Nine years of the Gender Identity Law and one debt: to be on the country's emotional agenda

Passed in 2012, Argentina's Gender Identity Law was a pioneering law worldwide. What impacts did it have and continue to have, what opportunities did it open up, and what challenges remain?

Share

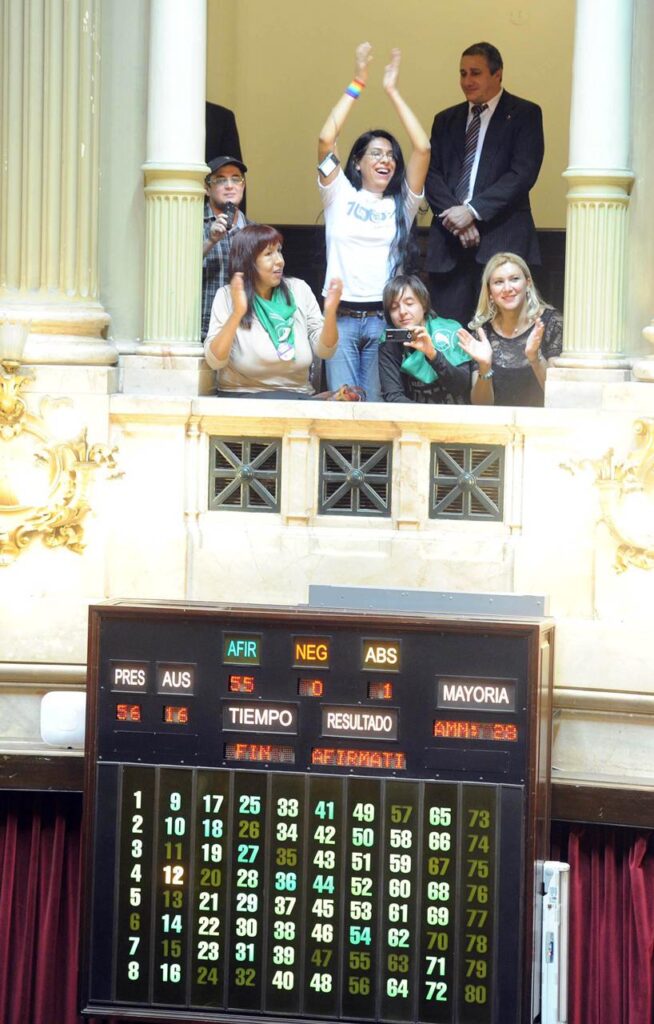

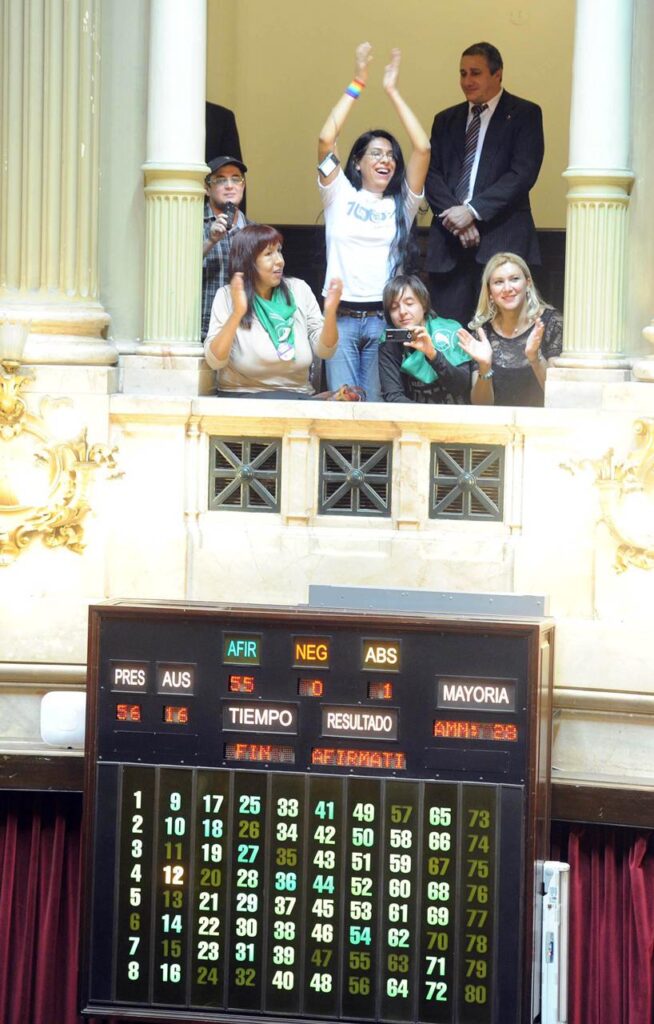

In May 2012, when Argentina's National Congress passed the Gender Identity Law (LIG), trans activist Alma Fernández was homeless. She lived in Plaza Flores, in the city of Buenos Aires, and survived, as many trans and gender-diverse people in Latin America still do today , by working as a prostitute. “I felt that for the first time there was a state present. A state that was giving us back our dignity and allowing us to go out into the open. But I wasn't participating in the debate forums because I couldn't read or write. Only after I got an ID was I able to finish primary and secondary school,” says the activist, who arrived alone at age 13 from Tucumán, a province in the north of the country with high levels of patriarchal violence. Today, Alma is a visible figure in demonstrations and in the fight for trans rights.

The Gender Identity Law (26.743) is unequivocal. “Every person has the right to recognition of their gender identity; to the free development of their personality in accordance with it; and to be treated accordingly.” Created and fought for in the streets by transvestite and transgender activists and the LGBTQ+ community, it takes a comprehensive approach and does not mandate any surgical intervention or require permission for recognition . Nor does it establish the obligation to change one's legal documents to access these rights.

“The Gender Identity Law (LIG) gave us the identity we feel. And it gave us rights. Before, we couldn't access them because we had documents with male names, and we were women, or vice versa,” says Magalí Muñiz , a member of the Trans Memory Archive . At 57, Magalí is a survivor in Latin America, where the average life expectancy for a trans woman is around 35 years . Magalí experienced criminalization and police violence, which was especially brutal against trans women and transvestites who engaged in sex work. But she also knows about resistance, about encountering each other on the road, in police station cells, in exile, at wakes. “The LIG was also very important because, starting with one right, others emerged: the right to study, the right to work ,” she says.

“When the law was passed, I was a cisgender lesbian, an activist for LGBT rights, and also a union member. At that time, I participated in street protests, and it seemed to me like a right in which I was being an 'ally.' The fact that we achieved that law helped me think about how my identity was intertwined with masculinity, and three or four years later I began my transition,” says transmasculine activist Ese Montenegro.

Self-perception, the backbone of the law

