Disability activism: from the social stigma of disability to political identity

In the heat of the LGBTI+ struggles, the multiple identities of disability or functional diversity propose new dialogues.

Share

By Ivana Romero

Cover photo: Luna Irarzábal photographed by La Baraja

In the heat of the LGBTQ+ struggles, the multiple identities of disability or functional diversity propose new dialogues and intersectionalities with personal and political biases. Four activists from Latin America share their journeys to embrace and defend their desires.

You did wrong, very wrong.

That's what the principal of a school in La Plata told Ayito Cabrera when she saw him. Ayito is 32 years old, had completed the coursework for a teaching degree in Literature, and his resume, according to the institution, was impeccable. That's why they called him, to fill a vacant teaching position. But things changed when he arrived. The secretary got angry; so did the principal and the school's legal representative. They closed the office door and told him that showing up "without explaining what was wrong" was irresponsible, that they had an elevator but it wasn't working, and that they weren't going to remodel the school because of this "little matter." Ayito tried to remain composed. He wasn't going to give them the satisfaction of crying in front of them.

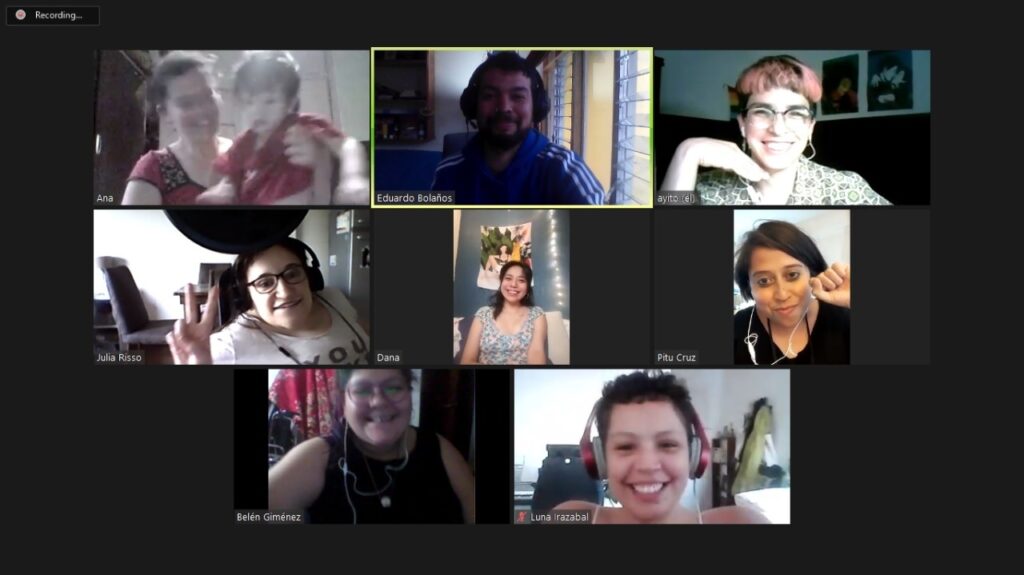

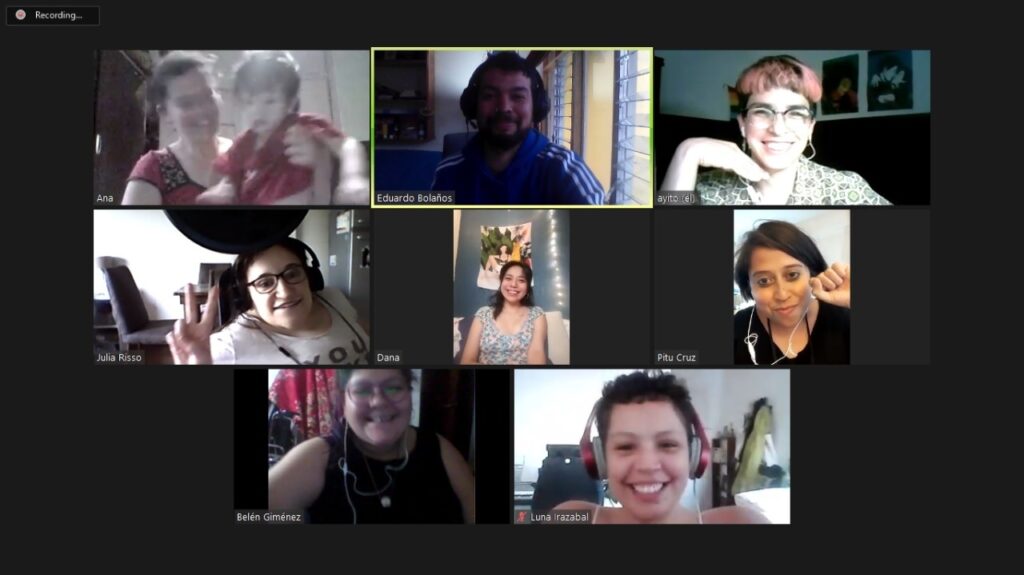

“What was my terrible sin? Not telling them I use a wheelchair,” explains Ayito, who also identifies as a non-binary trans person, social media communicator, radio columnist, and writer. “It was too much for them. But for me, too. I cried while waiting for the bus and finally went to the disability legal clinic at the Law School here in La Plata, where I live. That's how I started reading laws and realizing that we, disabled people, have many rights. And we've decided to assert them,” they add. That's how, during the pandemic, they harnessed the power of social media and began meeting with others to shape and develop La Barra Disca, a new activist organization in development, with members from here and other Latin American countries.

