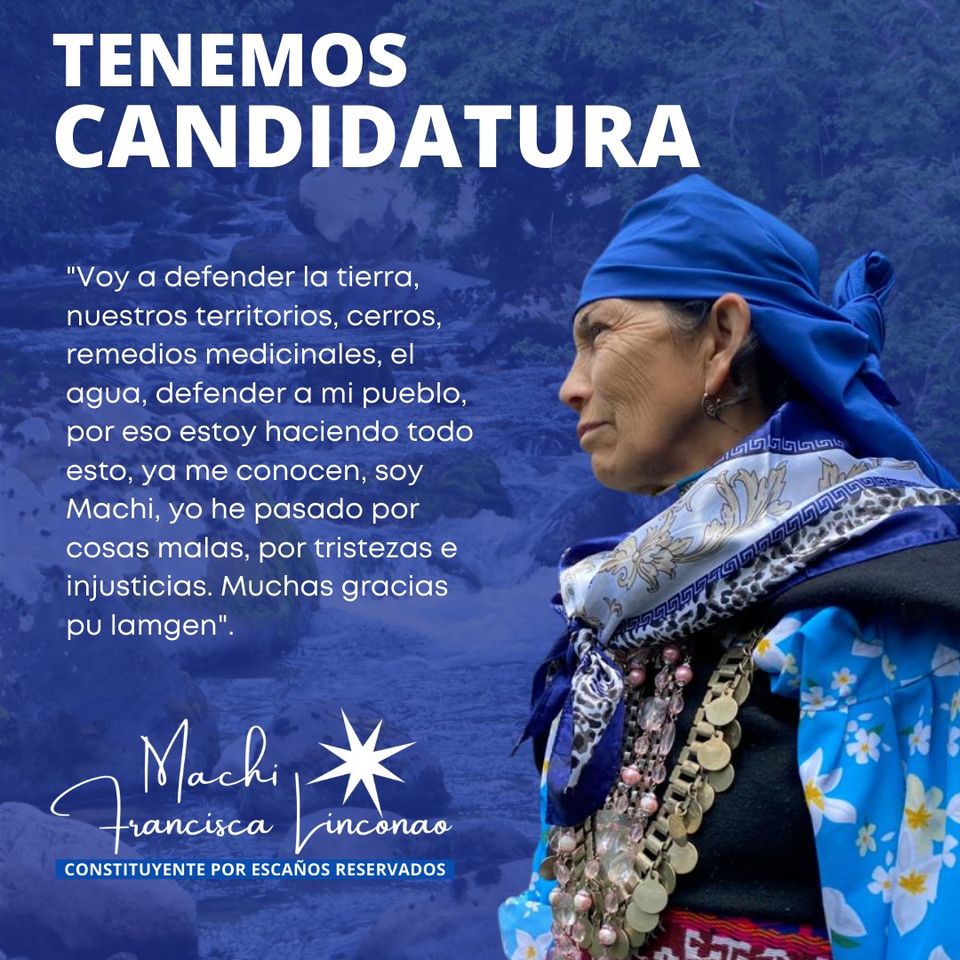

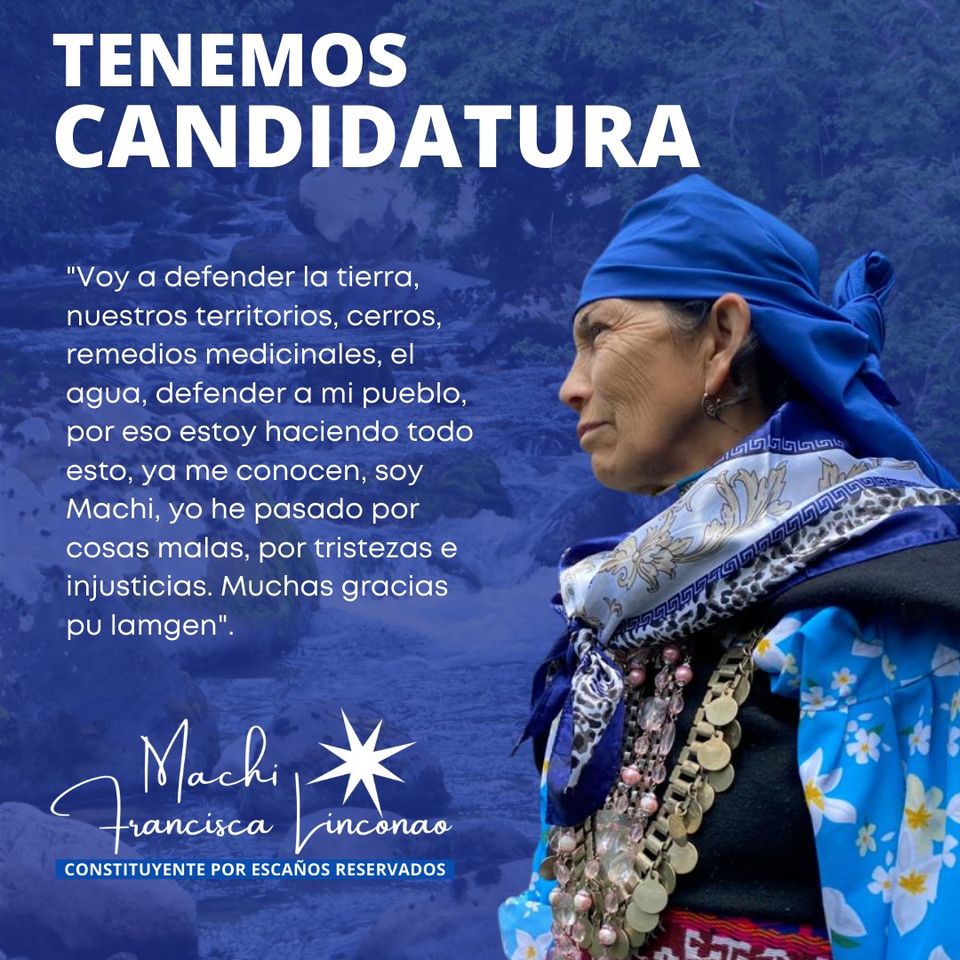

Francisca Linconao, the machi who will have a crucial role in Chile's new constitution

Francisca Linconao, an ancestral authority of the Mapuche people, was the most voted-for Indigenous candidate in May and will write Chile's new Constitution. Who is she and why is her participation a landmark?

Share

Photo: Juan José González/Machi Francisca Linconao website

At 65 years old, and with at least 13 years dedicated to a public crusade against the usurpation of territory, the destruction of the ecosystem, and the loss of Indigenous biodiversity, Machi Francisca Linconao was the most voted-for Indigenous candidate in the May elections to determine who would comprise the constitutional convention. This is a landmark achievement for two reasons: she is an important figure representing a historically marginalized and discriminated-against community in a country where the majority of its inhabitants prefer to disavow any Indigenous connection and believe that having a Mapuche surname can be detrimental in various aspects of life, according to a recent study by the University of Talca on racist discrimination in Chile. It is also significant because she is a woman who was prosecuted by the State on three occasions for crimes she did not commit, as the courts themselves concluded.

Of the 155 constituent assembly members, 17 seats are reserved for the ten Indigenous peoples of Chile recognized by the State. These seats were determined by voters from each Indigenous group who, regardless of their place of residence, chose to mark this ballot instead of the general ballot. Seven of these seats belong to the Mapuche people. The Machi (Mapuche spiritual leader) won the most votes among the 39 candidates, with 15,513 votes in 98.50% of the polling stations counted, representing 7.1% of the total votes cast for those seats.

