The pandemic as told from the perspective of La Voz Indígena, a community radio station run by women

La Voz Indígena broadcasts from northern Salta, Argentina. It began as a project in a workshop for women focused on ethnic memory. It has been on the air for 12 years, and its role was crucial during the pandemic.

Share

By Elena Corvalán from Tartagal (Salta). Photos: Mariana Ortega and La Voz Indígena archive

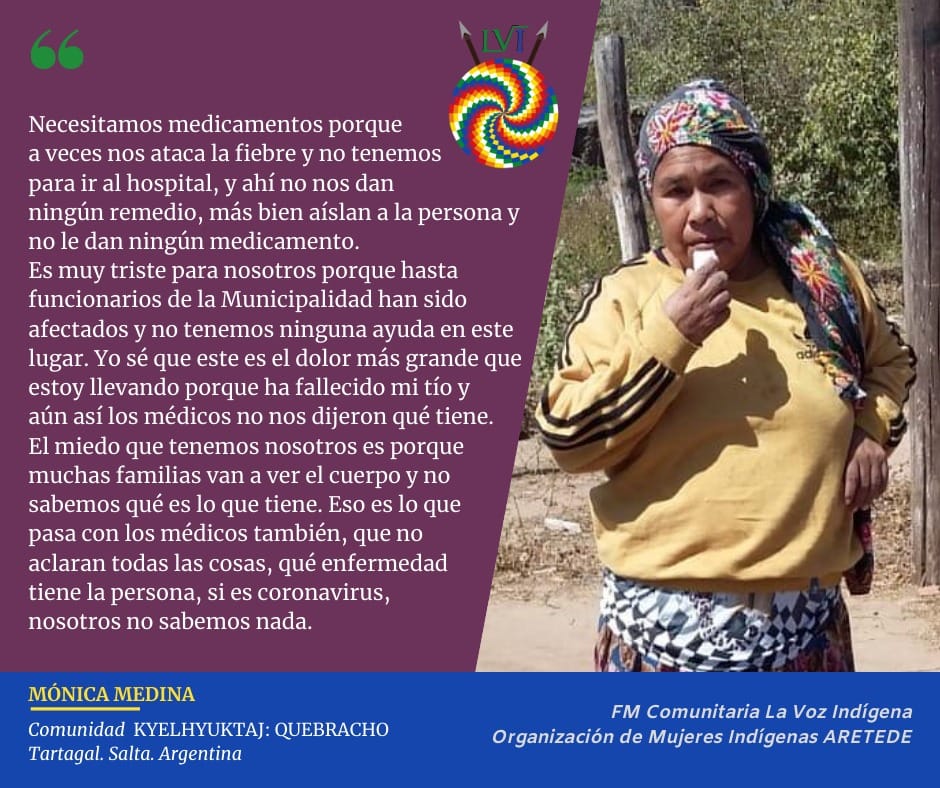

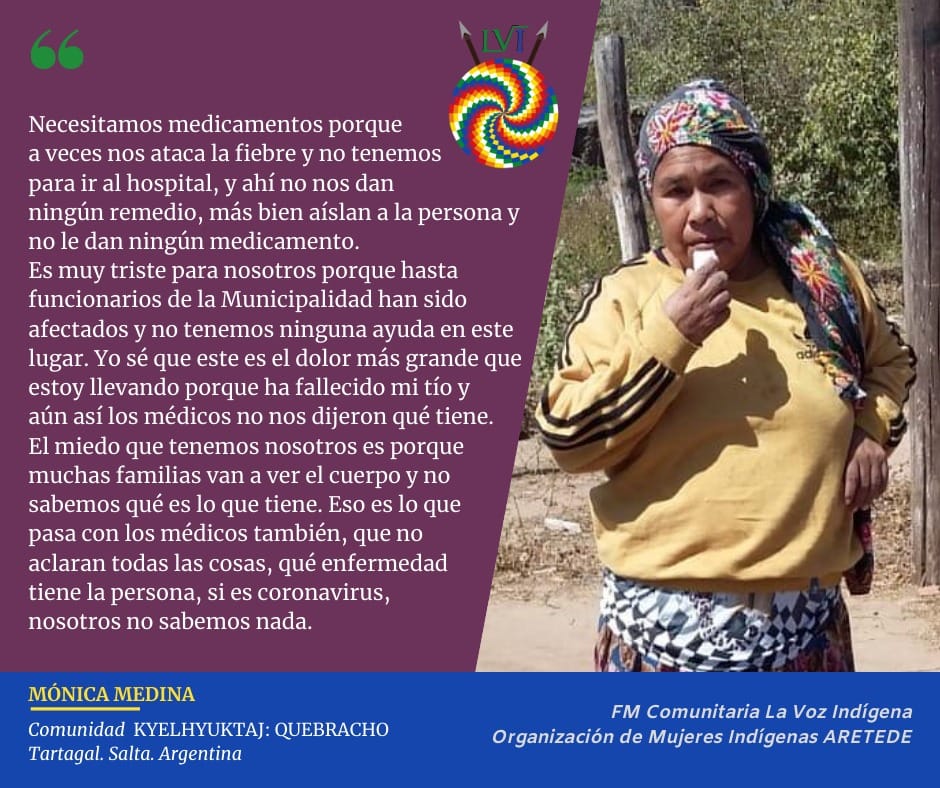

Felisa Mendoza is about to turn 72 and is one of the directors of La Voz Indígena (The Indigenous Voice ), the first radio station run by Indigenous peoples in Argentina. It broadcasts from Tartagal, in the north of Salta province, on FM 94.5 MHz . “ We are an Indigenous organization, founded and run by Indigenous women,” its members explain. And although Felisa never uses the word “feminism” during the conversation, her work and that of the women involved in this media outlet is framed within the struggle for a society free from oppression and with rights for all. They carry this out in the field of communication, but also far beyond. In this context, the radio station is also a refuge. During the coronavirus pandemic, La Voz Indígena served as a crucial space, responding to the community from different angles, even amidst the difficulties.

Community radio was concerned with disseminating knowledge of its ancestral medicine, but also with finding food and supporting communities harassed by the advance of business on their territories.

La Voz Indígena has three directors. Nancy López is one of them. A communicator, niyat (chief) of the O Ka Pukie Community, and a prominent advocate for the rights of her people, she presented the abuses suffered by Indigenous communities in the region to the UN in 2019. Nancy examines her past and present through a feminist lens. And there were other historical figures like Lidia Maraz, who are no longer with us.

“ Our collective brings together people from the different Indigenous communities that live in the area.” They know that it doesn’t matter which community they belong to: they can talk about the process of self-recognition of the suffering they endure for being women. And also about recovering the historical memory of their communities. These are the major themes addressed in La Voz Indígena (The Indigenous Voice): gender violence, women’s rights, the connection to the land, agriculture, language, gender nonconformity, and the trans population.

