Paraguay's law on community kitchens does not benefit indigenous women

With Covid-19, the food emergency worsened and state institutions did not provide quick responses to alleviate the effects of the lockdown measures.

Share

Text and photos: Concepción Oviedo

Before the pandemic, many Indigenous communities, hundreds of kilometers from the Paraguayan capital, were already eating only once or twice a day. With Covid-19, the food emergency worsened, and state institutions failed to provide swift responses to mitigate the effects of lockdown measures.

On March 11, 2020, the first quarantine was announced, and communities in the eastern and western regions took responsibility and established community agreements. Both the Santa Rosa community of the Qom people (49 km from Asunción, Villa Hayes department) and the Tekojoja community of the Ava Guaraní people complied with the biosecurity measures, staying in their homes as ordered by the government.

“We started holding assemblies in two communities, and the topic was how we were going to survive, how we were going to resist, because we were told that we had to stay isolated, use face masks, and use hand sanitizer. First, we thought about where we could get medicine and alcohol. Because we had already planned to make face masks by hand, but hand sanitizer and rubbing alcohol have to be bought. There was immense concern among those who lived in the community. Also, a leader died; he was afraid because he had a history of tuberculosis,” explains Bernarda Pesoa, a Qom leader from Santa Rosa.

Bernarda is part of the National Coordination of the Organization of Peasant and Indigenous Women (Conamuri), dedicated to the struggle for women's rights, the defense of their territory, and food sovereignty. Her leadership is characterized by attentive listening, and she speaks three languages: Qom, Guarani, and Spanish.

“The disease brought harm; we are going to die without land, from hunger, and many other things that oppress us ,” adds Beatriz Rivarola, an Ava Guaraní leader from the Tekojoja community in the department of Canindeyú, speaking in her native Guarani language. She is also one of the 300 women who founded Conamuri and has spent years fighting for access to decent housing, electricity, and territorial sovereignty.

Beatriz is known for leading protests demanding territorial rights, denouncing the expansion of the agro-export model, and the criminalization of social movements. She also denounces the threat posed by armed civilians to Indigenous communities in her region. The most recent incident occurred in Veraro in 2020, at the height of the pandemic.

Isolation

Anita Barreto, an Ava Guaraní woman, is one of Beatriz's daughters and also lives in the Tekojoja community. She was seven months pregnant when the quarantine began; she couldn't continue her prenatal appointments because the only priority was attending to people with health problems due to Covid. Furthermore, leaving the community was difficult because of the strict control of the military checkpoints. “The day I had my baby, they treated me well, but before that I wasn't taking any medication and I didn't have any checkups, and the soldiers at the entrance mistreated you to make you pass. If you went to the supermarket, they asked for proof of your trip; it was difficult to leave. I was pregnant during the total lockdown. My sister-in-law helped me; I couldn't have done it alone. She has a degree and helped me a lot because she works in Indigenous health.”

The communities of Bernarda and Beatriz, like other Indigenous communities, are very isolated, with no way to sell handicrafts, medicinal plants, or do odd jobs. This meant they had no income for food. To survive, they began asking for donations from allied networks and friends.

The artisans of Santa Rosa were also unable to go out to sell their wares. Their solution was to take photos and offer them via social media. But they encountered difficulties making deliveries. During October, the government mandated the use of electronic cards, a measure that affected the entire country because there weren't enough of them. This created a problem for the population and particularly affected the artisans of Santa Rosa, who had to travel to a fair in the capital to earn money for food. The only shop there, located 2.5 kilometers away, didn't have the cards. They all had to return home; they had the bills and coins to pay for the bus fare, but not the cards.

Solidarity networks

While the State merely repeated the slogan #stayhome through the media, in Santa Rosa as in Tekojoja it was the women who took on the task of obtaining food, given the helplessness of seeing families with nothing to eat.

Bernarda emphasizes that they organized community kitchens to feed the community, especially the elderly, children, and pregnant women. They cooked once a day because that was all they could afford. They used the donations they received to cook.

Community kitchens have sprung up in urban periphery neighborhoods, in city districts of the Central Department, and in rural and indigenous communities. In the face of government absence, they fed thousands of families. The right to food was made possible thanks to solidarity networks created to collect vegetables, oil, noodles or rice, and meat, as well as thanks to a proposed law demanded by civil society organizations.

The state-run soup kitchens that never arrived

The State created two public policies to provide economic assistance to informal workers: Pytyvõ and Ñangareko. Access to these programs required registration on a platform that demanded an internet connection and basic computer skills. This made them difficult for Indigenous communities to access. Furthermore, the government explained that economic assistance for Indigenous communities would be provided through the Tekoporã program , which delivers Gs. 455,000 per family every two months. Within the Santa Rosa and Tekojoja communities, residents report that the assistance arrived only once during the most critical months, emphasizing that those not enrolled in the program were excluded from all social assistance programs during the pandemic.

