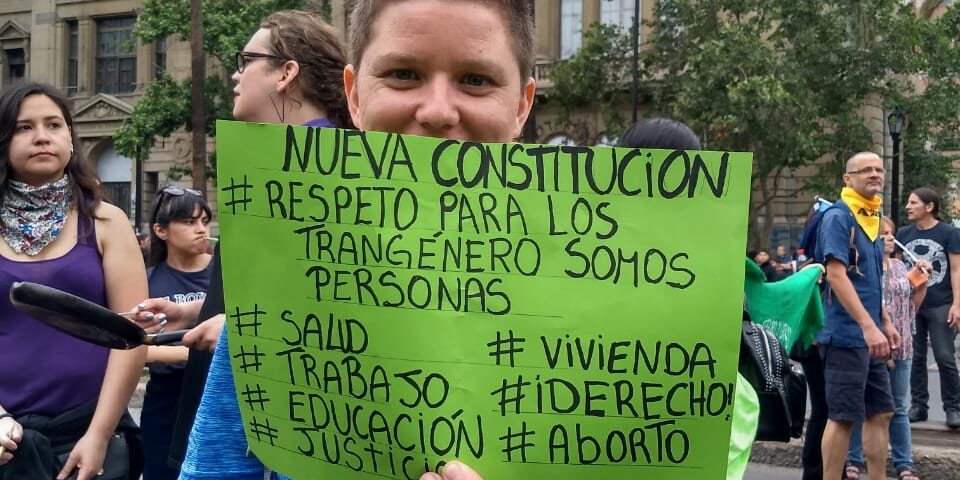

Transfeminist proposals for a new Chilean Constitution

Presentes spoke with some of the organizations on this platform and with other activists who also stir up the debate from their corners.

Share

By Airam Fernández

Photos: Josean Rivera / Courtesy of the organizations

The coronavirus changed many plans, including the timeline for a new Constitution in Chile. It was planned that 14 million Chileans and migrants eligible to vote would go to the polls (on April 26) to make one of the most important decisions in the history of Chilean democracy: to choose whether or not they want a new Constitution, and to replace the one that has governed the country since 1980, from the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet. The pandemic disrupted these plans, and the political forces agreed on the need to postpone it until October 25. On July 31, President Sebastián Piñera addressed the issue during his State of the Nation Address, stating: “Democracy is founded on the freedom of its citizens, and that freedom demands responsible conduct. With the agreed-upon plebiscite just weeks away, we must exercise this freedom and responsibility rigorously, especially in times of crisis, which often tend to be breeding grounds for all kinds of populism. […] We all have the right to propose changes to our Constitution and laws, through the procedures they establish. But we must all respect them, and especially those authorities who swore or promised to do so at all times.”

It will be the first national plebiscite since 1989. But it will also be the result of a historic agreement between the country's main political parties, in response to the social unrest that erupted in October 2019. When it takes place, citizens will not only have to answer whether they approve or reject the idea: they will have to decide whether the drafting is done through a Mixed Convention, made up of popularly elected members and sitting members of parliament; or a Constitutional Convention, made up exclusively of popularly elected members.

If the result is favorable, the body working on the general text must validate its decisions and vote on the complete draft, including its chapters and articles. This will require a two-thirds majority vote of the Convention members.

Although the shift in the political agenda and the pandemic brought some respite to the polarization, those living in Chile haven't forgotten the problems that drove them to the streets nine months ago. When the health crisis was just beginning, feminist and LGBTQ+ organizations, among other groups, formed the "Approve Diversity" campaign to think collectively and contribute to the constitutional debate.

Presentes spoke with some of the organizations on this platform and with other activists who are also stirring up the debate from their respective corners. They agree that a new Constitution wouldn't solve all the country's problems, but it would be a very important first step. This is what they propose to avoid being left out of the process and to achieve a Constitution that includes everyone, with their identities and rights recognized.

Changing the foundations of the institutional framework

Article 1 of the Chilean Constitution states that “people are born free and equal in dignity and rights.” Some activists believe the concept of equality should be reformulated, as they consider it to be defined by heteronormativity and a gender binary.