How memory became radio

The radio station began its first broadcasts on October 11, 2008, but its origins had been in the works for much longer. Its beginnings can be traced back to initiatives such as the Ethnic Memory Workshop, which emerged in 1999 at the initiative of anthropologist Leda Kantor.

Felisa recounts that she began working with her “to learn about my rights as an Indigenous woman.” Years ago, the anthropologist settled in Tartagal and joined the demands of the Indigenous peoples. Today, she is considered a sister. “She would visit our communities and invite us to her home. We held the first workshops for women from different ethnic groups, and there we shared our problems. And sometimes we had the same problem.”

Those lessons learned in the Workshop, which they also call the Historical Memory Workshop and which consisted of women's meetings to discuss their rights, were the origin of the radio station. It was conceived as a tool to make visible the discrimination and racism they endured, especially in healthcare . It was a women's project that was later joined by men, particularly young men.

Communication against racism and for rights

Felisa recalls that in 2002, the Ethnic Memory Workshop received a proposal from students at the National University of Salta (UNSa) to offer training in social communication. She signed up. Although there were radio stations in Tartagal, they couldn't go there to raise their issues, such as the discrimination they faced at the Juan Domingo Perón Hospital, where they were made to wait for hours, or the territorial conflicts that pitted them against local business owners.

The workshop was led by university professor Liliana Lizondo and trans communicator Casandra Sand , a member, along with them and Leda Kantor, of the Aretede Foundation, the organization they used to advance their project of creating their own radio station. As part of the workshop, the communities secured an hour on Saturdays at Radio Nacional Tartagal to broadcast a program. “They gave us airtime from 12 until 1, but we had to arrive, and once the hour was up, we had to leave.”

Sometimes there were so many problems that they didn't have enough time to talk about them. They had to wait a week before they could go on air again. Seven communities participated and had to take turns hosting the program. "I used to tell Leda, 'How I wish we had our own radio station!'" recalls María Miranda.

