Lia García, the Mexican writer who narrates trans childhoods

"It's very important that trans people write our own history and that we are the protagonists of it." Interview with Lía García, educator, artivist, and transfeminist writer, author of Childhood Fighting the Virus.

Share

Lia García is a trans-feminist educator, artivist, and writer originally from Mexico City. She has lived here for all 31 years of her life, and it has been the place where she has fallen, risen, sown seeds, blossomed, and reclaimed the sea. “I am a mermaid. And when I say it, I reclaim the power of imagination because we've been told that imagining is for crazy people. And we, trans people, disobey when we imagine new worlds, new desires, new paths .” This is how Lia begins to tell her story.

For more than ten years, Lia has been committed to building pedagogical and artistic processes based on affection, radical tenderness and "desexualized touch" in encounters with trans children and adolescents, young people in public secondary and high schools and with people deprived of their freedom.

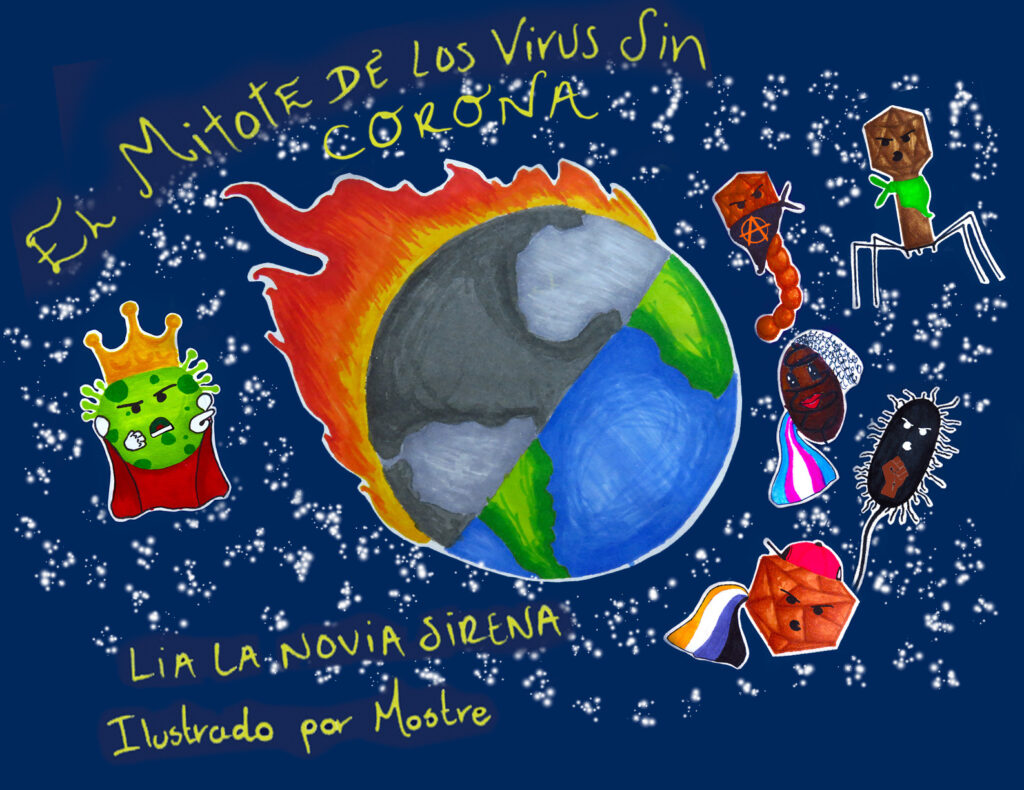

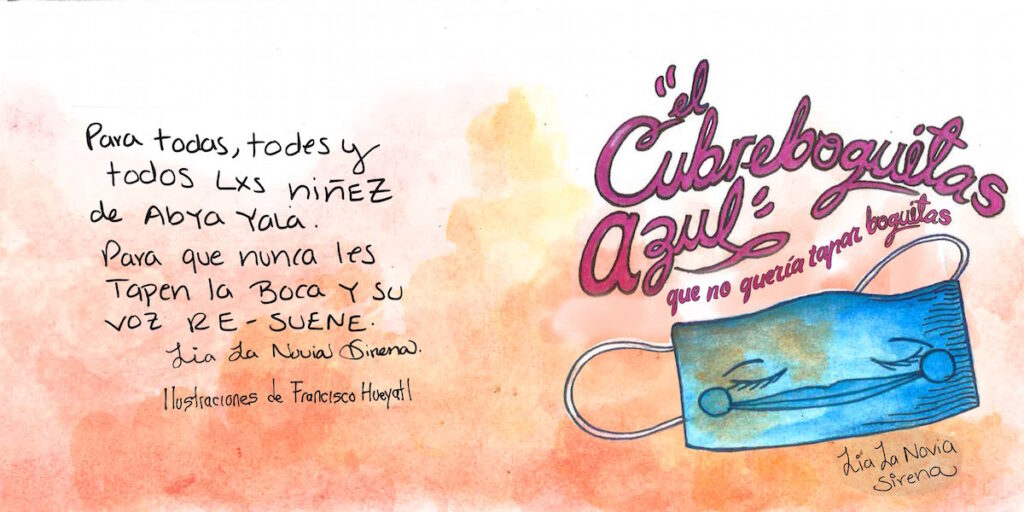

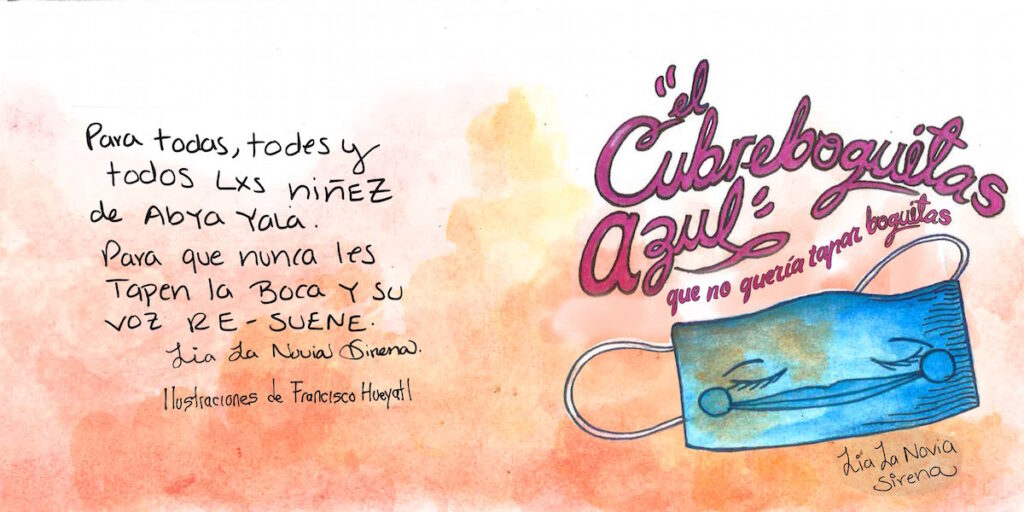

We spoke with her about her writing, childhood, and her literary project, Childhood Fighting the Virus . It's a series of five stories, conceived as a tool . "Because the literature surrounding this virus and aimed at children doesn't reveal how it also has implications for the body, for society, and for racist, transphobic, and classist violence throughout Latin America."

Lia was four years old when she began to find her voice in the water. Her uncles threw her into a river and warned her—almost as part of a male ritual—"This is how you have to learn because this is how men learn to swim." She did everything she could to stay afloat, moving to avoid sinking, but at one point she felt she was drowning. Lia remembers that in the struggle to survive she thought, "If I drown, I'll become a mermaid." That moment, the water, and the half-human, half-fish figure became the epicenter for her to reclaim her voice through writing, oral storytelling, and the body.

Trans writing for children

-What does childhood represent for you?

–Childhood is that space full of possibilities, of radical tenderness. Of an expansive imagination that shouldn't have to be taken away. The normative colonial state has even taken that from us, making us believe it's over when it's happening all the time.