After several months of solidarity contributions, the allied networks and friendships were exhausted: the economic crisis of the pandemic was affecting the Paraguayan population in general.

The law

At the end of July, a group of senators presented a proposed Law of Support and Assistance to Community Kitchens, as a state response to guarantee food for families who relied on community kitchens throughout the country. It was tacitly approved by the executive branch on September 16. 35 million guaraníes were allocated, to be administered by the National Emergency Secretariat (SEN), the Indigenous Development Institute (INDI), and the Ministry of Social Development (MDS).

This law was created thanks to the struggle of women, civil society organizations and indigenous communities, who demanded basic human rights, health care and food from the State.

This resource is part of the credit line authorized in Article 33 of the State of Emergency Law throughout Paraguay, prioritizing the purchase of products from family farming. The regulations were drawn up by the Directorate of Public Procurement, which explains that it is the responsibility of the contracting authorities to communicate their procedures, as stipulated in Resolution 4272/2020 published on September 28.

An organization that is not accountable

Corruption in the use of public funds from the loan intended for health emergencies was a recurring issue. The National Network for the Right to Food, which includes several organizations and independent soup kitchens, among them Conamuri (an organization of peasant and indigenous women), held a protest with a community meal on September 21. On September 23, they submitted a letter requesting the creation of a working group between the responsible institutions and the beneficiaries.

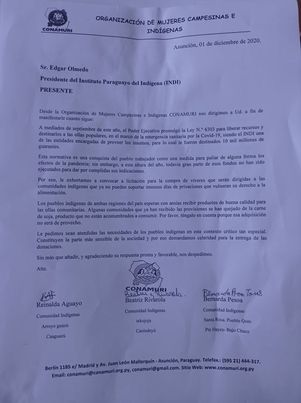

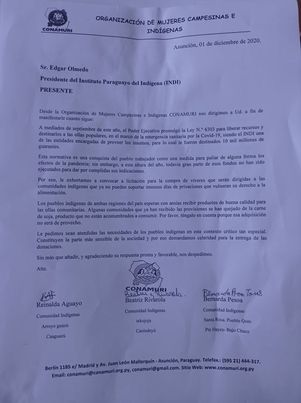

The main objective was to ensure transparency in the use of public funds and prevent them from going to shell companies that profited from public resources. The aim was to control the distribution of products and regulate the purchase of agricultural products from small-scale farmers and meat from local businesses or meatpacking plants. The letter submitted to the National Indigenous Institute (INDI) received no response.

On December 1st, Conamuri again submitted a letter to the INDI (National Indigenous Institute), urging them to hold a public tender for the purchase of high-quality food. This letter also received no response. According to the government's website rindiendocuentas.gov.py , the INDI has spent 9.944 billion guaraníes to date, out of the 10 million allocated. This money did not reach the community of Santa Rosa, which has not received any food kits. The Mbya Guaraní community in the department of Caaguazú is in the same situation .

“We went to the INDI to take our document to the front desk, for the INDI it was very strange, they had no notification about that Law, after all, it does not benefit us,” says Bernarda.

Tekojoja was the only community that received non-perishable food supplies even once. It was enough for them to cook for two weeks . Beatriz emphasized that other Mbya Guaraní and Ava Guaraní communities in the department of Canindeyu also received nothing. “The community kitchen once arrived from Asunción, and we took turns cooking, the women helped each other. There were no vegetables, and the meat was soy meat. It was four five-kilo packages of rice, noodles, soy meat, a liter of canned goods, and four bottles of oil. We absolutely use five kilos to cook in the community; we cook twice a week. There are many of us—58 children, and among the adults, a total of 130 people eat.”

The National Indigenous Institute (INDI) has not provided a detailed accounting of the funds allocated under the Community Kitchens Law. At the end of August, Óscar Vázquez, logistics director, explained to a national media outlet that during the pandemic they delivered 46,000 food kits to 410 Indigenous communities in the Eastern Region.

For those initial deliveries, they had 8 million guaraníes, and with the Community Kitchens Law, they were supposed to manage an additional 10 million guaraníes, which meant they could expand the distribution to more communities. But that aid never arrived.

The situation is critical; there is hunger in indigenous communities, and community kitchens have not been operating for months due to a lack of supplies, and production for self-consumption was poor because of the 2020 drought.

Faced with this distressing reality and the absence of the State, women continue to organize themselves in the community.

“There’s nothing else that can be done. The government itself doesn’t see the communities; it can only be achieved through organization, by uniting all of us. A program could be implemented to support Indigenous communities, not only Indigenous communities but also peasant communities. We always find ways to provide for our families, every single day. Where there’s no odd job, we gather pohã ñana (natural remedies), we go out and sell a little to bring food home to our children, and that’s how we live in the community,” Beatriz adds.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.