LGBTI+ incarcerated population denounces lack of protection against COVID-19

LGBTI+ pavilions in various prison complexes denounce the lack of supplies to deal with the pandemic.

Share

By Alejandra Zani and Verónica Stewart

Photo: Ezeiza Prison/Judicial Information Center

LGBTI+ wards in various prison complexes are denouncing the lack of supplies to cope with the pandemic. A report by RESET details the discrimination and specific risks faced by this population.

At the Ezeiza Federal Penitentiary Complex I, Emiliano Santa Cruz (34 years old) spends his days with 21 other gay men in Pavilion A, designated for the LGBTI+ prison population. “We were without cable and phone service all weekend, which led to confusion. We thought they were trying to misinform us about what's happening to our friends in Devoto,” he told Presentes.

On April 24, a security guard at the Villa Devoto Penitentiary Complex tested positive for Covid-19. The news generated enormous concern among the inmates, who had been demanding basic supplies for personal hygiene and cleaning. This sparked a riot that resulted in several injuries and the establishment of a dialogue table between various authorities, human rights representatives, and delegates from the different cellblocks. Finally, this week, coronavirus testing began for the inmates.

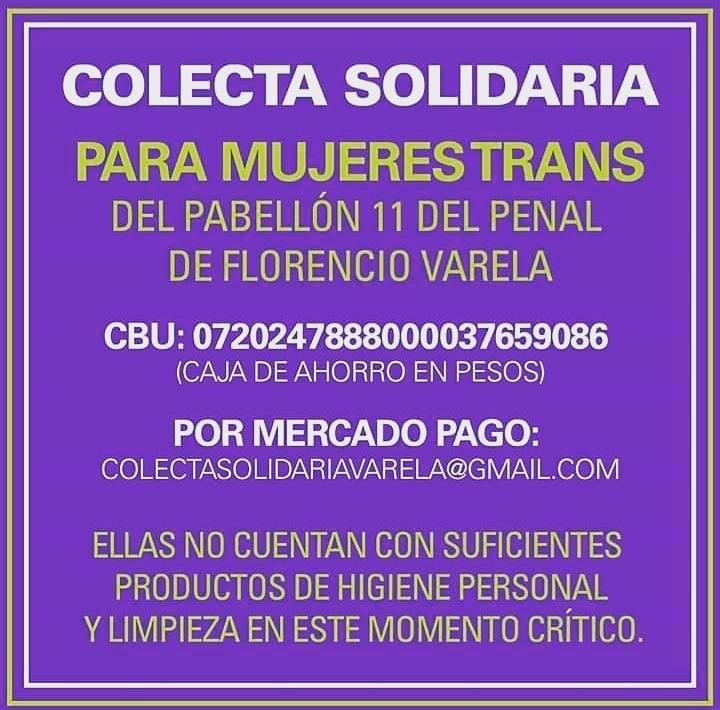

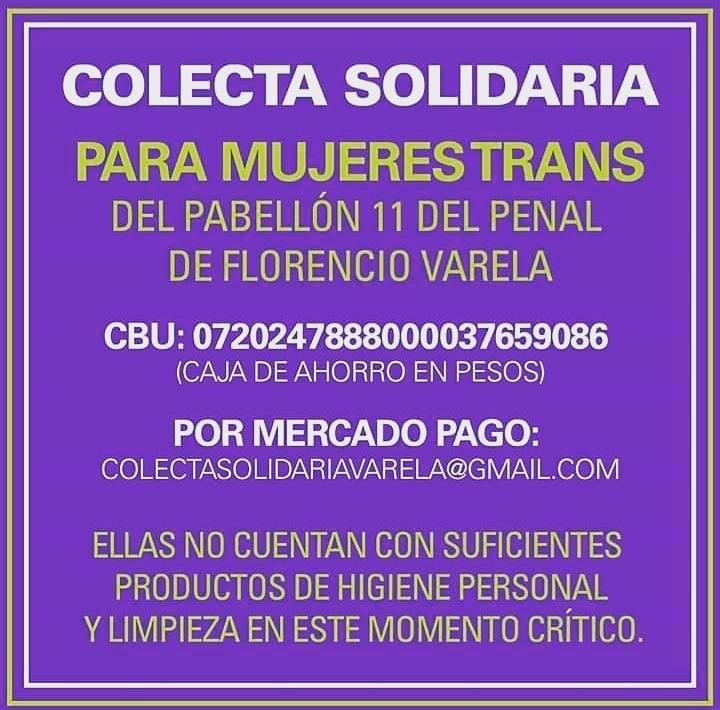

[READ ALSO: Covid-19: Transvestites and trans people denounced as abandoned in prisons in the province of Buenos Aires ]

“I called the Devoto prison wing because I was worried about some friends, and they told me that some guys were already infected with the virus. They quarantined the whole wing because there aren't any individual cells there. They gave everyone gloves and masks, and everyone was tested. But between the city tests and the prison tests, by the time the results come back, it'll be a bit late. What's happening with the coronavirus in prisons is a ticking time bomb,” says Emiliano. So much so that the guys in Wing A had to organize themselves to pool their meager earnings—the wages they receive for their daily tasks—and invest it in bleach and other hygiene supplies.

