Pedophilia in the Church: Trans activist demands that abuser not go unpunished

The trial against priest Emilio Lamas was scheduled to begin on May 7th but was suspended.

Share

By Elena Corvalán

The trial against Father Emilio Lamas was scheduled to begin on May 7th but has been suspended. The Salta Court of Justice is reviewing the statute of limitations defense. Meanwhile, survivors of his sexual abuse have launched a campaign.

The Salta Network of Survivors of Clerical Abuse has launched a campaign against the possibility that the provincial Supreme Court will dismiss the case against Father Emilio Lamas. Lamas is accused of simple sexual abuse and aggravated corruption of minors, based on complaints from two individuals.

The judges of the Salta Court are “deciding whether the priest will be tried in a public trial or will be granted impunity for the acts he committed against two minors in the 1990s,” the Network stated in its campaign, emphasizing that the trial should have begun on the 7th of this month. “What the Court decides will set a definitive precedent on whether the victims of pedophilia by priests will receive justice and whether the priests themselves will be tried like any other citizen for their actions,” they added.

The campaign was launched on social media by Juan Carlos García and Carla Morales Ríos, who reported the priest for acts committed in 1991 and 1994, when they were 14 and 11 years old, respectively, and were active participants in Catholic Church activities in the town of Rosario de Lerma, located in the valleys of Salta. However, as they both emphasized to Presentes, there are at least five other people behind them, also victims of the priest when they were children or teenagers, who are awaiting the outcome of this process before proceeding with their own complaints.

[READ ALSO: Tiziana, a trans girl from Salta: dancing, resisting and growing old ]

While the courts in Salta maintain that there are no major developments in the case, the oral trial against the priest has indeed been suspended. The Salta Judiciary emphasized that it was included in the general suspensions of public hearings decided upon due to the coronavirus pandemic. However, even without Covid-19, the case would not be ready for trial because the Supreme Court has yet to rule on a statute of limitations claim filed last year by Lamas's defense attorney, José Fernández. The Court's president, Guillermo Catalano, only called for a ruling on the matter on April 28.

Carla Morales Ríos is currently in Rosario de Lerma. Due to economic reasons stemming from the pandemic, she had to return to her birthplace. She is observing the mandatory quarantine imposed by the provincial government on those returning to Argentina. From her place of isolation, she and Juan Carlos García conceived the campaign they launched to raise awareness of the possibility that Lamas might obtain a ruling that would exempt him from going to trial.

Juan Carlos still lives in that same town, where he scrapes by "however he can" after losing his job at the local municipality, right after filing the complaint against the priest in 2018. The two tell Presentes about the emotional, physical and even economic strain that maintaining this demand for justice causes them, represented by lawyer Luis Segovia in the lawsuits they filed in the criminal case.

“What makes me angry is that after going through all of this, the trial is suspended. I feel like there’s never any justice for us: for trans women, for poor people, for Indigenous people. And after two years of being revictimized by having to relive so many things, it was like waking up my inner child again, making her go through all of this. It’s not fair,” Carla tells Presentes.

[READ ALSO: Salta: Homophobia in a Catholic school ]

“It makes me remember and feel vulnerable again,” said Juan Carlos, before recounting what he suffered as an altar boy at the parish house in El Alfarcito. Lamas took him there under the pretext of a religious celebration. “He premeditated everything. And then he would mock me, saying, ‘Who’s going to believe you?’ I’ll never forget that laugh, and today I understand that he felt untouchable, that he did whatever he wanted,” he added.

Carla emphasized that the difficulty is greater now that she has to be in her hometown, where it's not easy to endure the stigma. "I was able to fight because I wasn't in the town, because I wasn't singled out, and because I also had a whole support network."

Furthermore, during this time “my body has taken its toll, I have been diagnosed with anxiety disorder, I had a difficult episode last year, I had facial paralysis also last year, I had to go to the emergency room for gallbladder surgery. My psychiatrist and my psychologist say that my body is paying the price.”

Juan Carlos also recounts the difficulties of living in a small town: “At first, it was hard to go out in public. I received a lot of criticism on social media, and that affected me a lot. It was neighbors, people I knew, saying that all I was after was money. It was difficult; they even attacked my mother.”

“Everyone knew what was happening”

Juan Carlos pointed out that, in general, those accused of ecclesiastical sexual abuse seek the statute of limitations to apply "because they know that victims report it some time later, because it's a very hard blow. Imagine, back in the 90s, when priests were idolized, it was difficult."

He emphasized that in his case, he asked "everyone" for help, and no one believed him. Juan Carlos recounts that in 1991, the justice system was aware of what was happening in Rosario de Lerma because he sought help from Juvenile Court Judge Sylvia Bustos Rallé. She responded: "Well, your father didn't want to file a report."

“My father was a working man, a railroad worker, he didn’t have much education, and we were obviously poor, so he thought: facing all this is going to be very difficult,” Juan Carlos explains. At the end of his life, he asked for forgiveness and encouraged him to report the abuse so that he could “continue seeking peace.”

“One way or another, the justice system knew that this priest had raped me and that he was committing crimes not only against me, but also against other boys. Because Emilio Lamas raped five boys here in Rosario de Lerma.”

This campaign is for people to express themselves and for "the justice system to see that they are not alone behind four walls when it comes to voting, but that an entire society is watching them to see what verdict they will give."

Justice is collective

Carla and Juan Carlos share the experience of having been born into Catholic homes. Their mothers are devout believers and brought their children to church. These mothers also had to make a great effort to separate their beliefs from the ecclesiastical institution.

