Viviana Avendaño: lesbian, feminist and picket line activist

She was the youngest political prisoner in Córdoba. She died on June 10, 2000, along with her partner Laura Lucero, in a suspicious crash during a social conflict.

Share

By Lucas Gutiérrez

Photos: Julio Albornoz, Carola Murúa and courtesy of Alexis Oliva

“I’m a lesbian, I’m a feminist… and I’m a piquetera”: that’s how Viviana Avendaño defined herself. Shortly before the State Terrorism, she was also the youngest political prisoner in the province of Córdoba. She died on June 10, 2000, at the age of 41, along with her partner Laura Lucero, in a suspicious car crash during a social conflict.

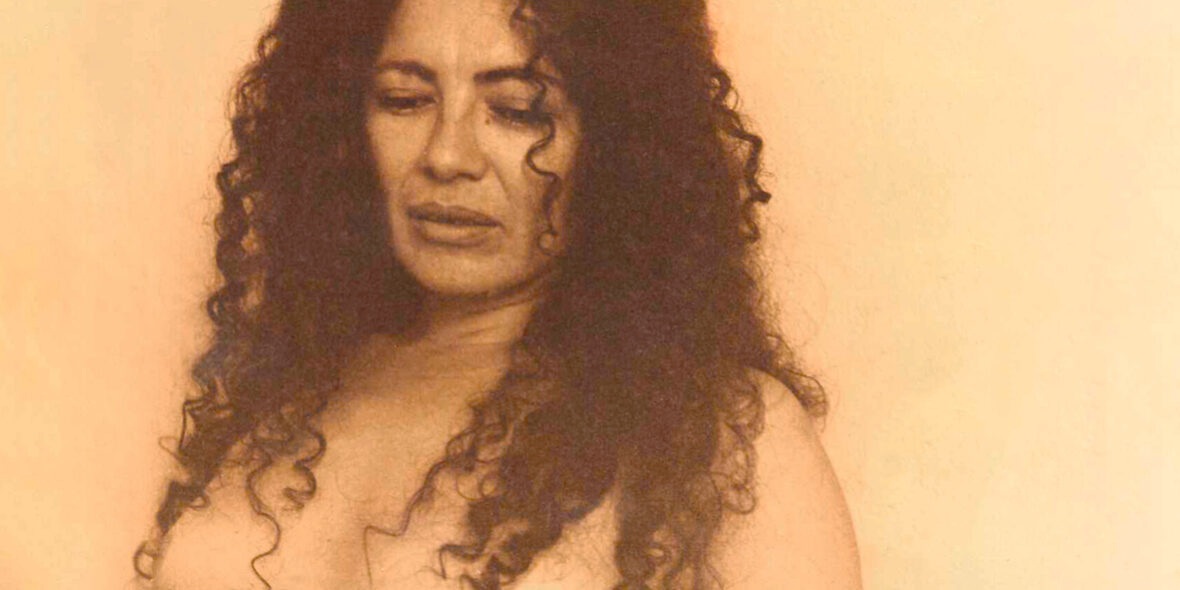

“She was short, dark-haired, and had curly hair. That’s why we called her Cordero,” Marcelo Iturbe told Alexis Oliva, the journalist who reconstructed Avendaño’s life. And who, based on testimonies and archives, also reconstructed a series of emblematic struggles that make up this activist’s biography in “Everything Power Hates” (Recovecos Publishing): the story of “La Negra,” “Vivi,” and so many other affectionate nicknames.

Iturbe is another former political prisoner who was a member of the Revolutionary Workers' Party (PRT-RP) and the Guevarist Youth. It was with this organization that Viviana was arrested for the first time. She was 16 years old, a year before March 24, 1976, when she and two companions first stole a car and then red paint. They needed all of this to commemorate Che Guevara's death. "Forgive me, but we need the car. Don't report it for two hours, we'll give it back to you," Viviana said. And later, when they arrested her, she warned the police: "We're not common thieves." That's how she became the youngest political prisoner, as Oliva's book recounts.

Detained in the D2 (Córdoba Police Intelligence Department), it is said that from the punishment cells she would sing: “Cold tomato juice, you must have it in your veins.” “Where have you ever seen a girl from Villa El Libertador like rock instead of cuarteto?” Norma San Nicolás, a now former political prisoner and member of the Peronist Youth, shouted at her. Her testimony is included in the book. “She was always a rocker, with a strong Afro, and sometimes she wore a headband. She was the youngest political prisoner.” Viviana was transferred to Penitentiary Unit No. 1 and later to Villa Devoto, in Buenos Aires.

There she had her first lesbian relationship. “She fell deeply in love with a fellow inmate with whom she shared a cell or a cellblock. They, who were members of the JG (Youth Guerrilla), informed their leadership in prison that they were in love and in a relationship, and the PRT (Revolutionary Workers' Party) leadership separated them. One went to one cellblock and the other to another. And they didn't see each other again for several years. That later led her to that secretive approach, never speaking about her relationships,” shared Klaudia Korol, former leader of the FJC (Communist Youth Federation) and the PC (Communist Party), one of the architects of the party's revolutionary shift, and a friend of Viviana's. In those years, homosexuality was seen as one of the things that made them vulnerable, a love that in the hands of the enemy was a tool for extortion. So for a long time they chose silence.