Leda looked for a place to study. “The radio station was tiny. But we already had what was ours. We could finally leave with the peace of mind that came from not being rushed.” Then, “each of us brought the problems of our respective communities.” The long waits at the hospital were a recurring topic of conversation. “We, as Indigenous women, are very quiet; we don't make demands. We sometimes come to the hospital with our sick children, or to start a family. We don't demand to be seen quickly; sometimes we are so patient that we wait until they finish attending to the other patients, and then we are last .

“All of that bothered me. Why? We are all human beings, and we as women also have the right to be treated well. And for that reason, we have our radio station,” Felisa explains.

“Nobody knew if there was malnutrition” in the communities, “but with this radio station, the people are now a little more aware,” says Felisa. And she believes something similar happened with the poor care at the hospital. “Before, it wasn’t known; it was as if everything was fine. The discrimination still exists, but not as much as before. As an Indigenous person, we were never treated the way we should be.”

Radio during the pandemic

The preventative isolation measures implemented due to Covid-19 impacted La Voz Indígena (The Indigenous Voice). The quarantine meant that their broadcasts ceased for a time. Some of its creators lived in remote communities, in Yariguarenda or Kilometer 6, and had no means of transportation to get there. Broadcasting from their homes was out of the question, because the vast majority of these communities have precarious digital connectivity. There is also no good cell phone signal; in fact, the communities located along National Route 86 don't even have electricity.

Furthermore, other priorities emerged, as indicated by technician Sebastián Gómez in the National Report “Socioeconomic and cultural effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and mandatory preventive social isolation in the Indigenous Peoples of the country” published in June 2020. The Aretede organization “since the pandemic was declared has focused primarily on obtaining and distributing food through the networks of the popular economy.

The radio station delivered supplies and hygiene products. But the women say there was another major problem to face: assisting and supporting communities that, in the midst of the pandemic, had to confront pressure from landowners and businesspeople trying to encroach on their lands. And the organization was there, above all.

Prevention campaign in indigenous languages

As soon as it was able to resume its activities, in May or July of 2020, the Indigenous Voice broadcast public service announcements in native languages about measures to prevent the spread of the coronavirus. It also carried out a communication campaign, using posters and audio recordings, sharing knowledge and wisdom about traditional medicine .

“This is how we’ve fought this pandemic, with traditional remedies,” says María Miranda. María is Felisa’s daughter and works at the radio station. She says that in the last year there’s been a return to the remedies the forest offers, even now, despite the deforestation . They’re using eucalyptus, lemon, and matico, which is boiled and consumed like water. “The eucalyptus was used for steam inhalation, and the lemon was used to soothe sore throats and chest pains.”

Felisa recalls that at the height of the pandemic last winter, people “were afraid to come to the hospital because they would be admitted and die the next day.” And María says, “Going to the butcher shop was already a hassle, so people were afraid, and they asked what could cure them.”

A refuge for those who come from afar

Whenever they are invited to speak about their experience with community radio, the directors emphasize the growing awareness of the similar problems women face, regardless of their community. They also highlight the solidarity that has led the radio station to also serve as a meeting place for Indigenous people from all over the Salta Chaco region who travel to Tartagal to complete paperwork and access healthcare.

Tartagal is the most important city in the far north of Salta province. Its hospital is the most advanced in the region. Residents living more than 200 kilometers away, sometimes traveling on very difficult stretches of dirt road, are referred for treatment in this city. This presents a significant problem for people with very limited financial resources, and even more so given that it is customary for the indigenous people of Chaco to have the entire family accompany the sick person. Families manage as best they can to reach the city, where they often have no relatives or acquaintances, nor the money to pay for a hotel.

It was in this context that La Voz Indígena (The Indigenous Voice) emerged. María Miranda, from the 9 de Julio Community, described the radio station “as a refuge for people who come from farther away ,” without family in the city. They are welcomed “so they can stay the night, make some tea. We have a small kitchen, there’s a bathroom, so they spend the night and then come to the hospital. They come from Chaco, they come from Alto La Sierra (located on the tri-border area with Paraguay and Bolivia, 226 kilometers from Tartagal). And here we have a small room where we have at least a bunk bed, we have mattresses, they stay there because they have nowhere else to go.”