After Juan Carlos García reported Lamas, Carla's mother made public statements about the abuse her daughter had suffered 25 years earlier. "She has gone through a whole process to be able to speak out, because if it hadn't been for her, I wouldn't have spoken," Carla said. That's why she feels that "she also hopes for justice."

For Carla, the only time there was justice for trans women was in the ruling against the transphobic murder of human rights defender Diana Sacayán. That was a collective achievement, and now both Carla and Juan Carlos understand that their cause is also greater than a personal action.

“I believe that what I do isn’t just for me; I think it’s for many people. Many girls write to me all the time, especially when I stir things up with this issue. Many of them can’t speak out, or they don’t speak out because their abuser has already died or is still in the family, and so they feel that their fight is intertwined with mys. I would love to tell them to speak out, but each one has her own process. It took me 25 years to be able to speak out, it took me more than ten years to realize the abuse, and it took me more than 16 years to convince my family.”

Pressures from the Church

Juan Carlos insists on how difficult this process is, and highlights the persecution he suffered within the Church itself, “to keep me from speaking out, to make me leave the Church, it was very hard”; they even received a visit from Bishop Julio Blanchoud. “It was difficult for me to have a monsignor come, for my mother to leave the meeting crying, saying, ‘Let’s not get involved with the priests.’ She’s illiterate, old, and sick, so it’s painful, I can’t leave it like this.”

She said she doesn't want other victims to "go through what I went through." That's why she tells them it's okay if they don't want to "come forward," but she insists they file a report. "I tell them, prepare yourselves, because you have to report it, otherwise the truth will never come out and you'll be like this, one day good, one day bad, one day happy, one day sad."

Alone but together

Carla emphasized that when they conceived this campaign, organizations contacted her to offer their support. “But my trans community and I have learned to raise our own voices, because I don't like being controlled, and when I speak, I speak from my trans identity, from my poverty, from my Indigenous identity, from my experience as a cannabis user, from my abortion rights, from my feminist perspective. I don't know if all those organizations that want to support us actually want someone who speaks on these issues. Since colonization, our people have always been the ones who have suffered, always the ones who have been denied justice. And the Church is complicit in that colonization.”

Juan Carlos also understands the power of the Church, and believes that the outcome of this case is crucial in encouraging other victims to demand investigations into the crimes they suffered. “They also depend on my case to come forward, so I also feel that responsibility, which at the same time strengthens me because I am not alone.”

And he added that if they receive an unfavorable ruling, they will seek "more resources to continue fighting, because the only way I have today is to keep fighting because it's not just my case, now there are these other kids waiting and I'm using my last resources."

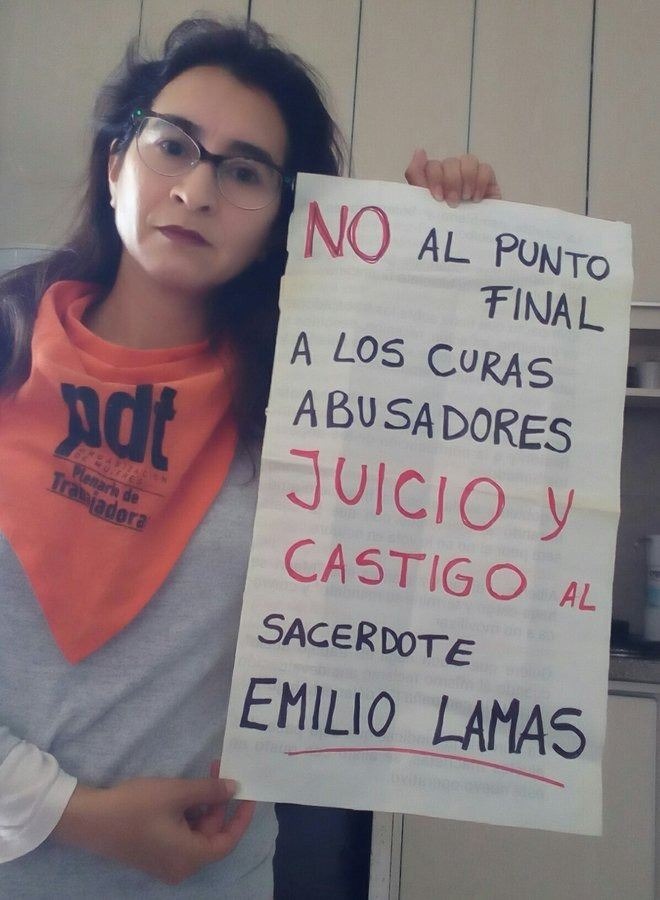

Gabriela Cerrano, a leading figure in Salta for the Plenary of Women Workers, warned that “a ruling in favor of Lamas would set a dangerous precedent, preventing priests in Salta with cases dating back more than 20 years from being brought to justice. A ruling in favor of the victims would be a step forward in the fight against impunity within the Church.” Cerrano recalled that the Salta courts have already ruled in favor of priests accused of sexual abuse. Judge Adolfo Figueroa, of the Fourth Chamber of the Appeals Court, overturned the indictment of Father Agustín Rosa Torino. Days later, he ruled that the statute of limitations had expired in the abuse cases against Mario Aguilera, the current chaplain of the Catholic University of Salta.

The Network's campaign invites users to publish actions and statements using the following hashtags:

#NoToTheFinalPointOfTheCaseOfFatherLamas #JusticeForTheVictims and #NetworkOfSurvivorsOfClericalAbuseOfSalta

All our content is freely accessible. To continue producing independent, inclusive, and rigorous journalism, we need your help. You can contribute here .

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.