How Chile is preparing for the fight to decriminalize abortion

Gloria Maira, coordinator of the Action Table for Abortion in Chile, analyzes the dimensions of the struggle, lessons learned from Argentina and the challenges ahead.

Share

By Airam Fernández, from Santiago de Chile

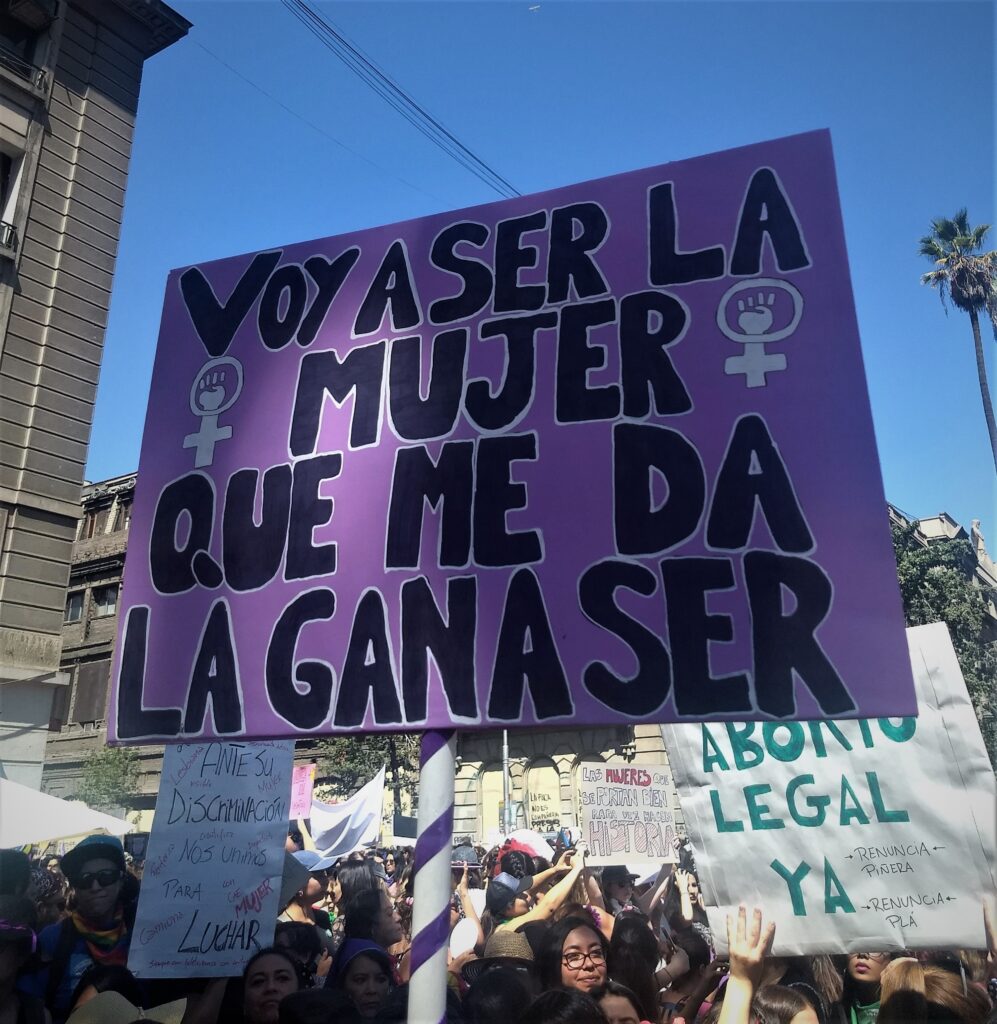

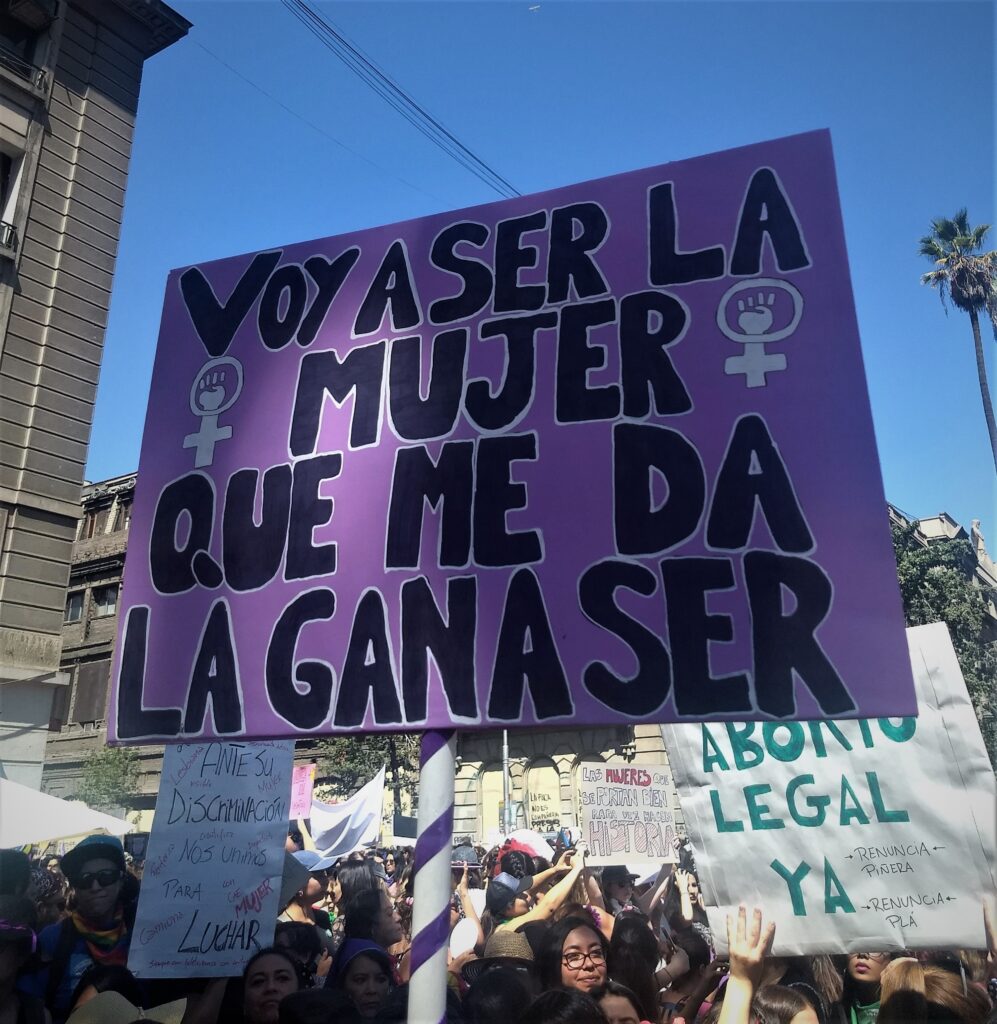

Photos: Josean Rivera /Presentes Archive/AG/AF/Courtesy of Gloria Maira

The green wave crossed the Andes: after the approval of legal, safe and free abortion in Argentina, Chile begins to discuss a bill submitted to Congress two years ago, which seeks to decriminalize the interruption of pregnancy up to the 14th week.

The official process begins on January 13, 2021. The country enters this discussion in a complex scenario. On the one hand, with a law on abortion in three specific cases approved in 2017. With many outstanding issues regarding sexual and reproductive rights. And just months after the Chamber of Deputies rejected the comprehensive sex education bill after failing to reach the necessary quorum. On the other hand, with a certain degree of confidence and optimism, in an atmosphere influenced not only by this Argentine milestone but also by the path the country is taking toward drafting a new Constitution.

