The trial for Azul's murder has begun: "Trans people are in a vulnerable situation"

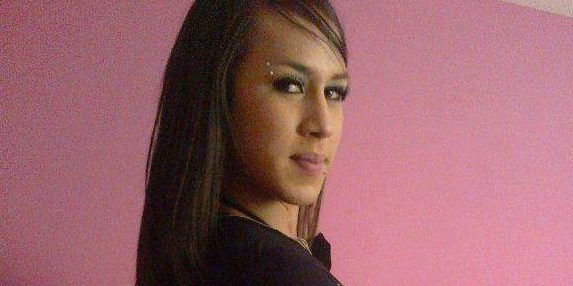

Chronicle of the first hearing of the long-awaited trial for the murder of Azul Montoro, the 23-year-old trans woman who was stabbed to death.

Share

By Alexis Oliva, from Córdoba. With the opening statements from both sides and two key testimonies, the long-awaited trial for the murder of Azul Montoro, the 23-year-old trans woman stabbed to death on October 18, 2017, in Córdoba, began yesterday. The presence of LGBT+ groups and political and social activists in the courtroom and on the street framed the first day, where the issues that will be the focus of the debate were laid bare: the perpetrator's criminal responsibility and the aggravating circumstance of femicide.

“With intent to kill and treachery”

With the courtroom filled with family and friends of the victim, political leaders, activists, and journalists, at 10:20 a.m. on the last day of July, Judge Gustavo Rodríguez Fernández, president of the 9th Criminal and Correctional Court, swore in the twelve members of the jury – seven men and five women – and ordered that the handcuffs be removed from Fabián Alejandro Casiva, 26, accused of “homicide aggravated by gender-based violence”.

The accused, the story, and the reactions

In the presence of the murdered young woman's father, mother, and brother, each of the 17 wounds inflicted on her chest, neck, face, and hands was detailed. It was revealed that Casiva also attacked a poodle in the apartment with the knife and stole the victim's Samsung cell phone. At that point in the account, some members of the public were crying, while others clutched their heads or glared angrily at the perpetrator.

“An explosion of male violence”

Prosecutor Gustavo Arocena emphasized that Azul was “a sex worker who had achieved legal recognition of her identity as a woman” and had lived “a life plagued by discrimination.” “She didn’t know she would meet her tragic end in the red-light district, where she worked,” he said before speculating that “something triggered the defendant’s emotions and behavior, causing him to lash out at Azul.” He then recalled: “It wasn’t the first time he had erupted in an act of misogynistic and sexist violence, even against women within his own family: he had assaulted his mother and his sister.”“Azul was a person who wanted to be included”

Next, the plaintiff's lawyer, Tomás Aramayo, addressed the jury: "It is important that you know how the trans community lives, with a life expectancy of 35 years, without labor or social inclusion, and perhaps the only alternative left to them is sex work."

“He does not understand the criminality of his actions”

In turn, public defender Javier Rojo said that “Fabián Casiva did not understand the criminal nature of the acts” attributed to him, although “the criminality must first be proven.” “Clearly, the evidence indicates that he did not understand,” he maintained. He cited “almost unanimous expert opinions indicating that this person suffered from a developmental disorder,” which “worsened and culminated in the regrettable event of the death of a human being.” Furthermore, the defense attorney stated that it is necessary “to investigate whether this death was because the victim was a woman or was another victim of his mental illness.” In any case, he alluded to the benefit of the doubt: “If there is no certainty that he fully understood his actions, the doubt works in his favor and provides a kind of protection” against a potential conviction. However, he admitted the possibility that “he might be committed to a psychiatric institution.” Fabián Alejandro Casiva refused to testify about the incident. In the initial identification questioning at the start of the trial, he said he lived with his parents and five other siblings, completed an accelerated high school program up to the third year, worked in the parking lot of the Mitre railway, and had a girlfriend named Micaela, whom he stopped seeing because “they won’t let her into Bouwer (prison).” “Did you have any illnesses?” the presiding judge asked. “Yes, schizophrenic,” the defendant replied, mentioning several medications he had to take “since childhood.” “Do you use alcohol or drugs?” “Yes, I used to.” “Before what do you mean?” “Before I was imprisoned.” “Could you take drugs or alcohol while on medication?” “No, because I’d lose it. Why would I lie to you if I’m telling you the truth?” “Do you have any other criminal cases?” “What would that be?” “Records for crimes.” “I’ve been arrested a few times,” Casiva admitted, but the court clerk noted that he “has no relevant criminal record.”“Fabian, what did you do!”

The first witness in the trial was Mónica Beatriz Galíndez, the defendant's mother, who, as such, could have abstained but agreed to answer a lengthy cross-examination by the judges and the parties. The woman recounted that "until he was eight years old, he was like any other child," but in fourth grade, the principal and teachers frequently called her because Fabián "talked back, hit, disobeyed, didn't play like the other children, was always fighting, and would leave the classroom," although "when he was well, he liked going to school." She took him to a psychologist because he also had "headaches and sweated profusely on his forehead." He was then diagnosed with schizophrenia and received outpatient treatment, sometimes inpatient. "Did you ever report your son?" the judge asked. "Yes, I reported him because I put up with everything, but there came a point when we had to report him because we couldn't control him and he needed help," Galíndez admitted, adding that "he tried to commit suicide several times." Despite the schizophrenia diagnosis, the professionals treating him told him that “in some ways he was going to be normal, and he could have one of those episodes every month or every two weeks.” When Prosecutor Arocena asked her how she found out about Azul Montoro's death, the defendant's mother replied, “I didn't know anything.” “It seems you don't want to tell us… What were you doing?” “I was doing housework. He was watching television and I…” “Did you speak with him? How was he?” the official insisted, but before the woman could answer, he turned to the defendant. “I don't know why you're looking at me like that.” “Do you know why I'm looking at you like that? Because you're pressuring my mother,” Casiva retorted, to the astonishment of the judges, jury, and public. “It's fine that you're a lawyer, but you shouldn't pressure my mother.” “That's fine, son, it doesn't bother me,” Galíndez interjected.“He looked at me as if he didn’t know.”

After the judge urged the accused to remain calm, the woman recounted that a neighbor had told her that morning that her son had “killed a trans person.” “Fabián, what have you done!” she demanded. “I don’t know, Mom, I’m upset,” Casiva replied. “How can you not know!” she retorted, adding that she had grabbed his arm and sent him to the provincial Neuropsychiatric Hospital. “Since he was undergoing outpatient treatment, it occurred to me to send him to the Neuro,” the woman explained, clarifying that she went by taxi and asserting that she didn’t see any bloodstains on the clothes her son had asked her to wash. “He looked at me like he didn’t know,” she recalled. Galíndez’s testimony was difficult, filled with conflicting emotions, and will surely play a significant role in what appears to be the central debate of this trial: whether or not the accused is criminally responsible.“We are exposed to vulnerability”

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.