Intersectionality and decolonial feminism: revisiting the topic

What do we mean when we talk about intersectionality? Yuderkys Espinosa writes: "Decolonial and anti-racist feminism is selling like hotcakes these days.".

Share

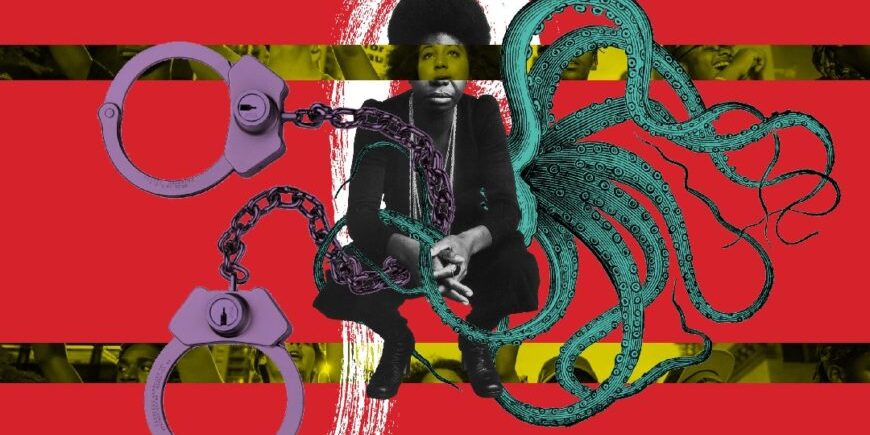

By Yuderkys Espinosa Miñoso /Illustration: Mrs. Milton/ Pikara*

"Mastering intersectionality goes beyond citing legendary names whose works we haven't taken the time to study in depth because, if we did, we might not cite them, since their positions are very different from the ones we are holding," writes Yuderkys Espinosa.

Decolonial and antiracist feminism is selling like hotcakes on every corner these days. While this fills us with satisfaction, I must admit that a sense of unease pervades me. As the movement expands, we face a latent problem: the risk of losing its identity and radicalism, a process by which many of the critical principles that inspired and guided us in the battles we waged against white feminism seem to be diluted or lost over time . I wonder how much of this process of expanding a decolonial consciousness ends up being more nominal than substantive.

When I first came to feminism, I saw how a handful of Black feminists were forming around 1992, creating a network to connect them, while simultaneously criticizing feminism for the lack of Black women in its spaces. This short-lived movement didn't gain much traction once many of its main leaders managed to integrate into mainstream feminism and its labor market, within state institutions and international cooperation agencies. A little over a decade later, and already in a new century, some of us who participated in or witnessed those events in 1992 were forced to revisit the issue, and we did so by deepening our analysis and revising the political program to be followed. I say we were forced by circumstances because, after having persisted in being part of the unified feminist movement under the banner of sisterhood among women, we ended up realizing how false that was. From there emerged a radical gesture that allowed for a powerful critique of both hegemonic and counter-hegemonic feminism (from which some of us came), observing its complicity with Eurocentrism, and therefore with racism and coloniality. In this process of detachment, we decided to actively engage in promoting a movement of non-white feminists capable of confronting the most widespread feminist understanding and its program of liberation. We have come to know this new moment as decolonial feminism or anti-racist feminism. But in the meantime, new terms have appeared or have been reappropriated: Black feminism, Afrofeminism, intersectional feminism , etc.

This latest nomination highlights what is perhaps one of the most important and best-known contributions of Black feminism: intersectionality. This perspective is what racialized feminists, and increasingly, and unexpectedly, feminists of all kinds, have claimed as common ground. Over time, however, those of us who introduced it into Latin American feminist politics, those of us who have dedicated ourselves to its rigorous study, see an increasingly widespread use of the noun "intersectional" to justify interpretations of reality that, in my view, are increasingly distant from those that, since the 1970s, initiated the thought process that led Kimberle Crenshaw to coin the term. If the first decolonial anti-racist feminists of Latin America and the Caribbean had already observed the advantages and weaknesses of intersectional analysis, in recent years we have seen how these problems have worsened under a reception, in my view, distorted, which gives continuity to the feminist narrative and program initially produced by the white feminism that we have sought to confront, but which now appears disguised under discourses or self-identifications that proclaim to assume this perspective.

To this we must add a new problem we hadn't anticipated: Black feminism, or contemporary Afrofeminism, by naming itself from a specific identity, carries with it the problem of identity politics . In short, this refers to the false belief that there is a unity between experience, politics, and desire. While intersectionality is indeed supposed to emerge only from racialized bodies, this doesn't apply in reverse: not all racialized bodies will necessarily develop this perspective "naturally." Some of us have dedicated years to studying it, applying it, and learning from experience by observing its developments and limitations. Mastering intersectionality goes beyond citing legendary figures whose work we haven't taken the time to study in depth because, if we did, we might not cite them, since their positions are very different from our own.