From the National Penitentiary Ombudsman's Office, Josefina Alfonsín, who is also a member of the Commission for Luz's Acquittal , affirms that inmates have decided to denounce the irregularities and the situation they are experiencing. “They are eager to tell their story about the situation in prison, which is currently extremely delicate since the riots began in Devoto and spread to other prisons as various protests. We know that this situation brings more violence and repression,” Alfonsín explained to Presentes.

"Gays Deprived of Their Freedom" was launched, where inmates from Pavilion A of Ezeiza prison denounced the lack of personal hygiene supplies: bleach, detergent, and laundry soap. They also complained about the poor quality of the food and the constant discrimination they face from the guards. "The situation is worrying and stressful. When they found out about the page, we magically managed to get yerba mate, sugar, and even cookies. I was surprised. The heating, though, hasn't worked since last year."

The goal of the fan page is to raise awareness about the existence of an LGBTQ+ pavilion at Ezeiza prison and to show what happens inside. “No human rights organization, no LGBTQ+ organization, has ever come to offer us any help, to get to know the gay men deprived of their freedom, because not all of us here are the same. There are different stories, and they shouldn't lump everyone together because this isn't television; we are people, and we have rights.”

Trans women in Ezeiza prison

“Since the riots began in Devoto, we’ve been expecting a heavy-handed crackdown from the prison system,” says Dalma Emilce Lobo (40 years old), a trans activist currently incarcerated at the Ezeiza Federal Penitentiary Complex I. “ Here, I’ll always stand with my fellow inmates, never with the police. I’m imprisoned for being trans and for working as a sex worker. Almost all my fellow inmates are here on trumped-up charges or for drug dealing. We’re demanding that they guarantee our health; we don’t want to die in prison.”

In 2000, Emilce was accused of attempted robbery and spent eight months in prison until she was released due to lack of evidence. In 2007, she was detained in Marcos Paz, where she lived in a wing with people accused of rape and indecent assault. There, she and nine other trans women organized to report the various rapes and sexual extortions that prison guards demanded in exchange for food, and they succeeded in having them transferred to the gender-segregated wings in Ezeiza.

“I am a survivor of the Argentine prison system. I live with HIV, a lung nodule, and I am awaiting house arrest.” According to Emilce, the necessary testing is not currently being done in Ezeiza. “ Isolation in this place is impossible. The dining room is a two-meter-wide hallway, the kitchen and bathroom are breeding grounds for infection, there are nine of us trans women in one room, and they give us half a liter of bleach for all of us. The windows are broken, they don't come to fix them, and they don't let our families in to drop off our food. A few years ago, there were people with asymptomatic tuberculosis, and they only realized it when they started coughing up blood and had to be transferred. The virus isn't going to come in through the window here, my dear.”

At-risk population

Emilce is not the only one awaiting house arrest. In the context of the current health crisis, many of our fellow inmates with pre-existing health conditions are in need of it . A new report presented by the Gender and Sexual Diversity Team of the National Penitentiary Ombudsman's Office, along with other regional organizations, estimates that Argentina has seen an exponential increase in the incarceration of trans and travesti women. “The latest data presented by the National System of Statistics on the Execution of Sentences (SNEEP) reveals a growing criminalization of this group under Law 23.737, showing that seven out of ten are incarcerated in the Federal Penitentiary Service (SPF) for violating drug laws. By the end of 2018, 76% were detained without a final conviction, which is extremely worrying,” the report explains.

[READ ALSO: Report: Transvestites and trans people in Argentine prisons: more migrants, young people and without convictions ]

On April 27, the activist organization RESET – Drug Policy and Human Rights – filed an amicus curiae brief , a legal tool that allows those not directly involved in a case, but whose input is valuable (as is the case with several human rights organizations), to participate. In this instance, the document seeks, among other things, to “consider the trans and travesti women community as a particularly vulnerable population in the face of COVID-19, within a generalized context of overcrowding, overpopulation, and a humanitarian crisis in Buenos Aires prisons.”