The right of every person to be and to express that right is the crucial freedom enshrined in the Gender Identity Law (LIG) passed in Argentina. Unlike in other countries, the focus of the debate was not on whether self-perception meant erasing other identities or whether it could be used to usurp rights . That conceptual battle had already been waged in the streets by activists like Lohana Berkins, Diana Sacayán, Mauro Cabral, Marlene Wayar, and many more.

“Self-perception was a topic that was debated in a very limited way, because it was tied to a particular notion of the State,” recalls Alba Rueda . Today, the activist from Mujeres Trans Argentina (Trans Women Argentina) is part of that State: she is the Undersecretary of Diversity Policies at the Ministry of Women, Gender and Diversity, created by the government of Alberto Fernández . Rueda participated in those preliminary stages leading up to the law's approval. “We were under a government [that of Cristina Fernández de Kirchner] that conceived of a certain type of State. Talking about people's personal development according to their felt identity was the most consistent approach with the logic of a State that should safeguard rights and not stigmatize or categorize .”

Why is Argentina's Gender Identity Law (LIG) often considered a pioneer? "Because it was the first to dare to break with somewhat conservative and traditional legislative logics, focused on biological elements —that the person resembled the gender they wanted to modify biologically, whether after some hormonal treatment or surgical operation—and pathologizing elements"—that every decision to modify gender was the result of several reports and psychological interventions—answers Marisa Herrera, PhD in Law, researcher at CONICET and professor at the University of Buenos Aires and the National University of Avellaneda.

In Argentina, the right to identity has a long history of struggle for human rights and even its own day of commemoration: October 22nd, the anniversary of the founding of the Grandmothers of Plaza de Mayo . It is linked to a crucial legacy: the Grandmothers' fight to recover more than 500 grandchildren stolen by state terrorism. “The development and consolidation of human rights, and especially the right to identity, directly linked to privacy and the free development of personality, was decisive in enacting a law whose backbone is the notion of 'self-perceived identity.' That is, the free and informed decision of a person before the civil registry—an administrative, not judicial, body—to change their gender without having to prove any requirement that such will exists,” explains Herrera.

“ I believe that the right to identity is a human right. We live in a world where the concept of identity is often debated, and it is one of the central themes around which we develop our lives . I think that society changes. In my family, in my neighborhood, it was something very foreign to my daily life, for example,” adds Ese Montenegro.

