Only the gods do not die

Maradona's journey from Villa Fiorito to where he ended up was like a world within a world. He was called arrogant, a homophobe, a faggot, a "head," a womanizer, and a violent sexist.

Share

By Flavio Rapisardi

Only gods don't die. Not because of their "nature," but because their names reflect, signify, and entwine something beyond themselves: wills, hatreds, loves, and indifference. Maradona died, so by simple syllogism we can deduce that he wasn't a god, but a man, a male to be more precise, who experienced all the contradictions not of a supposed and abstract human nature, but of those of us who live in this country, the tip of a continent punished by its own people and by others. However, his death knocked millions of people out, myself included. And not because I liked soccer—besides being an Independiente fan, a team with a well-earned reputation for being cold-hearted, I'm an old-fashioned wimp whose first gift from my father was a size five leather soccer ball that rotted in the garage—but because his name means so much to me, even today. At least more and better than what a supposed feminist wrote in a nasty tweet, celebrating her death applauded by others from a supposed feminism or lgbtiq+ identity.

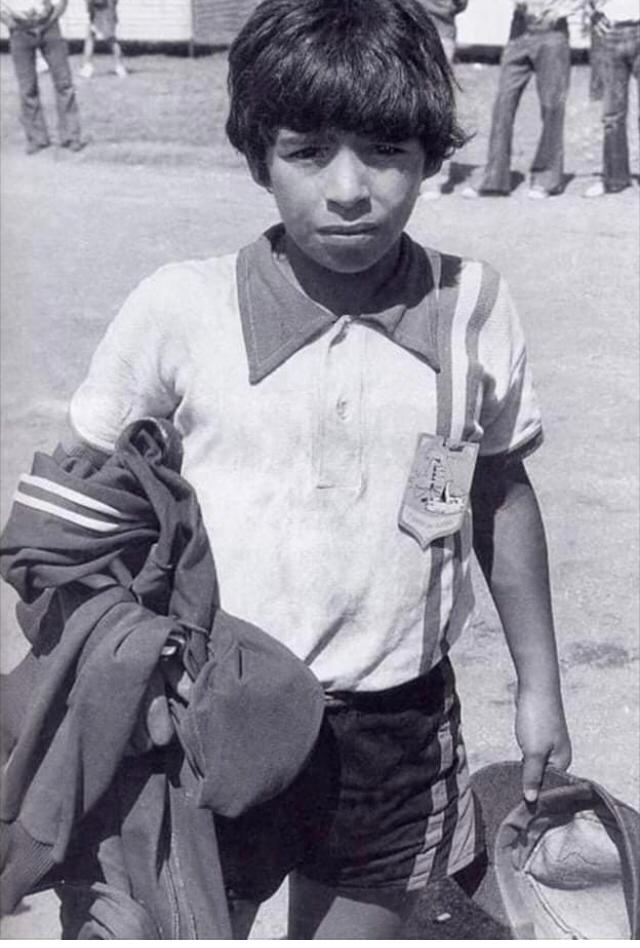

Maradona's journey from Villa Fiorito to where he ended up was a journey through worlds within worlds. He was called arrogant, a homophobe, a faggot, a "head," a womanizer, a violent macho. Regarding his arrogance, I know nothing more than that one cannot escape abjection by preaching "good manners" from the privileged, from that police of decorum and good customs that operates on both the left and the right alike.

Being gay and a homophobe are compatible; you can be both. But at least I'm not interested in what he did with his sexuality, and I never heard him discriminate any more than so many others who wear green scarves, purple flags, and/or rainbow flags. What 's more, I remember him wearing a t-shirt that said, in English, "No place for homophobia and racism." Now, I do believe Verónica Ojeda and Rocío Oliva, even though in one case it was a "rumor" and in the other a formal complaint with evidence, and nothing justifies the gender violence that Diego inflicted on the body of at least one of them. Irredeemable and unjustifiable marks that are part of a longer narrative, full of twists and turns, of those contradictions that led Søren Kierkegaard to say, "They will say that I contradict myself; it is because I have multitudes within me . And that's what Maradona had written on the body of a starving kid who got covered in flies and lived life, for better or for worse, everyone will know.

I still remember Mercedes Sosa's challenge to Diego when he said he wanted caviar for his daughters. The woman from Tucumán, with that matriarchal wisdom and simple way of speaking, advised him against it because there were still hungry children in the country. She reminded him that in her childhood in Tucumán, her mother would take food from her own mouth to give to her, given their daily hunger. And Diego understood, with humility and a gesture of affection, and he dedicated himself wholeheartedly to opposing the FTAA, to supporting populist governments despite his brief flirtation with Menem back in the '90s, to reclaiming his past, his life, his history, and making it a story of pride. Who is without sin? Aren't the feminists and LGBTQ+ people who celebrated Macri's policies necessary accomplices in the plundering plan that led to the deaths of thousands of compatriots, despite the validity of demands like equality and legal abortion?

Today I cried for Diego with my husband while watching TV because I don't have a "purist" counter or a cop's hat, and because in him, as in all of us, the "double conscience" became entangled—which isn't double standards, but rather that phenomenon of life's precarity that doesn't make everything relative, but situates and complicates the easy chatter . Today I remembered my childhood as a working-class kid in Sarandí, the size five white ball, how I faced contempt not only for being gay, but also for being poor at home with a bathroom without a shower and no water heater in the yard.

Diego Maradona wasn't a god, but his name, whether we like it or not, entails many antagonisms, not only those of gender and sexual identities, but also those of ethnicity and class, which he also embodied in Naples when he led the Neapolitan "little black heads"—the "little black heads" in the anti-gorilla slang—to victory, showing the fascist Lombard League that they had a history to be proud of. Maradona died like any human being, but the tapestry woven by his life has many colors that no single, exclusive "eye of God" can capture. On the contrary, the complexity of this fabric will outlive him, always as human as the living God in whom I believe.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.