According to this petition, the most frequent health problems suffered by the trans and travesti population are “a history of tuberculosis, complications arising from the use of industrial silicone, or some chronic illness.” The situational analysis report for the period 2018-2019, “ Trans and Travesti People in Incarceration, ” prepared by the organization Otrans, records that 73.3% of the trans and travesti population in prisons in the Province of Buenos Aires suffers from some type of illness. The most frequent, representing 59%, is HIV.

Regarding medical care within prisons, the report denounces a lack of supplies and medical personnel, so a large number of inmates are forced to resort to hospitals outside the prison walls. “What happens in prison is that any over-the-counter medication, such as Ibuprofen or Tafirol, ends up being used to treat complex conditions like tuberculosis,” Aramis, a lawyer and activist with RESET, explained to Presentes.

House arrest

Obtaining house arrest is not so simple. On the one hand, as Aramis explains, many judges are not working regularly due to the pandemic. On the other hand, “the issue of house arrest is tied to access to housing, to the same difficulties in obtaining it,” Aramis adds. “Generally, the homes where raids take place are where they lived.” Therefore, it is usually friends who offer their homes so that those deprived of their liberty who need it can obtain this benefit. As the RESET report details, “the vast majority of trans women and transvestites have to overcome enormous obstacles to access housing.”

[READ ALSO: Court orders to maintain an exclusive pavilion for gays at Ezeiza prison ]

Another major problem facing the prison population in this context is the ban on visits. Given the lack of supplies from the prisons, it is the inmates' close relationships that fill the gap. Thus, it is the leaders of the LGBTI+ cellblocks and human rights organizations that bring in the necessary supplies. "These aren't things they provide us inside the prison," Crystal (36) explains to Presentes. On April 20, after complications from a silicone injection, Crystal was granted house arrest, which she is serving at a friend's home. "In the cellblock where I was, there were 64 of us, but with everything that happened, many women were released. There were 23 infected with HIV," she adds.

[READ ALSO: The IACHR calls for respect for LGBT+ rights in the context of Covid-19: 5 recommendations ]

The usual delays in processing cases also prevent those who need it from receiving adequate medical treatment. When there is no one demanding that these processes be expedited from the outside, cases move even more slowly. As RESET details in its amicus brief, “the vast majority of trans and travesti women detained in the province of Buenos Aires are South American migrants, they don't usually receive visitors, and their communication and interpersonal networks outside prison are extremely limited, which accentuates the delay in accessing rights such as parole, temporary release, or house arrest.” Regarding this, Aramis tells Presentes that “along with other friends and activists, we submitted the cases of ten women to grant them house arrest, which they hadn't yet requested. If there's no one monitoring the situation and demonstrating that what happens matters, this is what happens.”

Discrimination, a recurring problem

Despite being in a gender-segregated wing, Emilce explains that discrimination is far from over. “Here, we’re discriminated against by the guards who say things like, ‘Where are the boys? What a smell!’ every time they walk by, while the bigwigs outside gloat about bringing us to a divine prison. Then the journalists are surprised when they see a hidden knife. What do they expect? That we’ll let ourselves get killed in a riot? Here, we have to defend ourselves against the violence of a system that constantly mistreats us.”

RESET's amicus brief "the violation of the right to gender identity, the imposition of cis-sexist regulatory prohibitions in the visitation regime (which only take into account the traditional and biologically constituted family), in the use of clothing or cosmetics, in recreation or in access to work, education and health, and the exercise of violence by prison staff in transfers, in searches and during the stay in confinement are some of the problems denounced in the provincial, national and international judicial sphere."

[READ ALSO: COVID-19 – CAMPAIGNS: HOW TO HELP ]

In Ezeiza, Emiliano recounts, pavilions A and B are “the ones for homosexuals.” “Pavilion B is for foreigners and people over 50. They started a strike because we were without water for several days. Imagine not being able to flush the toilet for three days, not being able to mop the floor… Anyway, we had to talk to the warden, who luckily is flexible. They came here to give a course on how to treat us, but the course was discriminatory. We were laughing, saying things like, ‘ Faggots breathe, drink milk, drink coffee,’ what did they teach in that course? It was useless; they continue to insult us for our sexual orientation or our gender identity.”

Regarding Pavilion A, Emiliano explains that the prison service doesn't treat them properly. “They tell us we're fucking troublemakers, that because we're gay we commit this or that crime, and that we come here to cause trouble. I'm about to finish my sentence, and the prison officials don't know each of our stories; they're not there to judge us, that's what the justice system is for.”

All our content is freely accessible. To continue producing inclusive and rigorous journalism, we need your help. You can contribute here .

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.