The convention will convene on July 4th at 10:00 AM at the National Congress building in Santiago , following a series of legal and constitutional procedures. For Verónica Figueroa, a Mapuche academic at the Institute of Public Affairs of the University of Chile, the Indigenous presence at this event is a source of emotion and admiration. “It’s historic. It’s the first time that Indigenous peoples have participated in the life of the State. We had to force this participation because the existing mechanisms of representation didn’t allow it,” she told Presentes.

Her excitement over the machi's victory is twofold: “It's a milestone because of her crucial ancestral role. She bears a great responsibility for safeguarding and maintaining the balance of the Mapuche people, but she is also a political authority for us. What she proposes and the perspective from which she speaks carries great weight in relation to our people's own history.”

Unlike other Indigenous constituents, the machi is leading a cause that, according to the academic, will contribute significantly to the issues addressed at the convention. “It will be very interesting to see the role she can play, not only in leading some discussions, but also in educating Chilean Western society, which, among other things, is unaware of the protocols and arguments that underpin her authority.”

The story of the machi

According to the biography available on her candidacy website —created with the help of a team—Linconao dropped out of school in the fourth grade because she began to "receive" the calling of a machi (Mapuche healer). At age 12, against her will, her parents dressed her in a chamal (traditional Andean shawl). "I cried a lot because I didn't want to be a machi. I wanted to continue studying; I had a very good memory," she said in a 2018 interview with The Clinic.

At 16, he planted his rewe, a wooden totem pole built by each community from their oldest oak tree, symbolizing the connection between earth and sky. There, they perform a renewal ceremony that links their energy with that of the spiritual universe.