The Gender Identity Law (LIG) had an impact on other regulations within the Argentine legal system. “By challenging the binary male-female principle, since this law does not limit or circumscribe gender change within that binary logic, it allows individuals to step outside of this dual category, requesting the removal of any reference to gender if they do not identify with either [ the first case was filed in 2018 with the Mendoza Civil Registry ], or to self-identify as a ‘ transvestite femininity ’ [a case brought before the courts and currently under review by the Federal Court],” Herrera continues. In this broader and more pluralistic context, in accordance with the 2017 Advisory Opinion of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, “several regulations follow this logic. For example, the law on voluntary termination of pregnancy not only refers to the right of women to access this medical procedure, but also to all people with the capacity to gestate,” Herrera adds.

Gateway to more rights

Victoria Stéfano lives in Santa Fe and was 19 years old when the Gender Identity Law (LIG) was passed. “ The main impact has been symbolic, not statistical . For a generation of transvestites and trans people, the LIG meant beginning to have the possibility of engaging with the institutional life of a country. We were no longer foreigners in our own land . We were recognized as Argentine citizens, subjects of rights. That opened the debate about other rights that had been systematically denied to us,” she says. And it meant a concrete change in the lives of transvestites in general and in Victoria's in particular, who had just finished high school. “Having that groundbreaking law meant a change of perspective. It motivated me to study: to arrive at my training institute with my ID, with the name I had chosen,” says Vicky, now a transvestite journalist and a student of Social Communication. “Without that law, I wouldn't have continued my education, nor would I be the person I am now. This is what happens when the State recognizes your existence.”

What impacts did the law have in other dimensions? “It facilitated the management and thinking of public policies. That has to be present in any transfeminist policy project. And the foundations of information systems of the binary State are changing, although there is still a long way to go ,” says Alba Rueda.

The trans official also highlights the impact in social and cultural terms. “The Gender Identity Law was crucial for making visible and constituting political subjects. It was a victory for social movements that made a very valuable difference in addressing transphobic murders , questioning living conditions and vulnerabilities, and changing them from a political perspective in dialogue with the State. Today there are initiatives for trans and travesti employment quotas [like the Diana Sacayán Law approved in the province of Buenos Aires] because there is a gender identity law,” she explains.

In September 2020, Argentine President Alberto Fernández, in a historic decision, decreed a quota of at least 1 percent in positions within the National Public Sector "for transvestite, transsexual, and transgender people ." Two weeks ago, a voluntary registration system opened for those wishing to apply for these positions nationwide. Meanwhile, the National Congress began debating a series of bills submitted by sexual diversity organizations and transvestite and trans activist groups seeking to enshrine the employment quota into a national law for the comprehensive inclusion of transvestite and trans people. On Saturday, February 20, a "federal and plurinational demonstration" was held to demand its swift passage.

“The law came to alleviate the pain of exclusion, the frustration, the lack of motivation because the document had a name that wasn't yours. Having an ID with your own name was important for accessing rights, for studying and working, because before we couldn't,” says Alma, who now rents, lives in Villa 31, and divides her time between activism and various jobs, because one isn't enough to make ends meet. “The law is a child that's almost nine years old. We know there are still a lot of things missing,” she says.

Debt: being on the country's emotional agenda

More than a year ago, on February 13, 2020, the President of Argentina presented the 9,000th amended identity document to a trans woman, Isha Escribano . “Today we are a little more equal,” said Alberto Fernández in a speech that was seen as a political endorsement from the new administration for the trans and travesti population.

The Gender Identity Law (LIG) enabled rights and political participation for trans and gender-diverse people in society, but life expectancy, almost a decade later, remains at 35 years. These are opposing social forces: on the one hand, visibility and a cultural shift in many sectors, and on the other hand, the violence and deprivation that continue to be commonplace. According to the National Observatory of Hate Crimes , in 2020 alone there were more than 100 trans deaths, including both transphobic murders and social transphobic murders —that is, deaths due to state neglect, lack of access to rights such as healthcare, and structural violence. But these crimes and deaths, which have not ceased, do not have the same social impact as, for example, femicides.