Representatives Karol Cariola, Camila Vallejo, Natalia Castillo, Daniella Cicardini, Cristina Girardi, Claudia Mix, Emilia Nuyado, Maite Orsini, Camila Rojas, and Gael Yeomans are the authors of this bill, which was promoted by Corporación Humanas and the Chilean Abortion Action Committee. The legislative process begins in the Women and Gender Equity Committee of the Chamber of Deputies, in a session to which the Minister of Women and Gender Equity, Mónica Zalaquett, was also invited.

“ The processes in Argentina and Chile are different but also complementary ,” Gloria Maira, coordinator of the Action Table for Abortion in Chile and former undersecretary of the National Women's Service during Michelle Bachelet's second term, tells Presentes. In this interview, she contextualizes the local situation, analyzes the challenges ahead, and emphasizes the need for this cause, driven primarily by local feminist movements, to receive more support from other movements and organizations, including those representing sexual diversity.

-How did Chile arrive at the issue of decriminalizing abortion?

When we presented the project two years ago, it coincided somewhat with the debate taking place in Argentina surrounding a similar bill that ultimately failed in the Senate, but which had an impact on the entire continent. It was in the wake of that demand that we presented what will finally begin to be discussed today. Two years later, Argentina is experiencing a successful process after so much pressure from women and feminist movements. I believe these coincidences bode well for initiating the debate in our country.

The bill seeking to decriminalize abortion for women, lesbians, trans men, and non-binary people during the first 14 weeks of pregnancy coincides with the opening of the constitutional process. "This is very positive, because we are on the verge of electing representatives to draft a new Constitution. It is important that sexual and reproductive rights are part of this debate. The possibility of discussing it, and of it transcending the walls of Parliament and positively influencing the constitutional debate itself, places us in a historic period that could signify a very important change for the lives of women in our country."

-What lessons can you learn from the Argentine case, in light of what's to come for Chile?

The two projects are different. In Chile, we currently cannot achieve a bill that includes not only decriminalization but also access to healthcare through the public health system. The reason is that this is achieved through a parliamentary motion, which means, by law, that there is no possibility of committing public funds for it. Therefore, the bill only focuses on decriminalizing women's decisions during those first 14 weeks and removes this criminalization from the Penal Code . If the current government supported women's reproductive autonomy, as is happening in Argentina, we could ask them to formally introduce the bill, and then public funds could be committed for healthcare access. But unfortunately, that is not the case.

-How can greater visibility of dissent contribute to the struggle?

That's very important. As a working group, we've had conversations with many LGBTQ+ organizations, not specifically about this bill, but about sexual and reproductive rights, in order to forge a common path to strengthen our arguments, conviction, and strength in the face of the constitutional convention. And I believe that, to the same extent, greater support from LGBTQ+ groups would be very positive for the bill. We are very optimistic based on the Argentine experience. We saw what happened, how they organized and united around this cause, which demonstrates that it's not possible to move forward without sustained action from social movements, calling on other actors to join this initiative and help us exert pressure. Mobilization and citizen engagement are absolutely essential to achieving legal abortion in Chile.

Defective contraceptives and other project challenges

In August 2020, the Chilean Public Health Institute warned about several defective batches of the contraceptive pill Anulette CD. They withdrew it from the market and announced a health investigation, but said nothing about the women who relied on the pill.

According to local media reports, at least 29 women became pregnant while taking the drugs, and for most, motherhood was not part of their plans. The group Maira coordinates reviewed some of these cases and, since the lockdowns began, has spoken out not only about the increase in gender-based violence within homes and the lack of public policies to address this crisis, but also about the lack of access to sexual and reproductive health services and legal abortion during the pandemic.

-What did you see during the pandemic and how can that scenario give the project a greater sense of urgency?

During the most critical period of the pandemic, sexual and reproductive health care and access to legal abortion under the three grounds were not a priority in healthcare But the most serious issue was the difficulties with contraceptives, and not just Anulette. We have records of at least five hormonal contraceptives that turned out to be defective. This is serious because they are distributed not only in pharmacies but also through the public health network. We requested a concrete response from the Ministry of Health, specifically regarding what reparations will be offered to these women, but there has been complete silence. These women should have had access to safe abortion, and this is one of the reasons why this discussion is so important.