Alexis Oliva's book continued to be written even after it was printed. At a presentation, a woman with a cane suddenly asked to speak and recounted that she had been detained with Viviana in Devoto prison. “Lesbianism was terrible. Among us, it was strictly forbidden. Those were times on the left, in Cuba and everywhere, when they considered you 'sick.' Furthermore, it was a 'moral transgression,' punishable by law. Viviana discussed this, not openly, because there wasn't the space to discuss certain things ,” Liliana Teplitzky said at that event.

“Look at this lesbian giving her opinion like that.”

After spending 5 years and 6 months in detention, Viviana was released on April 6, 1981. She also had a sister, Juana del Carmen Avendaño, who disappeared due to State Terrorism.

She never abandoned activism, but even within the "archaic left," being non-heterosexual wasn't easy. José Bollo, a communist leader and general secretary of the Communist Party of Córdoba between 1995 and 2000, recounted: "In those years, '86 and '87, they condemned her in a low and cowardly way, because they didn't have the guts to say to her, 'Hey, girl, what's your opinion on a certain sexual topic?' It was just hallway talk. 'Look at this lesbian giving her opinion like that.'".

After traveling to Moscow for training, she returned to Argentina and shared her life with Marilén Benítez. She was another great love in her life. Her political adversaries within her group of comrades and friends called them “the lesbians of the Federation.” And if her first relationship had been cut short by a political decision, this one was interrupted by Marilén's death in 1989.

“One of the first in the Communist Party to come out as a lesbian.”

At that time, Viviana was not well-liked in some circles because she stirred up a lot of debate and broke with the established norms of communist tradition. "In reality, she wasn't breaking anything: she was revolutionizing in order to bring about change," Bollo said for Oliva's book. Isidoro Gilbert, in his book * La Fede – Alistaándose para la revolución* (The Federation – Getting Ready for the Revolution), explains it this way: "In the FJC (Communist Youth Federation), they sometimes turned a blind eye to the existence of gay women, but they tried not to promote them within the organization."

Although the dictatorship had ended, the punishment of non-heterosexual identities remained in effect. This weighed even more heavily on Viviana when she chose to make her lesbian sexual identity visible. She then had to pay the price of being marginalized within the political and party sphere. “She was one of the first within the Communist Party to come out as a lesbian. That was another transgression within that still dogmatic culture,” says Claudia Korol in the book. And Viviana not only spoke about it, she also actively advocated for it. In 1990, Viviana publicly embraced her sexual identity and began her activism in the lesbian feminist movement, Oliva recounts.

The comings and goings, the agreements, and above all, the disagreements and rejections from the party regarding her lesbian identity, as well as the loves and heartbreaks, led Viviana to San Marcos Sierra. Her biography includes other women with whom she became involved, such as María Alejandra, Verónica, and the woman who practiced Santería with whom she moved in while lending her apartment to a friend who was HIV-positive, until Laura Lucero arrived. Several months before meeting her, in 1999, Viviana, along with a group of activists, had founded the Juana Azurduy Popular Educators Center in Villa Carlos Paz. Following this experience, she traveled through the Chaco forest teaching literacy. Later, at a Latin American Cooperation Meeting, she met Laura.

Viviana, picket line

With the new millennium, Viviana's life seemed too quiet, until a new opportunity for activism arose: defending the unemployed of Cruz del Eje. She began to occupy the white tent of protest, until one day, amid rumors of a road blockade, the media arrived. There was no one to speak. Viviana had gone with Laura and asked what demands they wanted to make. She shared them aloud, and concluded with the power that came from so many years of activism: "We will remain in a state of assembly until further notice.".

On June 8, the police cracked down. The next day, many more people returned to the road. Like the head of a hydra, the crowds multiplied. Journalist Alexis Oliva went there to cover the story: “I didn't know her; I saw her at the road blockade the day before she died. I was struck by how clearly she spoke, by the organizing role she was playing.” He didn't get to speak with her. The following day, June 10, 2000, a car accident ended his life and Laura's.

Little filmed material remains of her interventions, but in one video she can be seen the day before the clash. “We are in assembly. We're not going to spend our lives here, staring at each other. Being in assembly means going, seeing what's being done, and meeting again whenever necessary,” Viviana Avendaño roars, wielding the power of words. The human tide listening to her huffs and tries to say no. But she asks them to wait, resumes her speech, and concludes: “The only way to achieve more is to remain in a state of mobilization. And being in a state of mobilization isn't just standing here.”.

Her friend Eugenia Ferrer, an audiovisual producer, remembers her this way: “We were very boisterous. We were always getting in trouble in the community education groups we participated in because we laughed so loudly. That's just how she was, she didn't care about appearances at all. She had a sharp sense of humor that I loved. She could say the worst things while laughing, being sarcastic; it was hard to make her angry.”

“Vivi was the most cheerful, most committed, most visceral and consistent person in her pursuits that I have ever known,” is what Eugenia Ferrer replied when Agencia Presentes asked her about her friend.

“The police killed her! Sons of bitches!” he heard someone shout at the Aurelio Crespo Regional Hospital. “That shout was the trigger for my initial motivation to investigate her death,” Oliva says. From the biography's epilogue, the chronicler recounts that in the days leading up to her death, Viviana was being followed and threatened. And that the political powers and the police in Córdoba knew her history as a revolutionary activist and had labeled her an infiltrator . That word didn't describe her or how they saw her.

José Bollo described her wake: “I remember the gestures, the humility, and the love with which the women of Cruz del Eje took that coffin. They wouldn't let anyone else touch it: 'We'll carry her.' And they wept and spoke of her as if they were talking about Agustín Tosco or Atilio López.” Viviana wasn't an infiltrator; she was a charismatic and powerful leader.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.