Journalism, Covid-19 and vulnerable groups: 5 recommendations

Report of the panel 'COVID-19 and groups at risk: indigenous peoples, migrants, LGBTI populations and sex workers', within the framework of the Virtual and Hispanic American Forum of Scientific Journalism organized by Factual.

Share

By Airam Fernández

How did calls for help from women victims of domestic violence skyrocket during the Covid-19 lockdown in Latin America, forced to live with their abusers in a region where the average number of femicides exceeds ten per day? How do trans people and sex workers survive on the streets while the majority of the population spends quarantine in virtual workshops and meetings and sheltering at home? What kind of difficulties do Indigenous communities face, isolated in areas without health services, or vulnerable migrants facing border closures, who, in addition to maintaining their own livelihoods, also provide financial support for their families in their countries of origin, and who now face the added burden of high unemployment rates resulting from the crisis?

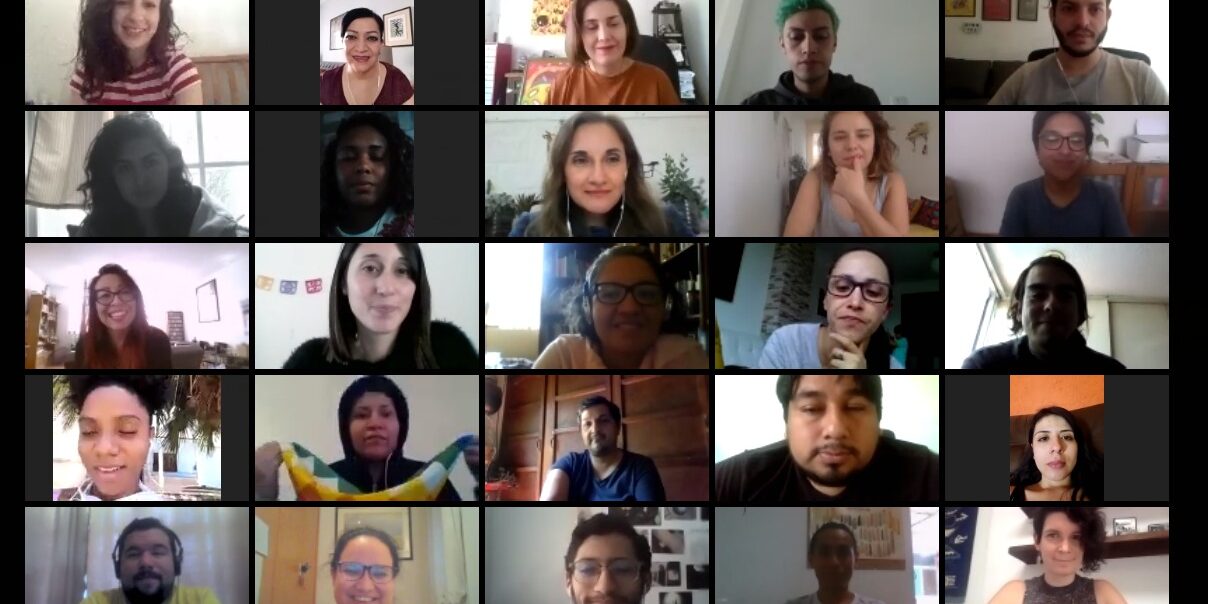

These were some of the topics discussed in a panel featuring Presentes, as part of the Virtual and Hispanic-American Forum on Science Journalism organized by Factual, entitled 'COVID-19 and at-risk groups: Indigenous peoples, migrants, LGBTI populations, and sex workers'. It was a panel of women journalists, convened to propose coverage and narrative strategies and to reflect on the role of journalism in relation to these vulnerable groups, who have historically had little space in mainstream media.

The conversation was moderated by Colombian journalist Ginna Morelo and had space for more than 100 participants. For an hour, everyone listened attentively behind their screens to the contributions of journalists and editors from Argentina, Peru, Mexico, and Chile: Ana Fornaro and María Eugenia Ludueña, co-directors of Presentes; María Isabel Torres, director of Mongabay LATAM; Eileen Truax, a journalist specializing in migration; and Nataly González, national advisor to the Chilean Journalists Association.