The radio team members pool their money “to buy bread and sugar” to offer them. “So for our people, this is a refuge where they can come and stay peacefully without paying anything because they come from far away. Sometimes they have very little money, not even enough to eat. And we here, as members of the committee, do our part” to help them. “Sometimes they don’t even have bus fare to get back home.”

“We all have the same problem”

María emphasizes that this idea arose from the observation that “ all women from all communities, all of us, have the same problem ,” referring to the “discrimination” faced by Indigenous peoples. “We thought of it because we saw so many people suffering in the hospital, sleeping outside.” María also highlights that the initiative was started by women, and later “the guys” joined in; young people, in particular, became interested.

One of these young women is Edith Martearena, a communicator from the Tejé Community, a member of Aretede, and a technician in Indigenous Community Development. “We, as a women's organization, have also been providing support to communities regarding their access to land and territory.” “That's why the radio station has become a meeting point for community leaders .” “Besides, we're the only media outlet, for example, that will listen if someone comes to denounce a landowner. We won't shut down the microphones, unlike what they might do in other spaces.”

The women of the radio station believe that "the legal aspect is beyond our reach," a crucial issue for dealing with the criminal proceedings and civil lawsuits filed against them by landowners with whom they are disputing land rights. For a year, with external funding, they have had the assistance of a non-Indigenous lawyer, but that contract is now ending. They lament the lack of lawyers in their communities. In this region of Northwest Argentina, law degrees are only offered at the private Catholic University of Salta (Ucasal), a significant obstacle due to the high tuition fees, making it unaffordable.

One of María Miranda's five daughters attended the Catholic University until her third year, but her scholarship from the Provincial Institute of Indigenous Peoples of Salta (IPPIS) ran out, and she had to drop out. Now she's studying for a Technical Degree in Indigenous Development at the Campinta Guazú Intercultural Higher Institute in Jujuy. She'd like to finish her law degree, but she doesn't have the financial resources. Edith, who graduated from that Technical Degree program, says, "Like her, there are a lot of kids who aspire to continue studying, but we don't have the means to send them, to start helping them because, well, here we live day to day."

Right to speak

La Voz Indígena (The Indigenous Voice) broadcasts Monday through Friday, from 9 a.m. to 6 p.m., with “a varied program schedule, mostly news-based in the mornings, three times a week.” There are programs from different communities. “In the afternoon we also have programs in Wichí, and also a collaboration between a Wichí and a Toba couple, who work together,” explains broadcaster Edith Martearena. “And on Wednesdays and Fridays we have a program from a school, Cacique Cambaí. They also come on for an hour to contribute their learning through radio from home. Other teachers from Kilómetro 6 have put together a short program and broadcast it at midday.”

María Miranda highlights Leda Kantor's initiative in driving this project forward: “She helped open our minds, showing us that we as women have the right to speak out and express our feelings and thoughts. Because before, there was a lot of gender-based violence, and women kept quiet. They didn't talk about what was happening in the community, perhaps out of fear or shame.”

“Before, we were the ones who stayed at home. The man was the one who went out into the street to find food and all that.” And when Leda went to the community to talk to them, to question those mandates, “that’s how women started to come together everywhere.”

Leda's words brought about a radical change in María's mother, Felisa Mendoza. "My mother was never home anymore," the daughter recounts, laughing. This caused conflicts in her marriage: "My father was getting older, and my mother would tell him, 'I have to go to the meeting.' And she would leave, for two or three days, going to Buenos Aires, to Catamarca, wherever the meetings were. She would go with the problems that our communities have, the evictions from our land, how they keep taking our land away."

At that time, Felisa's youngest of five children was five years old. “My husband sometimes told me I was neglecting my children. I would tell him, ' I'm going to learn more. We, as Indigenous people, as women, face so much discrimination. I want to know my rights .' And so, talking, I would convince him to go out again. “But when I went for longer periods, he didn't like it at all anymore. Sometimes I would go for a week.” Felisa explains: “I was determined.”

And Mary began to walk too

Then Felisa started inviting María, who was married, to the gatherings. “And he (her husband) tells me, ‘Now you’re going to make her fight with your son-in-law; he’s not going to like her going out.’” “And around that time, María started dating too.”.

With eight children, she didn't travel as much as her mother, but she began to participate in the meetings. Her husband sometimes questioned her. She would reply, " In the future, maybe one of my children will follow in my footsteps. They need to know our rights as women, how to defend themselves, because you know, at the hospital they don't treat us quickly; they make us wait a long time because we're from Indigenous communities. We're all equal, no one is better than anyone else ." And then he would say, " Okay ."