-What kind of challenges do you think are coming?

Conservatives and fundamentalists have always tried to frame the abortion debate as a confrontation between two lives, using arguments that are inconsistent with law, health, human life, and science. What 's crucial here is to demonstrate the connection between the reproductive autonomy of women and pregnant people, respect for rights and freedom to decide on life plans, democracy, justice, and access to a better life—fundamental principles and rights enshrined in legal instruments since the last century. What I mean is that we cannot imagine a better society if we are denied the possibility of deciding on such fundamental matters as our sexuality and reproduction . And being unable to do so reduces our citizenship to a secondary or tertiary status—a citizenship where we can vote but cannot decide on life itself, on the how and when of motherhood . So I think a major challenge ahead of us is to demonstrate this relationship and dismantle the narrative that has taken hold between our rights and the rights of a fetus, as if fetuses were people. The implications in terms of justice and democracy are much broader than that.

also important to continue pushing for sex education, because abortion isn't an isolated issue . Generally, the chances of doing good work in preventing abortion depend on having sex education and access to contraception. In other words, we're talking about a comprehensive view of sexual and reproductive rights. And in that context, abortion is seen as an exercise of autonomy, a right, and a freedom . It's unacceptable to think that exercising that autonomy in secrecy is a good sign for the kind of coexistence we want in our countries. We must fight against these kinds of thinking.

The implementation of the three grounds

Since September 2017, with the approval of Law No. 21,030, Chile has permitted abortion in three cases: risk to the life of the pregnant woman, lethal inviability of the embryo or fetus, and rape within certain time limits. The latest public figures from the Ministry of Health, updated at the end of 2019, show 1,535 abortions performed. However, the right is limited by the same law, which institutionalizes conscientious objection and allows healthcare professionals to abstain from performing the procedure in any of these cases.

This was a consequence of the fact that, once approved, the bill was sent to the Constitutional Court for review. According to a study conducted by Corporación Humanas, based on figures from the health authority, almost half (46%) of obstetricians working in public health services invoked conscientious objection in cases of rape. A quarter (25.3%) objected in cases of fetal inviability, and 18.4% did so in cases of life-threatening risk.

There are no official, or at least not publicly available, figures on the number of clandestine abortions performed in the country. However, another study by Corporación Humanas, published in 2018, estimated that the number of cases reaches 70,000 per year nationwide.

-Are there any challenges or lessons to be learned from the three causes?

"Of course, it was two long years of legislative process, and what was ultimately approved was considerably more restrictive than what President Bachelet initially presented. I think it's necessary to examine the agreements and arguments that led to its approval, but also to review how that bill was gradually restricted, and bring all of that into this discussion. It's also important to consider what happened afterward with that law in the Constitutional Court—what in other countries is known as the Constitutional Court—which arbitrarily incorporated institutional conscientious objection. That teaches us something in terms of the constitutional debate itself and the need to review that Court, its functions, and its powers. In fact, there's a whole discussion about whether it's even necessary to have one. The important thing here is to understand that you can achieve a tremendous chapter of rights, very rigorous, very strong in terms of recognizing social, sexual, and reproductive rights, but if you don't have a democratic institutional framework to support this chapter of rights, it will be reduced to a mere declaration. That's a very important challenge for us."

-Do you see a future for the project?

"I'm optimistic. But its success will depend largely on mobilization and sustained advocacy, lobbying, strong arguments, and street protests. The sustainability and permanence of these strategies are also important. Argentina persisted until it finally became law. They didn't succeed the first time, and that's something we should consider here; it's something that could happen. But we have to walk the path, and I believe the political context is in our favor ."

We are Present

We are committed to a type of journalism that delves deeply into the realm of the world and offers in-depth research, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related Notes

We Are Present

This and other stories don't usually make the media's attention. Together, we can make them known.