When asked how they prefer to be referred to in the context of this interview, they say: “I identify as a person with a disability.” And they clarify: “There are other terms, like 'functional diversity,' but it's a label that doesn't fit me . other comrades. Others identify as disabled, handicapped, and more. We transform every violent word into a source of pride. Our political identities must be respected as such and put on the agenda.”

December 3rd is the International Day of Persons with Disabilities. On its official website, the World Health Organization recognizes that “almost all of us will experience a temporary or permanent disability at some point in our lives,” yet few countries implement its vast body of protocols, laws, and recommendations. In 2008, for example, Argentina adopted the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities through the passage of Law 26.378. This progress is complemented by other legislative advances. However, its full implementation remains an outstanding issue.

“Ableism has put it in our heads that we must live in isolation.”

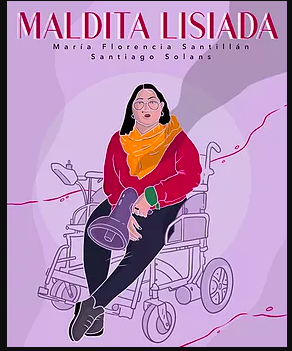

“Everyone’s identity is multiple and ever-changing, shaped by issues of class, race, and gender. Disabled identity is also political . It’s very difficult to understand this because disability has historically been seen as an individual problem. That forces you to stay within the four walls of your home, and in social terms, it’s only acceptable to go out to the doctor. Otherwise, you’re a burden,” explains Florencia Santillán, a 28-year-old journalist who lives in Carlos Paz and is the author of the book Maldita lisiada (Damn Cripple), co-written with Santiago Solans.

“Ableism, that is, the logic that establishes which bodies are valid and which are not, has instilled in us the idea that we must live isolated or confined to our homes, always reduced to children under the care of our parents. We must be good people, submissive, kind even when we are told things like 'poor thing' or 'at least you're intelligent.' Our response is that all embodiment is political, that the binary of what is considered good or bad hides a diversity of which we are all a part . Because the aspiration for the 'perfect body' is, in truth, one of the many ways in which power exerts its patriarchal logic for you and me. The truth is that we are all what our desire is. And our desire is powerful and political. Zero childishness, zero 'poor thing',” she adds.

