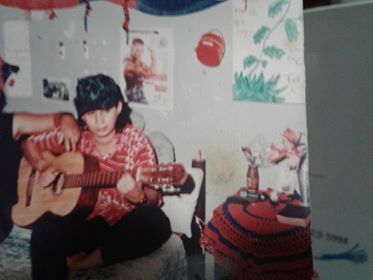

Chana Coronel, the lesbian who fought for conjugal visits in Paraguayan prisons

September 16th is commemorated as Lesbian Visibility Day in Paraguay in homage to Feliciana “Chana” Coronel, an icon of the struggle for the right to intimate visits for lesbians deprived of their liberty.

Share

Feliciana Coronel, or “Chana,” as she was known in the El Buen Pastor women's prison, was murdered in prison at the age of 33 under circumstances that were never clarified. But that is not why September 16th is celebrated as Lesbian Visibility Day in Paraguay. In 1993, Chana and her fellow inmates denounced to the press and judicial authorities the discrimination faced by incarcerated lesbians. They were not allowed conjugal visits.

Chana was from Chacarita, a Cerro Porteño fan, a single mother, a lesbian, and a rebel. But being a lesbian, poor, and demanding fundamental rights doesn't come without consequences in Paraguayan society. She had been incarcerated in the Buen Pastor prison in Asunción since 1991 for possession of a kilo and a half of cocaine. She was sentenced to 13 years, but her time inside did not go unnoticed. Chana's fellow inmates considered her a leader in the prison. She often spearheaded protests organized within the Buen Pastor and was therefore considered "extremely dangerous" by the authorities.

Clyde Soto, a feminist psychologist and social researcher at the Center for Documentation and Studies (CDE), brings Chana back into Paraguay's historical memory. She wrote articles on lesbian visibility in 1993 and 1996. In her piece "Chana: The End of an Anti-Heroine," published in Informativo Mujer , she recounts how not only were lesbians prohibited from having intimate visits, but also all women without husbands or stable partners. And those who were known to be lesbians were barely allowed to be together or even speak to each other.

Lesbians on the warpath

On September 17, 1993, El Diario, a newspaper of the time, published an article titled “Lesbians Demand Access to Private Room at Women’s Prison,” and the photo caption read: “Lesbians on a ‘war footing.’ ‘Chana’ and her companions threatened to resort to extreme measures if their demands were not met.” It was the first time the press hadn’t called them “dykes” or “tomboys.” “Never before had a woman or a group of women openly acknowledged their homosexuality, much less demanded equal and non-discriminatory treatment compared to that received by heterosexuals,” Soto notes in her article.

In the historical compilation “All My Life: Lesbian Memories in Paraguay,” released this year by Aireana, a lesbian rights group, they describe how, on that day, the inmates took advantage of a visit from Supreme Court officials to denounce the discrimination they faced within the prison. These were women who were not afraid to identify as lesbians or to claim what was rightfully theirs. That is why they chose September 16th as Lesbian Visibility Day, a commemorative date that also falls within the “Month of 108 Memories.”

“We were looking for a date to commemorate historical events. We didn't want it to be a murder or something sad, but rather something related to the struggle, to lesbians. And the newspaper headline at the time said: 'Lesbians on the Warpath.' We loved it because it's not a very distant time, but it's distant enough because in '93 there weren't any LGBT organizations. And years before that, it started with a group of lesbians who had nothing to lose,” recounts Rosa Posa, an activist with Aireana.

A historical LGBTI stigma

On July 4, 1996, Chana was stabbed to death in prison, and although the circumstances of her death were never fully investigated, newspapers at the time claimed she was murdered by her lover. This is not the first time in Paraguayan LGBTI history that the mainstream media has portrayed the deaths of gay, lesbian, or trans people as the result of “crimes of passion” or pathologizing relationships. In both the case of the renowned radio host Bernardo Aranda Serafina Dávalos the first lesbian and feminist lawyer , the same mechanisms of social control were employed.