For me, as a trans woman of color with Afro-descendant roots, it's very important to return to my childhood. To connect with it and heal wounds that were left open, not necessarily with the goal of closing them, but of experiencing them and listening to them. I think that's why I decided to write children's literature. It's a way of returning to that place.

-What is radical tenderness and how does it manifest in your daily life?

–It's a political act, the moment we return to childhood to dialogue with our inner child. The act of feeling tender, of crying with joy, of laughing with your friends, of returning to that vulnerability. Tenderness is linked to the small, the sublime. One of the most powerful political acts in this world is to be vulnerable, but doing so is difficult because it requires recovering our memories through our emotions.

"It's important that trans people are close to children."

-Why did you decide to write about children?

-Because children haven't had the opportunity to have contact with trans people . And for me it's also important that trans people are close to children, and that writing fosters that emotional connection.

Writing and oral storytelling are tools that allow us to connect. This way, we can open up our world and who we are to cis and trans children. It's very powerful because it's still inconceivable that a trans woman would be around children telling stories because of the doubt. There's a fear related to sexuality; we're still associated with abuse, and it's awful to be put in that position. So this opens up new ways of critiquing the world, and that's probably where the fear lies—that we're opening up the possibility of transition. That's what the world is most afraid of: transition.

-What happens when trans people decide to let go of their hands and write?

In a colonial world where we have been treated as subjects of study and our lives have been exploited, it is crucial that trans people write our own history and become its protagonists . By writing, we fight against that. Everything we trans people write is affective writing because it breaks with the structure that has told us we cannot exist.

The blank canvas is a space of resistance. Sometimes we are like that blank page because we don't know what to say in the face of so much violence. However, later we begin to write our stories and experiences.

-At a time when almost everything has become digital, why did you decide to write these stories by hand, and what does that entail?

Because I'm interested in writing being a living testament to the body . In this country, which is second in the world in killings, primarily of trans and feminized people, we have to bear witness that we are alive. Writing by hand and making it visible is a testament to that, to the fact that I am in motion . And it's beautiful because you can see the mistakes, the spelling errors, the imperfections. It's a testament to life because in life I can feel like I'm a mistake, that I feel crooked, or that maybe I'm on the right path where there will surely be falls, but not all of them necessarily hurt. And with this, I intend to give confidence to the girl, boy, or child who reads my stories . It's important to me that they feel they can make mistakes and that it's okay.