[READ ALSO: Coronavirus, rights and journalism: Presentes' commitment ]

Each of them briefly described the situation of these groups in the countries they cover and how governments have responded to address their needs. Argentina is the only country that has an advantage, being at the forefront of progressive laws for sexual diversity, said Ana Fornaro: “This is an atypical case: we have a Gender Identity Law, Equal Marriage, and Trans Employment Quotas in some provinces, and this means that at an institutional level, these groups are given greater consideration during the pandemic. That's why we see a huge disparity compared to other countries. In Central America, for example, there are no measures, public policies, or specific support whatsoever, and not only that, but these groups are subjected to state violence.”

When the Chilean government announced the first phased quarantines, local feminist movements began discussing how confinement could affect women in their homes, especially those who are daily victims of domestic violence. As a result, the authorities took some measures. “This issue is on the agenda thanks to women and social movements; it was never raised by the government. Furthermore, we didn't have a minister in the Ministry of Women because the previous one resigned in March. And the one who arrived recently is facing a lot of criticism,” said Nataly González.

In the United States, President Donald Trump's anti-immigrant policies have affected women, children, and entire families in recent years, and that hasn't changed with the pandemic. This is one of the concerns of Eileen Truax, who, although Mexican, lives and works in the US. But the journalist recognizes a key strength in addressing the crisis: the governors' management capacity, although in most cases, the responses depend on their political affiliation. "We've seen very different, sometimes very opposing, reactions depending on the state. Democrats have been the ones who have responded most quickly and effectively," Truax explained.

[READ ALSO: Two webinars from Presentes on journalism and coronavirus ]

María Isabel Torres emphasized that the region's states and governments are overwhelmed by the pandemic. For this reason, she believes the lack of support for Indigenous communities is more pronounced, and their vulnerability is consequently greater: “It is very difficult to find specific figures on Indigenous people with the virus. The figures we have come from the organizations and representatives of each community, which demonstrates that there are few connections with the government.”

Despite the contributions and work each participant makes through their media outlets and organizations in the countries they cover, the conversation reflected how much work remains to be done and how much reflection is needed within newsrooms on these issues. Below are a series of recommendations gathered throughout the panel on how to address the crisis with coverage designed from a human rights perspective, offering innovative, insightful, and contextualized narratives to audiences:

1- Listen to all complaints and amplify them

Ana Fornaro recommends that the grievances of sexual diversity be heard and amplified in the media agenda as part of the gender agenda: “While the issue of violence against women is extremely important to make visible, it is not the only one. In general, what happens to sexual diversity, trans people, or sex workers, who are the most vulnerable groups right now because they live hand to mouth, because they have been evicted from their homes, and because they also suffer institutional violence, is not covered.”

María Eugenia Ludueña added that, these days, prisons are spaces far removed from the journalistic spotlight and where greater irregularities and human rights violations can occur: “They are not being covered with the required complexity and there are many reports of violations coming from these spaces,” she warned.

Social media platforms are also important tools and channels for reporting abuses. “Many Indigenous organizations even file their complaints through these channels. These are channels we cannot ignore, even though the virus is out there,” suggested María Isabel Torres. However, she emphasized the importance of using them responsibly to avoid spreading false accusations.

2- To make the true protagonists visible, to change faces and to debunk myths

In migration issues, women are often rendered invisible, said Eileen Truax. The reason is that most coverage is based on myths: “In the images that appear in the media of migrants crossing the desert or walking to get from one country to another, it’s usually men who are seen. Women rarely appear because there’s a widespread feeling that migration is a male phenomenon. The idea of family reunification also persists, the notion that the man goes to work and the woman will join him later.” But nothing could be further from the truth: 48% of migrants worldwide are women, and more than half are heads of household, Truax said. Based on these points, one of her recommendations is to seek out women’s faces and voices when telling stories, to highlight the important role they play in sustaining two economies and contributing to the workforce of both their country of origin and their destination.

Truax also proposed investigating the occupations and origins of these workers. She backed up her argument with figures: in the US, there are two million farmworkers, and 75% of them are migrants. Three out of every four farmworkers who work to put food on the table weren't born there, and many lack documentation and the means to regularize their status. Of this percentage, an estimated 6% are Indigenous . “So you see: they are migrants, sometimes undocumented, women, and also Indigenous. This reveals layer upon layer of vulnerability, and these stories go untold. So I think it's very important to diversify the image of migrants in all their diversity,” she suggested.