But in Chile, the machi has been publicly known since 2008, when she won a landmark lawsuit against a forestry company for the illegal logging of native trees and shrubs and the loss of medicinal plants in La Araucanía, in southern Chile. The machi spoke out not only because she witnessed a practice harmful to the environment and ecosystems, but also because the elements at stake are vital to the balance of her work and the role she plays in her community.

“I’m worried about the land, I’ve always said so. There’s no land, no water, and the families in our community have children, they get married, and we no longer have any land to build houses on. The Spanish and the colonists took all our land. We have to talk about that,” the machi told Radio Biobío in an interview after learning the results of her election victory.

The ruling that brought her case to light represented the first application of the International Labour Organization's Convention 169 in Chile. Article 13 of the Convention establishes the State's obligation to respect the cultures and ways of life of indigenous peoples and recognizes their rights to their lands and natural resources. Since then, she has been persecuted.

In 2013, Werner Luchsinger and Vivianne Mackay died in a fire near the community where the machi still lives with her family. The courts accused her of gathering 30 people at her home to plan the attack. She was imprisoned, went on a hunger strike, and was later placed under house arrest until she was declared innocent.

Three years later, in 2016, the case was reopened and the machi was imprisoned again. In 2017, she was acquitted once more. And in 2019, following the national protests that led to a political agreement for the drafting of a new Constitution, the machi began to consider and study what her contribution could be in this context.

A crucial role in the convention

In the constitutional referendum in October, 80% of the population voted to change the existing constitution, with a 50.91% voter turnout. The convention to be convened in July is a result of this. In its first session, the delegates will have the task of electing a president and vice president by an absolute majority. The name of the machi (Mapuche spiritual leader) is being mentioned.

Jorge Baradit, writer and elected representative for District 10, recently proposed her on a program broadcast by CNN Chile: “Whoever presides over the constitutional convention must be a woman, must be independent, must not belong to any political party, and must not be a member of the elite, not even from academia. She must also represent the reality of Chilean identity, that 80% who triumphed. (…) That is why my candidate is the machi Francisca Linconao.”

For Claudia Ancapán, a trans woman, midwife, and Mapuche woman, the machi can contribute wisdom from that role, because of her history and all she has lived through. And although she regrets that the convention will be convened without trans representatives, because they did not win a seat after the election, she celebrates the machi's achievement because, in a way, she too represents dissent.

“The machi is the embodiment of the concept of criminalization. I feel a strong connection to her story because we are both victims of violence, albeit in different ways,” she tells Presentes, recalling her transition and how difficult it was to break into the healthcare field because no one accepted her. She adds, “What I love about her is that she took misery, ridicule, and harassment and transformed it into social work, into a form of representation, and there she is: established by a majority vote for the convention.”

For Figueroa, understanding the history of the machi is also fundamental to understanding the weight of her figure in this context. “She represents the demands that the Mapuche people have tried to place on the political agenda during the last few decades, and she will bring those particularities to the discussion of the Constitution,” he analyzes.

One of those issues is language. He already made that clear. In a press conference broadcast live on his Facebook account , he stated that at the convention he will not speak Spanish but Mapudungun: “I will continue speaking my language, because I am Mapuche, because I am a machi. I will continue speaking like this, and if the winka doesn’t understand… that’s their problem, it’s the State’s problem.”

“That position is very interesting, very political, because it is the State that must take responsibility for that invisibility, that discrimination and the historical exclusion it has had with indigenous peoples,” Figueroa argues.

Proposals of the machi

On her website, the machi has a manifesto explaining that she embarked on this political journey out of a sense of responsibility to her people. “I am a traditional Mapuche authority and I can offer my kimvn (knowledge), rakizvam (thought), and pewma (dreams) to this historical process. That is the spiritual mandate I have: to guide my people and anyone who needs it ,” she writes. She also believes that the debt owed to Indigenous peoples must be repaid.

One of the proposals in their platform is the recognition of plurinationality , so that power can be reformulated “based on the right to self-determination of peoples.” Other proposals include the recognition and guarantee of human rights, especially civil, economic, political, environmental, social, and cultural rights; the right to a good life, to water, and to land, because “Indigenous peoples have experienced the dispossession of their territories, first by the State, and then by extractive companies”; the right to political participation and representation of peoples and social movements; and the right to food sovereignty and common natural resources.

“What is expected of her,” Ancapán believes, “is that she will reach agreements so that the new Constitution finally guarantees recognition of the Mapuche nation-state, indigenous languages, respect for difference, and reparations from the Chilean State towards our native peoples.”

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.