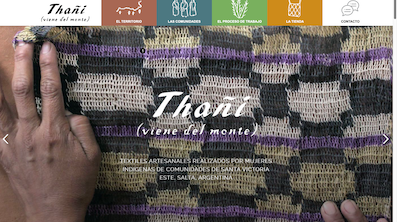

Wichí weavers open a fair trade online store for their handicrafts

Through the collective brand Thañí, which in Wichí can be translated as "Comes from the mountain", indigenous women from the communities of Santa Victoria Este (Salta) sell their handcrafted textiles on the internet and within the framework of fair trade.

Share

By Elena Corvalán. Photos: Fabiola Benítez and Facebook Thañí

They gather to observe the tapestry woven from chaguar fiber. They point out details in its colorful weave and make comments in hushed tones, in Wichí. Theirs are expert eyes. These women came from their communities scattered throughout the forest in the tri-border area of Argentina, Bolivia, and Paraguay, along the banks of the Pilcomayo River, to participate in the first meeting of the weaving groups in Santa Victoria Este. There, the collective brand Thañí , which in Wichí can be translated as "Comes from the Forest," is taking shape. It is the tool they envisioned and worked on for a long time to sell their creations at fair prices, in partnership with various institutions and support networks. It took time, and finally, on April 6, months after that meeting, they opened their online store . There, the Indigenous women from the communities of Santa Victoria Este (600 kilometers from Salta) sell their handcrafted textiles online, within the framework of fair trade.

The women of the indigenous communities who inhabit this area of northern Salta primarily weave textile containers using natural fibers and dyes. But they create more than just useful items: “Each of our pieces is unique, one-of-a-kind, handmade under the shade of the trees, near the fire we cook with. Every geometric figure we create has a meaning, an ancestral message; it carries within it stories of our culture,” they explain in the text presenting their collective brand.

The weavers' groups are from eight or nine communities, but they are united by the collective brand, an initiative of INTA that is financed through the Forests and Community Project of the Ministry of Environment of the Nation.

At the meeting attended by this reporter and Fabiola Benítez, a Chorote community communicator and local resident, the elders are absent. The young women point out that the master weavers have remained in their communities for various reasons. Their names will be mentioned at the gathering in the home of Cecilia Thomas, a member of the INTA (National Institute of Agricultural Technology) territorial team.

The project was unique in that the training sessions were held in each of the weavers' communities, distributed among family groups in La Nueva Curvita, La Puntana, and Alto La Sierra. A total of 127 women received training in innovation, production, and marketing of their work.

Although they only recently launched their online store, the brand has been developing for four years. However, all the groups of knitters had never before come together in a single meeting. They did so for the first time in November 2020 in Santa Victoria Este.

Many of them wear pants or leggings instead of the traditional multicolored skirts. The change is mainly due to their arrival on motorcycles, the new mode of transportation in these parts. Many were brought by their husbands or other male relatives. But some have come alone—quite a change.

The gathering began with introductions, using the technique of spinning a ball of yarn to create a woven fabric as the participants shared their identities. With pauses, some spoke in Spanish and others in their indigenous language. “We are Wichí women from the communities of the municipality of Santa Victoria Este. We weave with chaguar fiber, which we spin by hand and dye with natural dyes. Chaguar is a wild, natural fiber that we gather in the forest, very near the Pilcomayo River,” the women explained in the official presentation of Thañí.

“For a long time we have made textiles for fishing nets and for the bags we use to hunt and gather in the forest. The geometric designs we create are abstractions of fragments of animals from the forest, or of the vegetation that surrounds us. Currently we are experimenting with new designs, combining our ancestral textiles with new materials and techniques.”

At 25, Anabel Luna is one of the first members of the knitting group. She stands out for her wit and her ability to quickly forge connections between groups. “I’m starting to learn many things from my family, from my colleagues, from Andrea, and I’m progressing little by little,” she says.