The stories reached indigenous communities

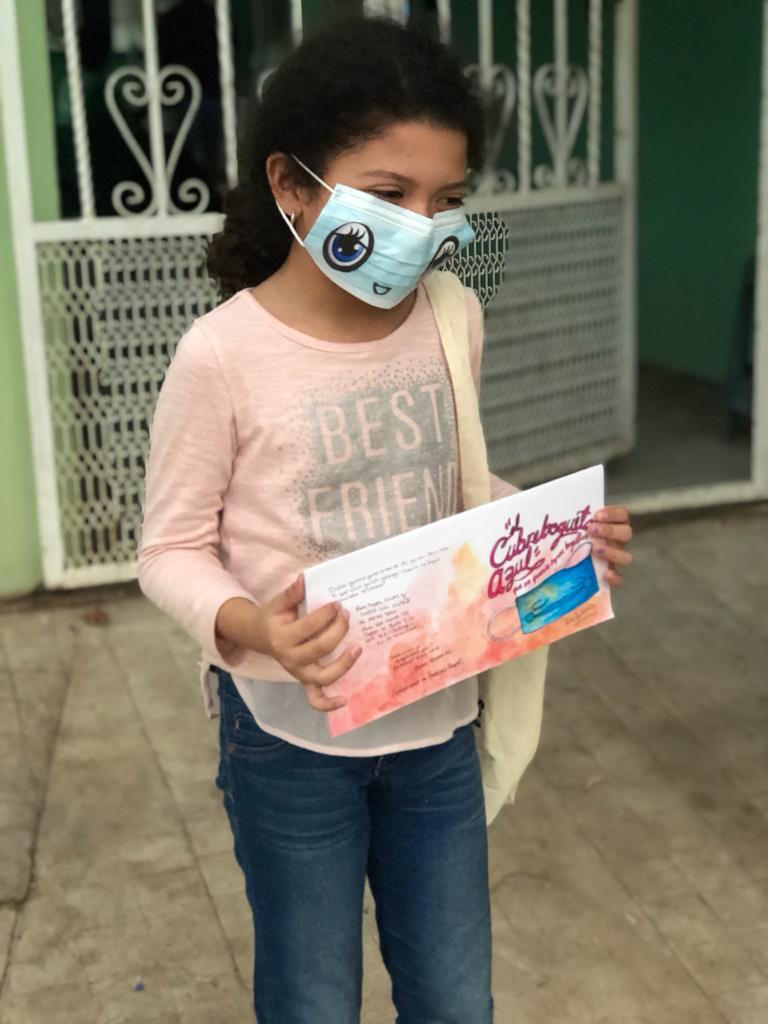

The series was translated into Tzotzil by the indigenous poet Xvet (Ruperta Bautista) from the Tzotzil Maya territory in Chiapas. And the story of “The Little Blue Face Mask That Didn’t Want to Cover Mouths” was translated into Zapotec and Chontal, indigenous languages spoken in Oaxaca, by teachers Esteban Ríos Cruz and Luis Ángel Leodegario, respectively.

“Lia’s texts were written in the Kaxlan (mestizo) language, a culture completely different from the Tsotsil Maya culture, where the concept of trans, face masks, or some other phrases don’t exist. And for that, another word was used so that it would be understandable in Tsotsil Maya,” Xvet told Presentes.

The books were taken to the communities of Asunción Ixtaltepec Oaxaca, Santa María Xadani, Santa Teresa de Jesus, Tehuantepec, San María Petacaltepec and Santa María Zapotitlan thanks to the artistic and child-working network, Binni Bianni .

The self-managed bookstore La Reci was in charge of editing and printing the stories. “It was Rosa’s (La Reci) idea to translate the texts because it’s necessary for them to be accessible to children living in non-centralized communities where other emotions come into play,” explains Lia.

The exchange with Xvet was a political act of writing that Lia describes as “two realities converging: a trans woman and an indigenous woman.”

Transpedagogy of Affects

This isn't Lia's first time working with children. She has worked with the Trans Families Network, as well as in public schools and at children's and young adult literature festivals. For her, working with children is "a process of infiltration, because trans people make people uncomfortable in front of a group."

-What is your relationship like with the children you have already shared time with?

-When I'm close to them, I realize that it works really well to embody the story and make it my own. These are precious moments because the little ones also teach me new realities and new ways of healing myself, of radical listening.

With trans and cis children, we must share that caresses, hugs, and kisses are catalysts for moving toward freedom, for moving toward a personal and collective revolution . But it is particularly important to talk about love with trans children because the State has deprived trans people of love .

-Where are trans children in literature and education?

-In Mexican children's literature and the education system, trans people are underrepresented and of little interest; there's little interest in a trans person teaching. When we do appear, it's through a generalized idea of children who decide to feminize themselves, and that's it. There are few stories about trans classmates.

That's why it's so important to me that in Childhood Fighting the Virus there are representations of femininity, masculinity and non-binary identity, but also of ancestors, the elements (fire, earth, water, air) and the almost extensions of identity that face masks, antibacterial gel, and face shields have become... who would have imagined that to survive you have to put transparency on your face?

-What future plans do you have with your writing?

-In 2019, Canuto Roldán and I launched an archive of children's and young adult literature called Archiva Trans Mariquita. There, we gathered materials that address themes of dissent, child abuse, migration, grief, and anti-racism. We currently have around 500 copies. Our vision is for it to become a physical space for radical listening, promoting reading, hosting poetry slams, and a reading room where trans children and adults can find these stories, see themselves reflected in them, and heal.

*The stories in Childhood Fighting the Virus are freely accessible and can be viewed free of charge at this link.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.