María followed her mother “after so many years of walking. Because she’s been walking for over 20 years, and I’ve only been walking for about ten or twelve years. I’m just now keeping up with her, so I can work and support her.” “It’s hard to leave the house,” she reflects.

Although many women initially attended the Ethnic Memory Workshop, María recalls that several left. Only representatives from the Guarani, Toba, and Wichí communities remained. “As women, it’s always difficult for us, I say. Perhaps the other women also had the same problems with their husbands,” she reasons. She emphasizes the women’s persistence: “If we hadn’t continued with this,” they wouldn’t have the radio station.

Women's meetings, the seed of radio

Nancy López contextualizes those first meetings. “It was difficult. In '99 there were no female chiefs, no female representatives .” So, “when we said it was a women's meeting , the men would say, ' Well, no. But this is new for us .' It was as if they saw that we didn't want the men to participate.”

“Why women? Because in the beginning, we shared our experiences, and it was very important that only women be present. There were many women who had suffered, others who had fought in the Bolivian-Paraguayan war and had very harrowing stories. They recounted how they had suffered, how they had been imprisoned. Some had been raped during the war.” Like the case of a woman who “had two young daughters, so to keep them from being taken, she offered herself up for their sake. These kinds of things came out of those women's meetings.” They unburdened themselves. “They released all the weight they had been carrying for 40 or 50 years.” In those meetings, many recounted being raped by their own relatives, “right there in the house.”

“We are beginning to understand that we have rights as women. No one can come and touch my body if I don't want them to. No one can force me.”

Nancy says she hasn't had personal experiences of gender-based violence, but "listening to many women, sometimes older women, carrying all these burdens, I realized that when a woman is always quiet, doesn't talk, doesn't laugh much, doesn't play, doesn't joke around, that woman has been carrying something for many years. She is suffering ."

Then she began her own activism, trying to help abused women. She would visit them, “asking them how they are. Sometimes they tell me, 'I'm fine,' but when they see their husband arrive, they change. That smile disappears, they lower their face,” and “even though they tell me they're fine, I know they're not.”

Nancy affirms that those meetings were healing for many women. Experiences that were both “beautiful” and “painful.” “Because I saw a mother crying, letting it all out in those meetings, and they left feeling free, eager to continue talking. And one woman said, ‘ Well, then I can get ahead on my own, without a man ,’ because the prevailing thought was that without a man I couldn’t do anything. That’s what we’re taught out there too, that without a partner you can’t do anything because you’re a woman.”

Nancy says that realization was fundamental for many. That a woman could realize that “without her partner, who was a violent man, she could move forward. “Then you start achieving many things, and they are good things, because sometimes we as women from indigenous communities are the ones who remain silent, we always keep quiet about everything that happens to us, everything we suffer, everything we carry,” in “a total silence about everything.”

Books for memory and identity

Leda Kantor, they say, also encouraged them to recover the stories of their communities, so they wouldn't be lost. "And so we each went out in our own communities to gather these stories," says Felisa. They visited the elders in each community and asked them to share their memories. Sometimes they had to go two or three times because, generally, they didn't want to talk. "They didn't want to tell the story; it was painful to remember what they went through in the war between Bolivia and Paraguay. Many people came to Argentina during that time," explains María.

The women remembered “an old woman who is no longer with us. She would cry as she told that story from when she was about ten or twelve years old. Remembering what had happened in her life was very sad.” That story, and others, were recorded in the books the women made and edited with the intention of preserving the memory for “young people who want to know how Indigenous peoples lived in their time.”

The first, “Moon, Tigers, and Eclipses,” was published in 2003. The second, “The Birds’ Announcement,” in 2005. They expect to publish three more soon. The coronavirus lockdown was one of the reasons that led the women of the radio station to resume their exchange at the Ethnic Memory Workshop. Now they are working on a series of books soon to be published. “Knowledge, memories, and stories that narrate the historical struggles of the Indigenous peoples of northern Salta” is another crucial dimension of the work carried out by La Voz Indígena (The Indigenous Voice). “ We are an active part of the history of our peoples and we fight for our territory, the right to communication, ethnic memory, gender equality, and, fundamentally, for our Indigenous identity .”

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.