How to tell LGBT+ stories in sport without prejudice: a 13-step guide

In sports media, the representation and voices of LGBT+ people and athletes remain absent. Versus has launched a guide.

Share

By Georgina González, from Mexico City

In sports media, the representation and voices of LGBT+ people and athletes remain absent, and we rarely see intersections between human rights and the sports industry. Given its amplifying power, the sports industry could contribute to conversations and the building of more equitable and just societies.

However, when they do appear in the media, it's usually through "caricature, stigma, and scandal," says Ana Cruz Manjarrez, a communications specialist and member of the Versus , a Mexican organization that seeks to promote inclusive and professional content in sports media. Versus is implementing various strategies, one of which is the "Basic Guide for Inclusive and Prejudice-Free Communication ," aimed at journalists and consisting of 13 points to improve the portrayal of LGBTQ+ people in sports.

“An example of this was the article about Neymar’s mother’s partner. Even the copy they use on social media and the comments that followed those articles clearly showed us that the headlines and the way the article was written contribute to violence against the community. Furthermore, we noticed that sports journalism lacks interest in researching these issues and creating space to tell other stories,” Ana explains.

It is also observed that sports reports lack knowledge about basic concepts of sexual diversity, gender perspective, and sources that help to understand these realities.

The guide stems from a media analysis that Somos Versus began last year, one of whose variables is observing the presence and representation of sexual diversity in at least nine Mexican sports media outlets. It is also part of a collaboration with the British initiative Football vs. Homophobia , run by the Fare Network.

To develop the guide, the Versus team consulted other manuals and received input from researcher Siobhan Guerrero and activist Enrique Torre Molina. They also met with players from Mexico's professional women's soccer league, which helped clarify the urgent need for better media representation and the media's crucial role in combating lesbophobia.

LGBTphobic violence in digital environments

Versus, co-founded by sports journalist Marion Reimers , seeks to bring to the table debates around discrimination based on gender, race and class in order to improve content in sports journalism, rethink the discourses that are reproduced and change the narrative.

In 2017, they launched a campaign called “Beyond 140 Characters” to raise awareness of the various forms of violence perpetrated against female sports journalists in digital environments. Four years after its founding, Somos Versus has become involved in other projects and today seeks to “level the playing field,” promote women's sports, and focus attention on and tell other stories from a gender and human rights perspective.

“We want to bring together different perspectives that begin to link our work with the feminist movement by addressing other issues that include not only professional or amateur sports, but also women who are autonomous and use their bodies for different purposes that are not necessarily competition. We want to connect with this movement and our objectives through other themes,” says Ana Cruz Manjarrez.

“One grade is not enough, it is not representative”

In Latin America there are no studies on LGBTphobia in sports, however, some documents made in Europe show that there is still exclusion and discrimination towards people of sexual diversity in these environments.

According to a study by the University of Cologne (Germany), 90% of those surveyed consider homophobia and particularly transphobia to be a current problem in sports environments; in addition, 82% witnessed homophobic and transphobic language, of which 46% were trans women who reported being victims of direct discrimination.

Knowing this information can give us clues that these problems may be even more pronounced and normalized in our region. In this sense, sports journalism has an opportunity to contribute to building more equitable and discrimination-free societies, not by eliminating differences but by integrating them into its narratives.

“We want to demonstrate that the problem is structural and not a matter of 'you didn't like this article, but look, I once published an article about Kenti Robles (a Mexican professional soccer player who plays for Real Madrid), I'm not so bad at it,' because that's often the excuse they use. With the data in hand, we want to show that one article isn't enough, it's not representative,” says Andrea Martínez.

Beyond good practices

Andrea and Ana believe that good practices in sports journalism can help sports institutions or authorities to take notice of the needs of these populations and athletes in order to include them and improve their working conditions.

“If what’s on the sports media agenda doesn’t include things that involve the community, it might be much easier for the authorities to ignore it and therefore believe that they don’t need to do anything about it,” explains Andrea Martínez.

At the same time, seeing themselves reflected in the media can foster a sense of community among LGBT+ athletes. Ana Manjarrez comments that doing journalism with a human rights focus can be “an opportunity to talk, build community, and amplify their voices.”

