Mapuche women, ancestral medicine and their collective response to the pandemic

Ancient medicine seeks to heal our mind and body, but above all, our spirit.

Share

By Carina Fernández

Illustrations: Celeste Vientos

When the coronavirus pandemic began to impact Argentina, Indigenous nations were not consulted in the development of a health protocol that differed from that of the rest of the population. The characteristics of each territory and of rural life were not taken into account. The mandatory quarantine resulted, in many cases, in a decline in family economies; people were unable to return home for months—stranded in other provinces—and faced institutional violence from both the police and the medical system.

According to complaints from indigenous organizations and academic research, this was aggravated by the lack of access to public health and the lack of connectivity to access circulation permits and applications proposed by provincial governments.

The pandemic brought into focus not only access to health for these historically exploited and exterminated nations, but also opened up the debate – internally but also from international organizations such as the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights – about the need to integrate and respect ancestral native medicines.

From diverse Indigenous worldviews, spirituality permeates all aspects of life. These are ancient wisdoms that help us understand the relationship between everything we see and everything we don't see. According to this worldview, we are connected to our ancestors; to the forces of nature that make possible the existence of mountains, rivers, animals, and all living things. Ancestral medicine seeks to heal our mind and body, but above all, our spirit.

Presentes interviewed Mapuche women who are part of the Indigenous Women's Movement for Good Living (MMIPBV), who, from the south of the plurinational territories that make up the Argentine soil, gave us their reflections, rakiduam, regarding how they went through this pandemic 2020 and how access to health was for them in the province of Chubut, where they live.

“A complete lack of health protection”

“We lack many doctors, especially for us as indigenous people. The local people are more protected because we live in an area and a province where everything is very turbulent,” says Marilin Cañio, werken -spokesperson- of the Lof Cañio Pangui Wingkul (fifth generation of the Cañio community in Cerro León) of El Maitén, Cushamen department, in the north of the Chubut province.

Chubut is a province with a heavy presence of security forces, in addition to the private guards hired by large landowners. This creates an environment of control and criminalization of a population fighting for territorial recovery and the defense of life against extractive projects. This state control has an inseparable impact on the bodies and territories of Indigenous women, and the pandemic brought these structures to light. The pu lof ) are part of the anti-mining assemblies defending water.

“The pandemic caused a complete lack of health protection, which was already being violated due to the lack of budget in the province of Chubut and the lack of healthcare. But now that vulnerability has been much more aggravated,” says Moira Millán, a Mapuche writer and weychafe (defender) , activist for human rights and Mother Earth.

“In most communities, COVID-19 hasn't yet entered. This is also related to the eating habits in rural areas. People there stay more active because there's a lot of work to do in the fields. You have to get up very early, take the animals out, collect water, go out to gather firewood, and during harvest time you have to go out and harvest, gathering all the food for the winter. I think that also helps maintain, let's say, optimal mental health, because you're busy,” says Juana Antieco, a licensed nurse, member of the Indigenous Women's Movement for Good Living, the Plurinational Transfeminist Multisectoral of Rawson, and the Ni Una Menos Chubut collective.

The importance of ancestral medicine

The International Labour Organization (ILO) Convention 169 on “Indigenous and Tribal Peoples in Independent Countries” in section V “Social Security and Health” (Art. 25.2) states that “health services shall, as far as possible, be organized at the community level. These services shall be planned and administered in cooperation with the peoples concerned and shall take into account their economic, geographical, social and cultural conditions, as well as their methods of prevention, healing practices and traditional medicines.”

The health crisis caused by Covid-19 generated a widespread lack of attention for several areas of health, further increasing the difficulty in accessing public health for a large part of the population.