“Our deaths matter too, and it’s necessary to make them visible,” said Marcela Tobaldi , coordinator of La Rosa Naranja, a civil association made up of trans women and based in Buenos Aires. In January, La Rosa Naranja published its own “ Statistical Report on Transvestite, Transsexual, and Transgender Women During 2020. ” According to this data, last year at least 10 transvestite, transsexual, or transgender women were killed in hate crimes, one trans man died by suicide, and 97 socially preventable transvesticides occurred. “The media highlights femicide statistics but never mentions social transvesticide, nor our hate crimes. And sometimes, when they do, it’s poorly handled,” Tobaldi told Presentes.

The ninth anniversary of the law's approval this year arrives with an unresolved demand: to know where Tehuel is and what happened to him. The young trans man left his home in San Vicente (Buenos Aires province) on March 11, 2021, to meet someone who had promised him a job as a waiter. Two people have been arrested but remain silent , and little to nothing is known about his whereabouts. The mainstream media has not supported the search. The justice system is investigating, but organizations are demanding that a gender perspective be applied, not a binary, heterocispatriarchal approach.

“ The law is ours, and it's not a failure. What failed was inclusion, the implementation of the law. We still have the same life expectancy as eight years ago. And we're not on the country's emotional agenda. It's true that there are more children living freely. But more than 80 percent of transvestites and trans people are on the streets. And the pandemic laid bare that reality. While TERFs argue , we continue to survive. I'd say they're almost complicit in every transvesticide,” says artist Susy Shock.

In this regard, Magalí Muñiz emphasizes the importance of passing a reparations law for trans survivors, one that acknowledges the historical violation of their rights and materially dignifies their lives. “There’s still a long way to go because it’s not being implemented as it should be: in healthcare, housing, and employment. We’re on the right track, and we continue fighting . Now, we need reparations for older generations. Older trans people continue to be excluded from every system .” Since 2017, trans and travesti collectives have been seeking the approval of the “Recognizing is Repairing” , and in the province of Santa Fe, there was a specific policy of historical reparations for trans people over 40. “Today, we have more robust tools than before 2012 to change our living conditions. There’s still a long way to go, but that long way is related to historical debts. To a certain extent, political changes prevented more profound reforms from taking place,” adds Alba Rueda.

A law that is essential for transvestites and trans people, and for all people.

Unlike other countries, such as Chile, where a gender identity law was passed that does not include children , Argentina's Gender Identity Law (LIG) integrates children and adolescents , following tireless advocacy by many families, supported by LGBTI+ activism. One of the causes of the 35-year life expectancy is the exclusion of these vulnerable trans children, first by their families and then by educational institutions. The inclusion of these children in the LIG and the development of inclusive policies at the educational level have the potential to change the lives not only of young people but also of society as a whole.

“The Gender Identity Law (LIG) is important for children and their families because it not only recognizes children's identity, but also provides a framework of respect. It's even a form of reparation for people. At least for Luana, that's what it was. Having that ID card that recognized her identity and made people respect her allows her to say: this is who I am. The LIG is essential not only for trans and gender-diverse people but for everyone. It made us think about where and when to start talking about gender identity, to begin questioning the binary, patriarchal system. It's extremely comprehensive and gives children and adolescents their rights and voice,” says Gabriela Mansilla , Luana —Luana being the first trans girl to legally change her ID in Argentina—and founder of the Free Childhoods Association.

Today, artists and activists like Susy Shock, Violeta Alegre , and Marlene Wayar are focused on supporting and protecting these children throughout their lives, not only legally but also emotionally and experientially. Comprehensive sex education—with the implementation of a law on the matter—is a crucial ally in ensuring that the rights of these young people are respected in all aspects of life, so that going to school, a health center, or even a public park does not become a violent ordeal. The work of raising awareness is ongoing and highly uneven across the country.

“Trans people are always imagined as adults. They also imagine us in certain times and places: the night, the street, the so-called “red-light districts.” We appear in the police sections of the media, in news stories with stigmatizing headlines, or as buffoons on television. In the libidinous realm where we have been placed, the world interprets our lives by recording our bodies, our performativity, which still provokes abjection and moral panic, without any kind of understanding of our lived experiences,” says trans activist Violeta Alegre.

For Gabriela Mansilla, one of the main myths that needs to be debunked in the future is biological determinism: “The idea that having a penis makes you a man, or having a vulva makes you a woman, and that's that. The law requires us to call people by their gender identity, but many people still think you're something else. The hardest part is the cultural aspect, the deeply ingrained, the established norms . I'm fighting for something I don't know if my daughter will live to see, but at least we'll leave a message for future generations. That they have jobs, education, that someone truly loves them. Having an ID still doesn't protect them from anything, which is why we need a cultural shift.”

*This article was originally published in Pikara magazine , as part of our partnership with that publication.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.