Hers is a family of weavers. “The whole family is involved: my aunt, my sister, my mother, my grandmother,” and “I learn from them.” For Anabel, the collective branding process is also a learning experience, bringing “new things that one has never seen before,” and it is “important” for acquiring new knowledge, as a sales tool.

According to the weavers, weaving facilitates intergenerational dialogue. Teenagers who had drifted away from ancestral customs are drawn to this practice and restart this exchange with their elders.

The message that traveled to Berlin

The Thañi brand has been quietly and beautifully growing, radiating a need to re-examine the concepts of craftsmanship and art. They have already been invited to participate in exhibitions in the city of Salta, at the Néstor Kirchner Cultural Center in Buenos Aires, and also in Berlin, Germany. There, their works were part of the exhibition “Listening and the Winds” at IFA-Galerie, the art gallery of the German Foreign Office.

The exhibition in Berlin brought together groups of artisans/artists, activists, and communicators from Indigenous communities in the Chaco region of Salta province. It was curated by cultural manager, visual artist, and INTA field worker Andrea Fernández. The exhibition ran until the end of January. The women expressed surprise that their ancient art of weaving with chaguar fiber was appreciated in such a remote place as Europe.

The weavers had requested that the collection of works taken to Berlin be called “silat,” which can be translated as message or warning. And in this case, “it’s like a message for all those who don’t know us. Or don’t know that there are Wichí indigenous women who work in crafts, and that there always have been, since our ancestors,” in the words of Claudia Alarcón.

Andrea Fernández was one of those who traveled through these communities with the exchange workshops. There, the idea of a collective brand was developed as a way to unite and improve the sales conditions for their textile production.

Virtual platforms can help bridge distances. But in the Salta region of the Chaco, in addition to the poor dirt roads, access to new information and communication technologies is also scarce. Therefore, one of the concerns of the INTA (National Institute of Agricultural Technology) workers who support the weavers was to obtain equipment so that the Indigenous women could manage the online store. Thus, at the insistence of the outreach technicians, the National Communications Agency (ENACOM) donated 16 tablets to the weaving groups, which were delivered in December 2020.

Chaguar using the grandmothers' technique

The chaguar plant is found throughout the semi-arid Chaco region, and the Wichí people have used its fibers since time immemorial. But not just any chaguar plant will do. “(The fiber) comes from a specific mother plant. It's carefully selected; it can't have any insects or anything like that, because that cuts the fiber and makes it defective.” That's why “you have to go searching. It's not 2 kilometers away, but more than 50 kilometers from the community,” explained Julieta Ofelia Pérez, a young weaver from Alto La Sierra.

The chaguar plants “grow in the forest, and you have to go deep” to find them. Now, the gatherers travel by motorcycle, even if only to the outskirts, before continuing on foot. Sometimes, “they walk, leaving at 6:00 a.m. to meet with the women who know which plants might be useful.” They harvest the chaguar leaves, then “remove the thorns, then crush and dry them to obtain the fibers, and finally, the threads.”

To obtain the thread, the women join two or three thin fibers and twist them around their legs. Dyeing requires another excursion. “You have to go far into the mountains to find the natural dyes. You have to learn about guayacán, a whole bunch of plants; that's where you get the orange, the black. Sometimes you use the bark, sometimes the roots, the leaves. It depends on what color you want. For example, black is obtained from carob resin,” with guayacán seeds. “By mixing them, you also get an intense black. And there are other plants whose roots yield red, and so on. The same goes for orange, but you have to know the plants well. And that's all what the grandmothers taught us.”

The process can be seen here: Chaguar Hilo .

Then comes the weaving. “It depends on what they ask for,” it will be woven pieces or yicas (handbags, which have a specific stitch made with a needle, the yica stitch). Different stitches will be used, the newest ones and also the old stitch that the grandmothers preserved and are now using again. There will be those who make garments with crochet, a “faster” “invention.” Even with this addition, “it takes about two weeks to make a garment” (see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bpl1vYN54vs&feature=youtu.be , and also https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hr3iBBWn044&feature=youtu.be ).