Rodrigo Mallea, an activist and graduate in Legal and Social Sciences, insists on this point: “The Constitution cannot begin by assuming that all people are equal or in equal conditions. What a new draft must do is ensure that all people can be materially equal. That is to say, equality must not be indifferent to structural inequalities, and based on these circumstances, it must consider them and seek to eradicate them.”

Among the proposals of Gloria Maira, coordinator of the Action Table for Abortion in Chile and former undersecretary of the National Women's Service, the most notable is to move towards a concept of substantive equality: "That is, equality by results."

“In that sense, it is important to change the foundations of the institutional framework. For example, the concept of people is binary and only includes men and women,” says Constanza Torres, director of the LTBIQ+ Commission of the Association of Feminist Lawyers (Abofem).

Franco Fuica, a transmasculine activist and president of Organizing Trans Diversities (OTD), also proposes eliminating that binary vision: “The Constitution must be rewritten from a human being's perspective, regardless of gender.”

For Gonzalo Cid, leader of the Movement for Sexual Diversity (MUMS), the Constitution must contain guarantees for an institution to monitor laws such as the Anti-Discrimination Law (known as the Zamudio Law), along with the incorporation of a gender and sexual diversity perspective "to review and correct the current legal system, changing all discriminatory norms and ensuring that laws, regulations and decrees do not discriminate in the future."

What Alessia Injoque, a trans activist and president of Fundación Iguales, proposes is along similar lines: “It is essential that the principles of equality and non-discrimination redraw the moral map of the institutions, in such a way that they allow and guarantee the LGBTI community to have access without any distinction to the institutions of the State.”

Although the current charter does not define the concept of family, Article 1 does establish that it will be the "fundamental nucleus" of society. Constanza Torres, from Abofem , proposes eliminating this principle and moving to the idea that the nucleus of society is "people as a whole."

The Lesbian Group Breaking the Silence (RS) proposes broadening that vision to include diverse families: “Thanks to assisted reproductive technologies, lesbian-mother families are now formed, for example. They don't have legal recognition due to the Constitution, but they coexist.”

For a guarantor and present State

One of the major criticisms of the current Constitution concerns the subsidiary role of the State, which, while not explicitly stated, defines in many ways how Chile functions today. For example, Article 1 states that “the State recognizes and protects intermediate groups through which society is organized and structured and guarantees them adequate autonomy to fulfill their own specific purposes.” In other words, a State that does not directly provide rights such as health, education, water, or social security, but rather leaves them in private hands. Now, demands are being made for the State to have greater participation and involvement in the provision of basic goods.

“Today, the subsidiary state limits state participation until it’s already too late, after it has given absolute freedom to private entities. This is problematic because private entities seek to satisfy their own interests and not collective interests, which are usually threatened or neglected by this approach,” says lawyer Rodrigo Mallea. Changing this also opens up possibilities for a better quality of life, argues Gloria Maira: “What we need is a state that is both guarantor and active.”

RS proposes that the State assume concrete responsibilities regarding the financing of social, rehabilitation, and support programs for people with disabilities, such as the Telethon, a televised charity event held annually to raise money for these purposes. “It is necessary for the State to stop being just another spectator of this activity and take responsibility for providing healthcare guarantees to those who need support due to disabilities, both congenital and acquired,” argues this organization made up of lesbians.

Fundamental rights for diversity

Mallea says it's necessary to understand that the demands of sexual diversity "are cross-cutting and structural," and that this is the main challenge in this area. "It's positive that there is explicit recognition, in principles and rights, for example. But the recognition must be throughout all rights and the entire Constitution, and not just in one section or an appendix," this lawyer argues regarding the space that LGBT people should have.

In the chapter on rights, Constanza Torres of Abofem says it is important to incorporate economic, social, and cultural rights, but with a gender and diversity focus. “Let’s think about rights such as housing, education, health, and work, from which the LGBTI population has always been excluded,” she argues.

