46.3% and 33.5% have not yet been surveyed, respectively.

According to the report prepared by the agency in 2017 (before the previous expiration of the extension), the provinces that at that time had completed the survey are Catamarca, Córdoba, Entre Ríos, La Pampa, Mendoza, San Juan, Santa Cruz, Santa Fe, Tierra del Fuego and Tucumán.

Provinces that have serious territorial conflicts with indigenous peoples such as Chaco, Formosa, Salta, Jujuy, Chubut, Santiago del Estero, Misiones, Neuquén and Río Negro are still delayed and with partial surveys .

Ancestral property and evictions

It is important to emphasize the pre-existing status of Indigenous peoples and their right to communal and ancestral property, as also established in section 17 of article 75 of our Constitution and ILO Convention 169. However, does the legislation actually stop evictions? What would the implications of its expiration be for the communities?

Beyond the spirit of the law and its objectives, in practice there were significant problems with its effective implementation in the territories. During these fifteen years, evictions were repeated in various parts of the country. Many communities were expelled from their territories either for not being registered as required by RENACI or because the province had not adhered to the national law. There were also reports of surveys conducted without the participation of the communities involved.

the law's validity also For this reason, various Indigenous organizations have been speaking out and mobilizing not only to demand an extension but also to call for an increase in the budget allocation and for a debate on the long-delayed law implementing Indigenous communal land ownership , which would allow for the recognition of this ancestral form of property under the Civil Code.

Provisional and precarious titles

Today, communities face serious problems with provisional and precarious land titles, which in their territories translate into the latent possibility of evictions or vulnerability to the advance of the business sector dedicated to agribusiness, tourism, and extractive industries . This structural situation is compounded by a climate of growing tension resulting from the sustained circulation of racist discourse in the media, which stigmatizes Indigenous identities and thus sets the stage for potential repression (as also occurred in 2017).

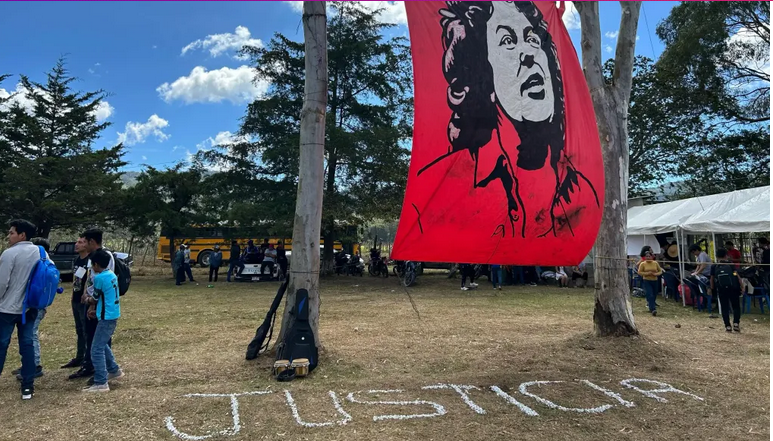

Throughout this month, demonstrations, marches, communication campaigns, and statements from Indigenous leaders and public figures have been held to demand the extension. Vigils will also be held in front of Congress to support its consideration.

Indigenous rights are the result of the resistance and struggle of Indigenous communities and organizations. But it is essential that society as a whole get involved and support these rights. Demanding the extension of Law 26.160 is a human rights imperative.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.

1 Comment