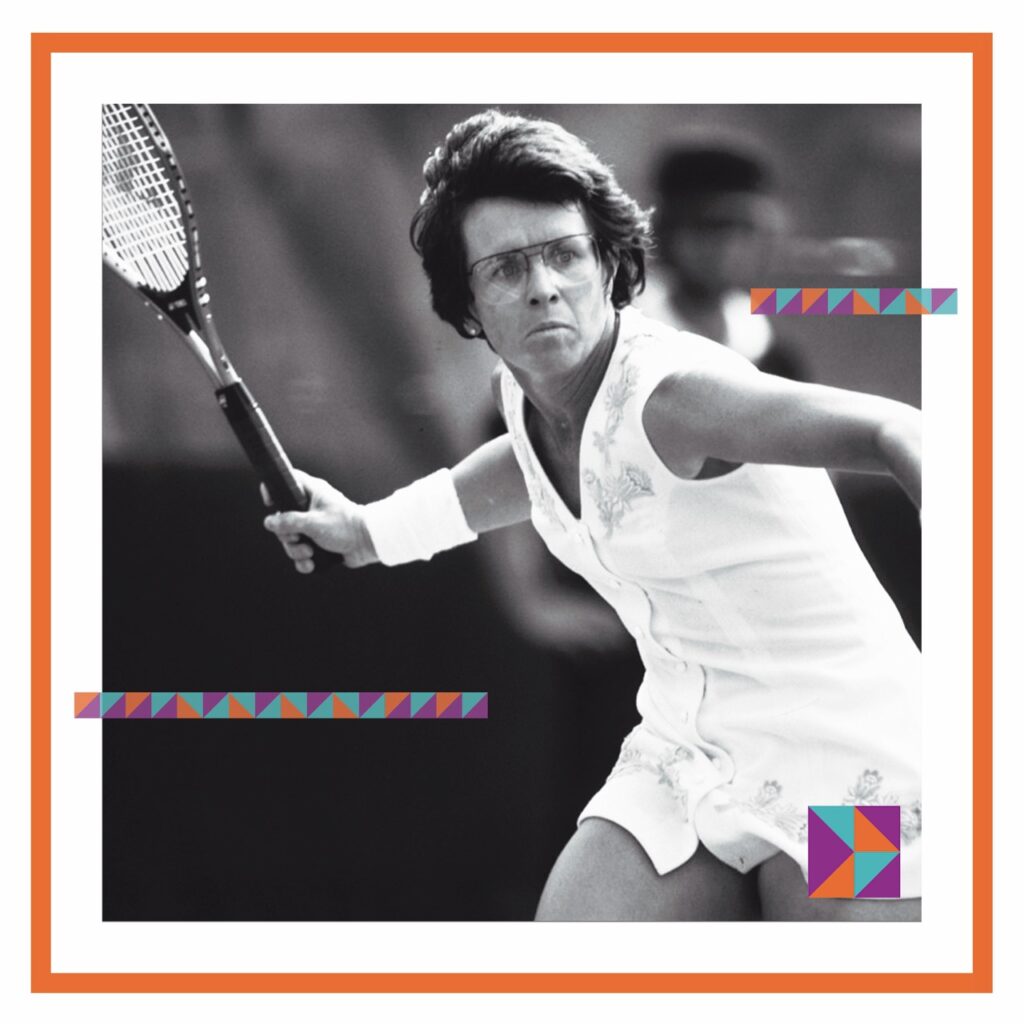

In that sense, women's sports and openly diverse athletes have been powerful voices that have taken these issues beyond their sporting environments, unlike gay athletes, who do not usually "come out of the closet" while active.

Martínez explains that this is because “the space of women's sports has always been a space of struggle. Women have had to fight to access sports, and I think that spirit embodies the struggle to live your truth freely, to express yourself without fear of reprisal. And in women's sports, there has been a development—I wouldn't say camaraderie, but rather a greater respect for individuality—unlike, I think, men's soccer, where things like maintaining hegemonic masculinity are celebrated more.”

How can journalism combat transphobia?

In recent years, sports have been used as a tool in hate speech that attempts to portray trans identities, and especially trans women, as "dangerous" or as enjoying an alleged "unfair advantage." Somos Versus believes that journalism can be a tool to combat transphobia.

“Part of good practice is being able to represent trans people as people who live, who play sports, who do the same things as all cis people, and who have the right to do so and should have access to all these spaces and activities. And I think it's also valid to look for medical explanations, but not only that; a human rights perspective should be included. Don't get stuck on this discourse of the supposed 'unfair advantage.' Intersex people aren't even talked about, and often what's published are the official decisions made by the authorities, and that's it. The case of Caster Semenya (two-time Olympic champion in the 800 meters) is very visible because she has spoken out, but how many similar cases are there in other sports and spaces? There, too, the media has fallen short and has failed,” warns Andrea Martínez.

Ana Manjarrez, for her part, believes that what's needed are answers. “Perhaps you want to understand why they can compete with women, because they are women, etc. But if you don't have the information explained in your language and in a way you can understand, you don't have arguments to defend it. And so, what we see most are the narratives from these groups where they portray it as unfair because of 'testosterone.' That's why it's important for newsrooms in Mexico to be open to covering these and other topics, and it's not even about taking sides. If you're aiming for neutrality, you can achieve it by balancing sources, which is another point in the Guide : always considering the opinions of the community you're impacting.”

““We urgently need to change the wording.”

For Somos Versus, the training and professionalization of sports journalists is fundamental, as is opening up spaces in newsrooms for LGBT+ journalists and people.

“It is essential that journalism curricula now include a gender perspective, so that students graduate with a much more developed understanding of this need; and the same applies to those who are already working as journalists, who must be willing to learn, to train, to deconstruct their own biases, and to apply this knowledge. It would require a lot of work, workshops, and perhaps the effects won't be immediate, but right now I don't see an easier solution,” says Andrea Martínez.

In Mexico, the path to training or professionalization for journalists can experience different gaps that point not only to how inaccessible it becomes outside of centralized cities, but also to the fact that media directors and editors do not seek to bring other knowledge to their workers to improve journalistic practice.

“There are very few opportunities and very few spaces to train yourself in things other than writing, spelling, and constructing a news story. And these opportunities aren't going to appear out of nowhere; this kind of training is necessary to help people escape the prevailing hegemony. There isn't a sports outlet where I haven't heard a misogynistic or homophobic joke, and these are everyday occurrences that are celebrated,” adds Ana Manjarrez.

***

As part of their commitment to improving narratives, Versus, in collaboration with Casa Tomada, will be offering the online every Wednesday in March. Registration is open here .

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.