We are at a point where white women and gender-nonconforming people, as well as racialized or marginalized comrades, speak interchangeably about intersectionality and even attempt to teach what it is, while one watches with dismay as they leave the feminist analysis and politics it was intended to oppose untouched. Intersectionality is not an identity; it doesn't fall from the sky, it's not inherited, it's not a natural condition belonging to any group. This idea that a subject, simply by virtue of their condition, naturally carries or represents a political project is a grave error that we should avoid. Intersectionality is also not about researching or working with Indigenous, Afro-descendant, or working-class populations; in reality, this has always been done. If, by using the term intersectionality, the feminist discourse remains untouched, if the argument, the analysis, the approach is merely to apply the strongest (white) feminist convictions and truths to understanding the world of marginalized people and double down by pointing out that everything is exacerbated there, then we are seriously misunderstanding the task.

Intersectionality, on the other hand, leads us toward a new form of interpretation that abandons the familiar, gender-centered feminist perspective for a more comprehensive one. The failure of the main critical systems for interpreting the social order—Marxism, feminism, critical race theory—lies in the fact that each attempts to offer an interpretation based on what it assumes to be the fundamental axis of domination. Starting from this assumption, a false unity of the thing defined by this axis or category is constructed, along with a false idea of the category's autonomy . But there is an inseparability between domination and the experience of domination that transcends the categorical method that attempts to explain it.

But, as María Lugones warns us, intersectionality doesn't solve the problem, it only reveals it . Intersectionality can give the false impression that beyond the intersection, these sets exist and function independently. The reality is that the set of "gender," for example, is a historical construct conceived for and experienced by white women, and everything derived from it is conceived from their perspective. Therefore, all the truths, positions, and strategies developed from the category of gender are USELESS for understanding the conditions of our domination as racialized. This is precisely why doing intersectionality is not about taking those interpretations and replicating them for Black women, stating that "in addition to racism, we are affected by the gender order." To assert this is to fail to understand that gender is always conditioned by coloniality and the racial structuring of the world.

To clarify what I mean, let me give you an example. A large majority of feminists who today claim to have an intersectional or anti-racist perspective (including Black feminists), as well as a segment of academia and institutions, have indeed incorporated a sensitivity to racism. This has not, however, meant abandoning the white feminist viewpoint when it comes to the problems that feminist theory and programs have defined as their own. So you find feminists who are outraged by the murder of George Floyd or by the Chilean state letting Machi Celestino on hunger strike after an unjust sentence. These are the same people who are horrified that prisons are full of people from impoverished neighborhoods, Black and Indigenous men, migrants from poor countries in the Global North, and racialized people in general. Let's just say that, faced with these problems that clearly stem from a critical analysis of racism, there seems to be a consensus of widespread indignation within our feminist and leftist movements.

However, it is highly contradictory that these same people will base their demands for justice for women on exemplary condemnation (through the courts or through public shaming and social ostracism) of those who have committed any kind of offense against "women," from the smallest infraction to the most cruel and ruthless, such as homicide. Feminist justice will demand more prisons, greater police control, and harsher sentences for rapists, abusers, murderers, traffickers, etc. When it comes to minor offenses, the level of cruelty will be no less, even if it is carried out through public shaming and persecution. For feminist justice, all men are equally suspect, regardless of their racial or ethnic origin, their social status, or their background. If it has already been accepted that women are not a monolith, this does not seem to affect the treatment of men. They will all receive the same treatment… at least in theory. Because, we must remember, the most visible and representative faces of these macho men, abusers, rapists, murderers, drug traffickers… are mostly racialized men.

However, beyond an unjust and racist judicial system that condemns the poor and frees the powerful, beyond the conviction of innocent people simply because of their appearance, these men are there because they have committed a crime, not because they are saints. We keep this very much in mind when it comes to condemning them and demanding justice because they have harmed a woman, but we seem to forget it or choose to treat it differently when we are outraged that prisons are full of Black and Indigenous men. While in one case we are relentless in demanding their heads, in another we are outraged by a system that systematically condemns them to be the dregs of society. It would seem as if it is not the same person, but no, in the end it is the same racialized individual who in one case elicits empathy for being a victim of a social order that condemns him, and in another case only deserves our cruelty, repudiation, and condemnation; if before we were horrified by police actions, now we are the executioners who announce their death, shouting at the State and the police to act.

How can we explain this? This is precisely what intersectionality warns us about. It's about how we respond according to the definition of the problem and the treatment of it developed from each of these analytical frameworks produced from a central category. Each problem has been defined from a system of interpretation, and from there, the type of response, attitude, or solution to it is defined. When dealing with classic problems of the anti-racist struggle, we will apply the treatment that stems from this program of interpretation and action; when dealing with "women," we will apply the analysis and political program of… white feminism!

So let's be clear: either we agree that they should all be killed or imprisoned, or we begin to seriously consider the constitutive processes of this violent masculinity, which, of course, exceeds gender analysis, because it's not just about being given balls and guns from childhood; it's about historical and structural conditions that shape that subjectivity.

The challenge posed by intersectionality involves the gradual abandonment of a categorical and additive perspective, in favor of a more alchemical one where the gender order is always racialized and geopolitically mediated ; one where these approaches merge, producing a new one, far removed from the formulations to which feminism has accustomed us. This allows us to move towards a very different kind of politics, according to the place we occupy as a community within the matrix of domination and, concomitantly, the way in which we act to confront it. We should not forget this in the analysis or in the definition of strategies to address the problems we face from a non-dominant perspective and from the perspectives of those most affected by coloniality.

*This article was originally published in Pikara. To learn more about our partnership with this publication, click here .

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.