Perón's cripples

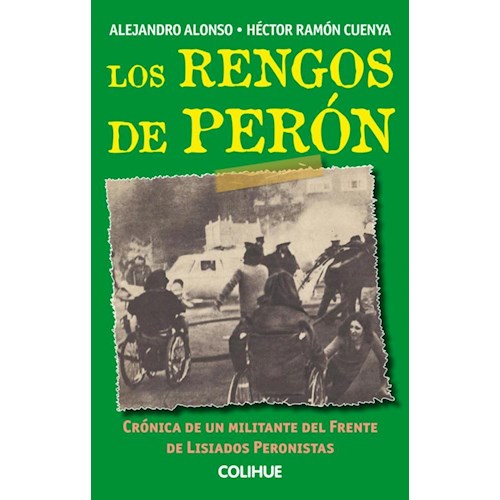

Some traces of political organization can be found in the book *Los rengos de Perón ), by Alejandro Alonso and Héctor Ramón Cuenya. Published in 2015 by Colihue, it recounts the activism of young people in the 1970s within the Peronist Disabled Front. From then on, the traces are faint. However, in 2019, the Disabled Pride contingent made its first appearance at the LGBTI+ Pride March. Laura Alcaide, one of the members of this collective, recounts: “Orgullo, which is clearly a tribute to the struggle of Carlos Jáuregui and other activists, emerged during a trip to a gathering of women with visual disabilities that we took with another colleague. There, we began to consider the need to stop compartmentalizing ourselves by disability or by gender non-conforming people, for example. In fact, we have experienced discrimination within feminist spaces because, for our diverse bodies, participating in an assembly or being in the street is a different challenge, and this isn't always understood. So we created a disabled contingent, inclusive and accessible, where people with various disabilities and allies came together, and we participated in the Pride March for the first time. It was beautiful.”

Eduardo Bolaños Mayorga, 31, lives in San José, Costa Rica, where, he explains, there are progressive laws but no social processes to accompany those changes. “Personally, I have no problem acknowledging that I have one arm. It’s my way of saying that I’m not interested in being visible only in that way, but I’m also not interested in being ‘normal,’ and I do believe in the need to make other bodies and other forms visible. It’s not just a formality but an ideological struggle: one thing is to guarantee inclusion based on the parameter of ‘normality,’ and another is to do it based on the acceptance of diversity, where there is no superiority whatsoever. That’s the direction we want to go.”

Feminism as a gateway

For Luna Irarzábal, a university student and public employee living in Montevideo, her entry into feminism was essential. “I began to think about my political identity after thinking about my identity as a lesbian feminist. I explain it this way so it's clear, although the process was and is dynamic: no one ever has just one identity, and that identity isn't always the same,” says this activist with the organization Ovejas Negras (Black Sheep). She identifies as a woman and explains that while inhabiting public space, due to its architectural shortcomings and its violence toward any form of dissent, is a challenge for anyone, in her case the challenge is even greater.

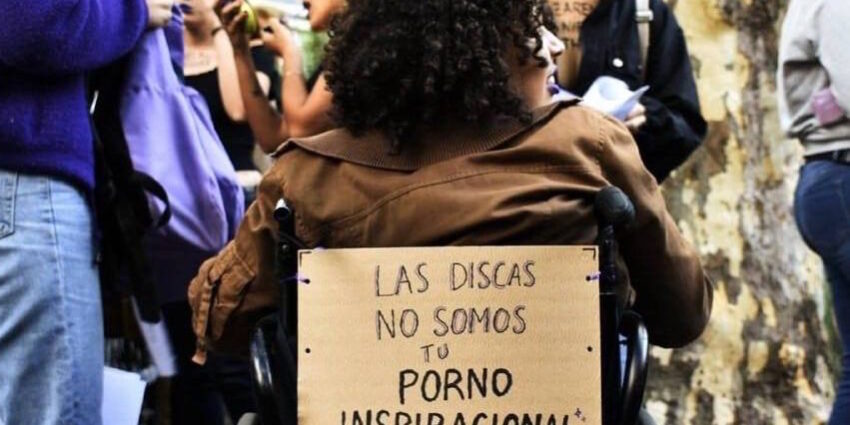

“If you have an obvious disability, that’s what people see when they look at you. Then you’re an angel and they have to take care of you and take you to church. But if you’re a lesbian, trans, whatever, you become sinful, and if you use a wheelchair, that’s your problem . When you proclaim your desire, your identity, your sexuality as a disabled person, people short-circuit!” she adds. And she laughs. Because without dark humor, she assures us, everything would be more difficult.

Ayito Cabrera is enthusiastic about the possibilities for activist expansion that are beginning to open up in the heat of the LGBTQ+ struggles. Within this framework, the multiple identities of disabled people propose new dialogues and intersectionalities with personal and political dimensions . This expands the possibilities for achieving economic autonomy that allows each person to live, study, work, or love without depending on others; to actively participate in the creation and respect of laws; or to use social media as a space for dissident construction beyond borders ("many say that activism only happens in the streets, but we know there are other ways too," she says ). Ayito summarizes: "Now we want to build the Disabled Greater Homeland."

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.