“What the press has done, just like with Serafina’s case, is to assume that lesbian relationships are cursed, psychotic, or highly toxic, where obviously one woman has to end up killing the other. Serafina was the first female lawyer, but her death has to be shrouded in mystery because she was a lesbian. This idea that Chana was a lesbian criminal and was killed because everything in her life was wrong stems from the fact that she was on the margins of society, but we’ll never really know what happened. What we stand for is that she managed to organize with her comrades without prejudice or fear,” reflects Rosa Posa.

Chana had an 11-year-old son, Jose Carlos Coronel, at the time of her murder. This adds to the stigma faced by lesbians who are both incarcerated and mothers. It's not just because they break with the role of submissive wives and present mothers assigned to them by society, but also because of the lack of adequate laws and policies to address issues such as those faced by breastfeeding mothers or the children of incarcerated women. This is compounded by the already challenging conditions for women deprived of their liberty, such as overcrowding resulting from the increase in the female prison population, generally for crimes related to drug micro-trafficking.

Discrimination persists

Since 2011, Aireana has been supporting the fight for this right at the Buen Pastor prison, which houses approximately 95% of Paraguay's female prison population. They monitored the cases of several couples who requested this right but were denied by the authorities. Since 2012, a regulation has been in place that, by neutralizing gender, does not specify that the partner of the incarcerated person must be of the opposite sex.

Nearly 30 years have passed since Chana's protests at El Buen Pastor prison, but the right to conjugal visits for lesbians is still not being fulfilled. There is no legal impediment to accessing conjugal visits; rather, it is an arbitrary stance taken by the entire prison administration. In 2016, Aireana reported that several inmates were being threatened with transfer to other prisons. However, El Buen Pastor's internal regulations do not specify the sex or gender of visitors.

The then Minister of Justice, Carla Bacigalupo, defended the ban on private visits for gay and lesbian inmates based on Articles 51 and 52 of the National Constitution. However, the Constitution does not prohibit same-sex civil unions. Moreover, it guarantees equality of dignity and rights for all people. The courts appealed a law from the dictatorship era—which stipulates that inmates can only receive visits from people of the opposite sex—to overturn a 2012 law that establishes equal treatment for all incarcerated individuals.

According to Article 131 of Law 5162/2014 of the Criminal Enforcement Code, inmates who do not have temporary release privileges to strengthen and improve family ties "may receive conjugal visits from their spouse or partner in the manner determined by the regulations." The National Mechanism for the Prevention of Torture recommended that the Ministry of Justice implement the 2012 regulations on conjugal visits for persons deprived of their liberty without discrimination based on sexual orientation.

“This is not just a matter of freedom, but also of many human rights. Overcrowding, torture, and ill-treatment are common, and when sexual orientation and gender identity are added to that, it becomes an intersectional factor of aggravated discrimination,” the National Preventive Mechanism (NPM) states in the document they worked on together with other human rights organizations such as Panambí, Aireana, Akahata, and Global Initiatives.

“In 2012, the regulations regarding conjugal visits were changed, and the current regulations do not distinguish between the gender or sex of the visitor. But this government and the previous one are playing dumb (in Guarani, they're just playing dumb). They're bringing up things from the Stone Age, like this 1970 law, and they refuse to apply existing regulations. This is an example of how not all regulations are followed and how far we are from achieving legitimacy,” says Rosa Posa.

Thanks to Chana and her companions, pioneers in the fight for the right to conjugal visits for lesbians in the 90s, along with several other inmates. “Today we celebrate that lesbians dared to identify as such, to demand their rights from the authorities. This happened years before the organized LGBTI movement even existed, so we celebrate our place in history, that lesbianism is part of Paraguay's history,” Aireana celebrates.

Photos: personal collection of the Coronel Family recovered by Erwing Szokol.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.