Weaving as memory and freedom

In Julieta's family, her mother and sister also work with chaguar fiber. Weaving holds fundamental importance in the cosmogony of the Wichí people and other Indigenous communities. In ancestral practice, each girl learned to weave with her first menstruation. This was the case for Julieta; she learned to weave on a loom at age 12 from her grandmother and aunt. Although she later stopped to focus on her studies, she has now returned to the craft.

Julieta recalled to Presentes that she mainly learned to knit “with the other girls, playing when I was younger.” Like other knitters, she also remembered that selling their work was difficult. They needed to keep up with the times. “Things were becoming more modern, the designs were changing, and we had to adapt to customer requests in order to sell.” For Julieta, Andrea’s help was invaluable in that process, as was the help of other “people from outside the community” who assisted with sales.

Julieta is one of the most extroverted. In the meeting led by Andrea Fernández, Cecilia Thomas, and Julia Ridilinier (also from the INTA team), there are pauses, silences, meaningful glances, and group consultations unusual for the white world.

Andrea Fernández believes that society must "give a place to that production, to that memory," so that it not only has a place in squares and fairs, but also, in addition to occupying those spaces, "can be recognized, valued, legitimized, if that word is appropriate, as an artistic creation, as something that is done from freedom. Women choose to do it."

Indigenous territory

Santa Victoria Este is the main municipality of the extensive Rivadavia department. The majority of its population is Indigenous, primarily from the Wichí people. There are also residents from the Chorote, Tapiete, Chulupí, Guaraní, and Qom peoples. Starting in 1902, people of mixed Indigenous and European descent (criollos) began arriving in this territory, becoming known as Chacoños. Encouraged by public policies, they settled under false pretenses, and since then, a territorial dispute has persisted. This dispute should be resolved by complying with the ruling of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR), which last February ordered the Argentine State to grant communal land titles to the Indigenous communities and relocate the criollos (see here: https://www.corteidh.or.cr/docs/casos/articulos/seriec_400_esp.pdf).

This region, with its harsh climate, is traversed by two large lowland rivers, the Bermejo and the Pilcomayo. Both originate in Bolivia and are fed by the heavy summer rains, which sometimes cause them to overflow. The cycle repeats itself every year: floods in the summers and droughts in the winters.

This is also a land of mountains and their bounty, from which the original inhabitants lived, and still live in part today, although with increasing difficulty due to deforestation and agricultural activities. In this context, the weavers practice their art, rescuing the knowledge, uses, and practices of their ancestors, and trying to incorporate new knowledge to sell their creations.

From cholera to the coronavirus pandemic

In early March 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic reached the country, mentioning coronavirus in Santa Victoria Este was almost like speaking nonsense. However, when news from abroad materialized into concrete measures, many people associated the new plague with the one that afflicted the area in the 1990s: cholera.

Between 1992 and 1993, there were 2,633 cases of cholera and 49 deaths, the vast majority among Indigenous people from Salta and Jujuy. Many of these people were from Santa Victoria Este and its surrounding area. The devastation of cholera left its mark. So profound that when news of the coronavirus arrived, it brought those same painful memories back into the present.

Santa Victoria East

Lying on the banks of the Pilcomayo River, Santa Victoria Este was in the eye of the storm during those years, with the plague following the course of the water, which originates in Bolivia and flows down, bathing towns like Crevaux and Villa Montes, crosses the international border, and continues separating Bolivian and Argentine settlements. On this side, it wets La Puntana and continues its journey bordering Santa Victoria Este and the other small towns that have sprung up under its influence, until Misión La Paz, which faces Paraguay, on this side of the international bridge.

At that tri-border area, the arrival of the new white plague stirred up memories of cholera. The residents of Victoria went from disbelief and indifference to concern. Aware of the state's shortcomings in these places, they organized themselves to ensure compliance with preventative health regulations. Thus, self-managed checkpoints were established at the entrances to Santa Victoria Este, Misión La Paz, Santa María, and many other communities in the area. But after that initial shock, things slowly returned to normal.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.