Alessia Injoque, from the Iguales Foundation , proposes a charter "focused on equality in marriage, parental rights, and identity." She also emphasizes the need to recognize and protect families, regardless of their composition, and to prevent discrimination rather than simply punish it.

The right to sexual education and reproductive rights are essential, says Franchesca Carrasco, an activist with the Neutres Collective. Gloria Maira adds the right to a life free from violence for women and girls, the right to participate in political representation, cultural and environmental rights, along with explicit recognition of domestic work, which “must also be accounted for in the National Accounts.”

For Franco Fuica of OTD , it is necessary to enshrine in law the right of every person to develop their potential and for this right to be truly guaranteed by the State. He says this with transgender people in mind, and despite the Gender Identity Law that came into effect last December.

Alejandra Soto, a trans activist and president of the Amanda Jofré Independent Union of Sex Workers, elaborates on the rights of trans people. “Not being recognized in the Constitution is an additional obstacle to accessing healthcare, which we have long demanded be addressed from a comprehensive perspective. To date, at least for our members in this organization, we are viewed as men of working age. Therefore, in all social protection programs and benefits provided by the public health system, we are excluded because we do not meet certain criteria that others have deemed important,” she says.

Other fundamental rights that RS adds include the right to free expression “without being attacked, mutilated or punished for peaceful events”; the right to access free and quality education; access to universal, quality and timely health care; the right to decide about one's own body; the right to have and be part of a recognized family and respect for different family compositions: “This last will also contribute to better and more expeditious processes for medical assistance for pregnancy, adoption processes and recognition of lesbian-mother families through parentage rights,” they add.

That all of this is permeated by a logic of intersectionality or multiculturalism is crucial, adds the Abofem spokesperson, especially "so as not to exclude indigenous peoples, migrants or people with disabilities."

Feminist approach

Is it feasible for a country like Chile to achieve a feminist Constitution? There is a consensus that it is.

Rodrigo Mallea says that gender parity is not only necessary, but legally possible: recently, both Congress and the Senate approved gender parity in the constituent body that will draft a new Constitution. “One aspect that can substantially help achieve this is that the Constitution will be written by a considerable number of women. And even if they are right-wing, we hope they will be more progressive regarding the rights championed by feminism,” says the lawyer. Franchesca Carrasco, from Neutres, warns that the inclusion of all women from the dissident movement is also fundamental.

Franco Fuica , from OTD, emphasizes something important from the movement's foundation: “Feminism is not a construct solely for women, as is often portrayed, but rather a political construct defined by equality, by the idea that all people have the same value. In that sense, what the social movement has achieved is a powerful uprising against oppression, with great resolve and awareness, and that clarity stems from the feminist framework, which is partly what allows us to enshrine these issues at the constitutional level today.”

In terms of content, Constanza Torres argues that a new Constitution can only be feminist if it is based on the premise of gender equality in its institutional foundations: “The prevention, punishment, and redress of gender-based violence must be incorporated as one of the fundamental principles, leaving the details to the law. Gender equality must also be enshrined through quotas or reserved seats in certain branches of government. Likewise, more serious and committed work must be done regarding the gender perspective in the chapters on the Armed Forces, the Judiciary, the Constitutional Court, and Congress.” Torres also raises the need to explicitly state that the State has the duty to “respect and promote the wide diversity of women that exist in the country.”

Alessia Injoque warns that women and diverse people participating in the drafting process must ensure that there are no restrictions on bodily autonomy in the new charter: “Such as the protection of 'the unborn,' which appears in the current Constitution and is used as a reference to oppose abortion.”

For Gloria Maira , the feminist perspective stems from the desire to eradicate patriarchy, colonialism, and extractivism as forms of domination, but it cannot be limited to the new text that is yet to come: “I feel that beyond declaring a feminist Constitution and incorporating all these elements we've been talking about, we must view it as a long-term horizon, where what we propose today will surely be insufficient. I believe it is a continuous work of construction and deconstruction precisely based on that desire.”

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.