“One day when my daughter wasn’t feeling well, we went to the clinic where she usually saw her family doctor. But the clinic was focused solely on treating COVID-19 cases, so they weren’t attending to other types of illnesses . We had to go to other places, and even at the regional hospital, we couldn’t get tests done because they were operating at reduced capacity and weren’t covering all the tests we needed. Luckily, we found out that Machi Mawün in Esquel, and we were able to see her. The Machi was able to treat not only my daughter but the whole family, and this is very important because we understand that health is also connected to the spiritual. So, in addition to giving us lawen —Mapuche ancestral medicine: a mixture of herbs and medicinal plants— and telling us how to carry out the treatment, she also helped us a lot with our spirituality,” Evis Millán, a Mapuche artisan and teacher, told Presentes.

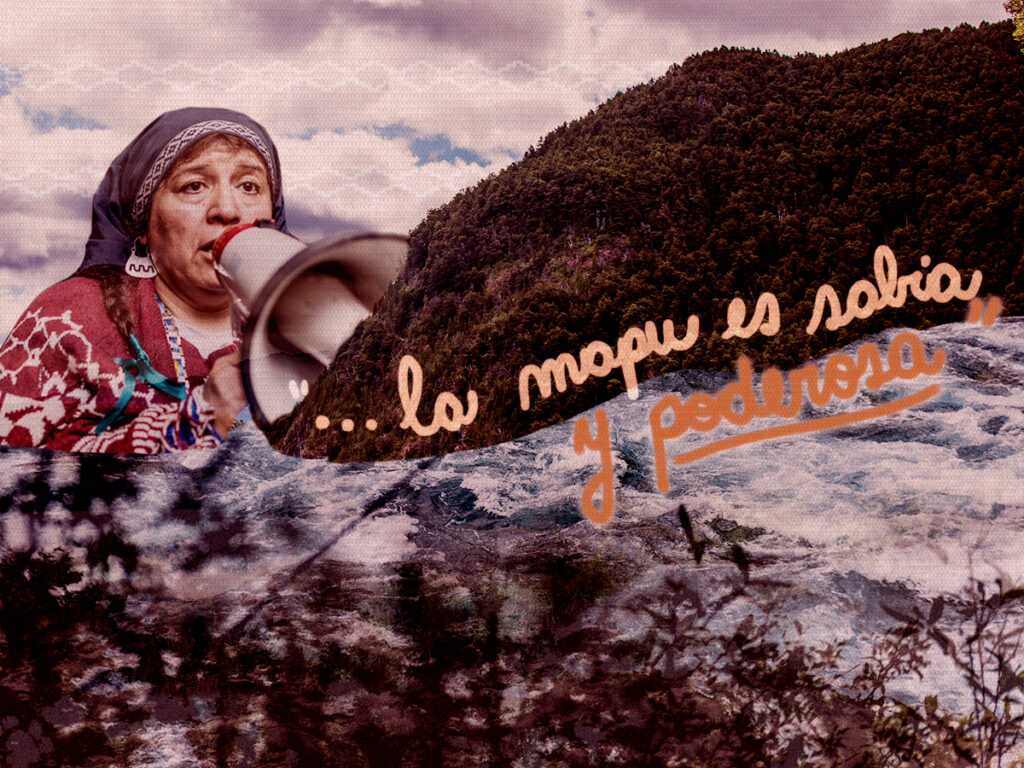

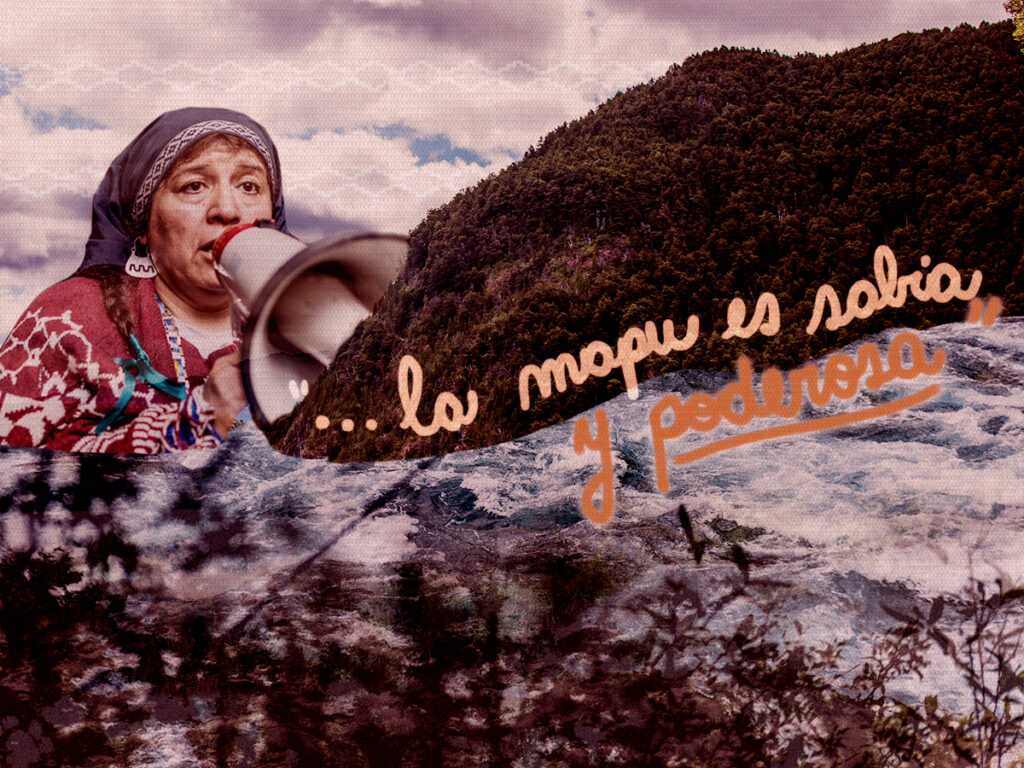

To be a Machi is to be a spiritual authority of the Mapuche people. The Machis heal, using natural herbs, both physically and spiritually, Indigenous and non-Indigenous people who choose to be treated with ancestral Mapuche medicine. Their newen – spiritual strength – is inherited from an ancestor; it is a family legacy. The role they play is fundamental in the collective life of the Mapuche people, as the Machis represent the connection between people and the spiritual and physical energies or forces of the Mapu – the land.