Added to this group are the children of migrants, known in that country as Dreamers : young people who arrived with their migrant parents and are now around 20 or 30 years old. “The issue is that they only know this country; they’ve always been here and have an irregular immigration status. Many of them have already gone to university, specialized in some area, and are playing essential roles in the pandemic. However, they only have temporary protected status,” Truax explained.

Torres insisted on rethinking how Indigenous issues are covered, because the strategies typically employed often contribute to their invisibility, even unintentionally. In her view, the mainstream media has failed to do well in referring to "Indigenous peoples." It's a concept that is "too broad," she said, because within these groups there are countless communities and ethnicities: "To lump them all together under that single concept, in a way, makes invisible all the possibilities for telling their stories. For example, we have Indigenous communities in remote areas, or those near cities that struggle to access food, or students in cities who are stranded and unable to return to their communities. And let's not forget that these are all different communities, already threatened before the pandemic, living in highly vulnerable situations, with assassinated leaders, land invasions, and illegal mining, to name just a few of their problems."

3- Take special care when covering sex work and women victims of violence

In Argentina, there's a very strong debate between sex work and prostitution. "They're like two distinct schools of thought," Ludueña clarified. At least from Presentes' experience, she's seen that only some transvestite and trans people choose and can be in the first group, "but the majority are in prostitution, and frankly, it's the only work they can access to survive. This creates a very complex situation regarding support, starting with the fact that they don't experience quarantine in the same way as other people," she explained. In these cases, her advice is to never report isolated cases to avoid falling into stereotypes or "reductionist views" of these roles. "Telling the stories, not the individual cases, is what will work best, especially in a situation as complicated as the one we're living through, where institutional violence is the first thing that comes to light," she says.

Nataly González believes it's very easy to fall into these stereotypes with this type of coverage in the region because most countries lack a legal framework for sex work. Therefore, journalistic perspectives must be very careful: “In a context where sex work is neither prohibited nor recognized, these groups are excluded from any possible institutional benefits and, moreover, exposed to sensationalism or the reductionist views we often see in the media.”

González added that in no case is it advisable to take the testimony of women who are experiencing episodes of violence, specifically right when that violence is occurring, first for the safety of the victims and second for a matter of ethics: "Those testimonies are taken when we see that they overcame it and managed to survive and that is when they are truly a contribution to the work we do."

4- Having diverse sources

Social organizations are the primary sources for Presentes, and collaboration with them has always been crucial. “But now it has intensified considerably, and they are key to our daily coverage,” said Fornaro. They are also indispensable for the work of a media outlet like Mongabay, added Torres, especially now, when going into the field or covering a story in an Indigenous community puts them at risk. “That’s why it’s necessary to activate a large and diverse network of sources and rely on the people in their communities, their leaders and representatives, so that we can compensate for our lack of presence in the field,” she noted.

Torres also said that we shouldn't forget that governments and authorities are also necessary sources: “Even if we already know that they won't tell us anything about a certain issue or that their strategy is not to respond, it's important to try. Writing that down in a note is also information.”

Changing the narratives

For Truax, the Covid-19 crisis is a perfect opportunity to change the media narrative and shift towards one that respects the dignity of these vulnerable groups. “ We have a great opportunity for mainstream media and political leaders to stop referring to them as enemies, culprits, invaders. But the big challenge is how we break down that barrier of otherness and how we establish a collective 'us ,'” she said. Her recommendation is to emphasize the stories of people who have already experienced vulnerability and overcome it: “In the US, Dreamers or established migrant women with positive life stories are perfect for this.”

Ludueña outlined the approach of solutions journalism and the search for stories with three components: resistance, struggles, and networks: “We see that trans people are the most affected by the pandemic, but they are also among the most active in generating resistance and solidarity within their community, whether by collecting money, food, or opening shelters.” And Fornaro added: “Many activists are working tirelessly to bring food to people who are truly going hungry. That is also admirable and needs to be given more visibility.”

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.