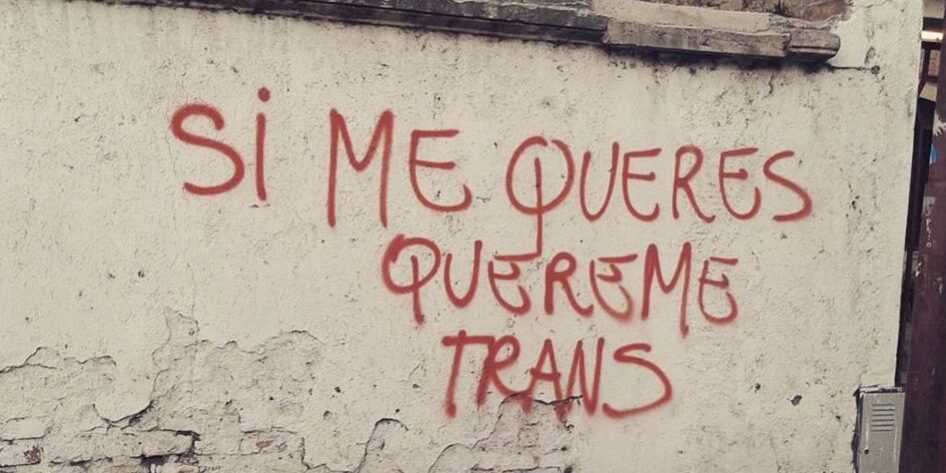

What is it about love for transvestites and trans people?

One of the first and most tormenting fears after my transition at age 15 could be summed up in one question: Will anyone love me like this?

Share

One of the first and most tormenting fears after my transition at 15 could be summed up in one question: Will anyone love me like this? I couldn't even define myself as transvestite or transgender; I had no idea what those terms meant. Almost 16, I started going out dancing to parties organized by the schools in my neighborhood, mostly in halls where I went with another friend who, for one reason or another, was also marginalized: because she was fat, because her parents were separated, because she was considered ugly, etc. I, a queer girl, protected her through my quirks: high platform shoes, black clothes, colored hair, makeup.

In the late 90s, in the greater Buenos Aires area, that wasn't easy at all. It was a very lonely path where even the gay guys I hung out with set limits: "It's fine if you come to my house, but if you come, come as a kid... because of my parents, you know..." Something like: it's fine that you're gay, a freak, but the limit was no longer being seen as a kid. And back then, I was a transgression in the neighborhood, an abjection. And, like everything abject, it generated a point of escape, a threatening desire.

[READ ALSO: What we talk about when we talk about trans love ]

I fell madly in love with everyone except myself: with my older brother's friends who came over, with schoolmates, with the caress someone gave me while I was giving them oral sex, with the repressed kiss some young man gave me in a corner, the same one who would later yell "faggot" at me when he was hanging out with his friends, and so on…

The whole world was beginning to tell me specifically that love in terms of erotic-affective relationships was only for those who best adapted to binary thinking, to cis-sexuality, to heterosexuality.

At that time, I also felt that deconstructing the masculinity imposed upon me placed me within femininity. And I necessarily understood that femininity as becoming a woman, and womanhood had only one way of being and existing. A woman couldn't have a trace of facial hair, she had to be hairless, have moderate curves, she had to sleep only with men—womanhood and all its mandates created in the image and likeness of and for another, a cis man, of course.

My appearance "helped" me pass as a girl/teenager since I was very thin, had long hair, features typically considered feminine, etc. That gave me a certain guarantee of "success" with men; some even started telling me, "To me, you're a woman." I felt incredibly accomplished.

At 18, I started a friendship with Javier, who was the same age as me. He was drawn to my quirky femininity; I found his every move erotic. He was one of those muscular, dark-haired guys with an immaculate face. We'd spend entire nights in my room listening to music and talking. I'd dress up quite a bit for our time together, using foundation to cover the shadow of my upper lip, justifying it by suggesting he might have some kind of heterosexual, binary expectations. But at the same time, I openly said, "Whoever loves me has to love me for who I am, beyond the hormonal traces." Nevertheless, the whole world kept telling me that those traces had to be erased to belong, even to be accepted into someone's heart, because otherwise... fine, but just friends, and secretly. I don't quite know how, but I do know where and when we fell in love and began a "relationship" that lasted 11 years. A privilege? Back then, I was starting to suspect it was. Today, I could say so.

"Let someone dare to live with us."

Lohana Berkins was asked the following question in an interview: What would you want in a life partner? Lohana replied: “First, that someone would love me sincerely. And that they would love me, love us, for who we truly are. That's a step I think this society still needs to take, that we aren't just consumed by prostitution, but that someone dares to live with us. Love is very difficult, and it's a topic we don't talk about much. First, I would like someone like that, someone who falls in love and makes you feel divine.” Hearing those words, seeing her expression as she answered, was undoubtedly one of the driving forces behind my activism, particularly in terms of my own and our sexual and emotional relationships. “Every bond is political” and from that point we begin to incorporate the concept of “emotional agenda”, absent from the rights agenda and which undoubtedly affects a way of being and being with others, how we are seen and felt by others.

In the case of love, we can now say with certainty and evidence: “heterosexuality has failed,” certainly not only by reducing it to sexual practices, but also by broadening the concept to a way of creating bonds, ties that organize a society in erotic-affective, economic, political, and cultural terms. And from these ways, I take away that at least we transvestites and trans people saw them from the outside, from a position of absolute powerlessness.

[READ ALSO: What we talk about when we talk about trans beauty ]

“And I’m not talking about putting it in and taking it out, and taking it out and putting it in only, I’m talking about tenderness, my friend. You don’t know how hard it is to find love under these conditions, you don’t know…”, Pedro Lemebel read as a speech at a left-wing political event in September 1968.

As Lohana Berkins also told us: “Transvestites are the illicit desire of the capitalist right. When will we be the legitimate desire of the revolutionary left?”

Wanting and getting paid

Talking to a trans friend, she told me, “Guys are awful, girl. I just chose to get money from them. What else can they offer us?” That led me to delve a little deeper than the perspective that labels us as “sex workers” or “in situations of prostitution.” It’s not just about economic exchange, comrades. In the relationships we establish with clients or those who buy sex, there’s often affection, caresses, glances, hugs, falling in love, confessions, shared loneliness. This doesn’t mean that the same can’t happen to a cis woman, but unlike us, these expressions of affection don’t happen in public spaces.

The figure of the "freeloader"—the one who doesn't get charged—is often linked to this. And we don't charge them because we like it, because it makes us feel a little better than the rest, or it might even spark some kind of connection that extends beyond the four walls of our home.

New ways of connecting

There are also the bonds that are established outside of sex work or the situation of prostitution, those that we meet in an assembly, who are deconstructing their hegemonic masculinities and seem much more empathetic.

We are last in line to be loved, always last in line in almost everything, but also in that learning we are getting closer to new ways of relating to others, not only cis-hetero men, but also other trans people, lesbians, gay men, in that sense we are more aware than the cis-heterosexuals who insist and insist on "not opening up".

We don't have enough experience to lecture, but we do have the experience to see from the outside how historical violence is reproduced, deaths in the name of a single model of love (which isn't love). And we're not over it all; we also need to be led by the hand through public spaces, to be kissed, hugged, cared for, and if that hetero-cis-sexuality continues to deny us in some spaces, we'll give them those spaces; we'll find new strategies for surviving heartbreak, we've been used to it since childhood. And if it does appear, forget about Catholic Valentine's Day. We want courage… because that will make us more revolutionary.

]]>We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.