The Mapuche people are historically transboundary, as they predate the formation of the nation-states of Chile and Argentina. They have always moved across both sides of the Andes Mountains, a territory known as Wallmapu. Generally, they cross through land border crossings, which were closed before the airports, in March 2020. Thus, Machi (spiritual authority) Mawün Jones, who lives in Temuco in Gulumapu (Chile), was on the Puelmapu (Argentina) side attending to her patients from the Esquel area when the borders closed. She was stranded, unable to be understood in her own identity.

During quarantine, the tourist visa that the Machi —an Argentine citizen on paper— used in Chile lost its validity, and her marriage certificate was also not accepted as a supporting document by the authorities.

“All of this demonstrates a colonial state logic that refuses to recognize the physical and spiritual need of Machi Mawün to have constant movement between Gulumapu and Puelmapu,” stated the MMIPBV through the campaign “The Andes are not a border, for the immediate return of Machi Mawün to her rewe. Chi Mawiza Malal Femngelay. Ñi Wiñotun tachi Machi Mawün tañi Rewe mew.” This campaign was launched precisely to bring this case to light and to assist the Machi during her forced stay in Argentina until November 2020.

“The pandemic isn’t over yet, so we can’t talk about a post-pandemic world. Mother Earth is wise and powerful, so she provides us with everything we need to live a healthy life, if we so choose. Knowledge of ancestral medicine has also played a significant role in navigating this pandemic, because we were able to start sharing the ancestral medicine that a lamien— brother — or an ñaña— elder—had taken, and cleanse ourselves with it. We began to take better care of ourselves, to eat better, especially those of us who live in the city, and this strengthens our immune systems,” says Juana Antieco.

This article was produced with the support of the Embassy of Canada in Argentina.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.