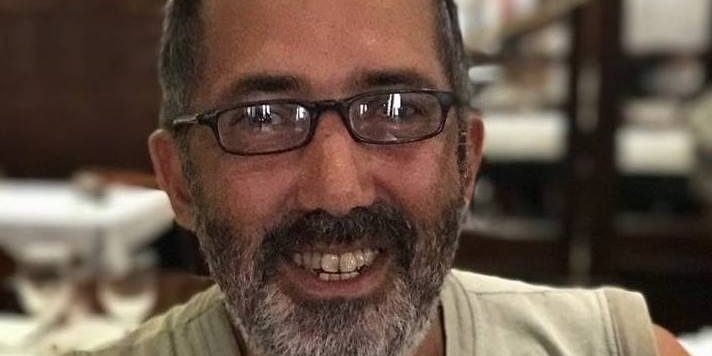

Pablo Pérez on living with HIV: "Saying I'm positive saved me"

Pablo Pérez is a writer who has lived with HIV since the 1990s. In his work, writing and the virus merge to narrate and raise awareness. De Parado Publishing House decided to compile several of the texts Pérez published every Friday in the SOY supplement of Página/12 into the book POSITIVO, chronicles with HIV. These texts, written between 2010 and 2013, are now brought together in this viral, pornographically sensitive journey, written with fluids and ink.

Share

By Lucas Fauno Gutiérrez

Pablo Pérez recounted his life with HIV in the book "A Year Without Love" (1998). He also contributed to the screenplay for the film adaptation. Later, between 2010 and 2013, he wrote columns for Página/12 under the title "I Am Positive," which became a continuation of his earlier work, but with a more collective tone, blending fiction, doubts, debates, and the day-to-day realities of living with the virus.

“I started receiving emails from readers who would tell me their own anecdotes, those of friends, or ask for advice. Later, in my column, I would recount some of them raw, others I would fictionalize, because I also really like serialized fiction, that format that ends with a 'to be continued…', like a written soap opera,” Pérez tells Presentes. It’s Tuesday, and in a little while, the writer, born in 1966, will be giving his writing workshops.

[READ ALSO: “HIV pride is about never giving up the fight”]

Through these 87 columns that make up the book, the author's personal chronicles are interwoven with the stories of characters like L and his relationship with La Masa and La Loba, the problems of the couple formed by P and T. Issues appear such as the hope of a new medication, "you know how every now and then the vaccine 'The Cure' appears or a discussion about X topic, so all this was alternating, it was a playful thing," he says.

One night's sadomasochistic sessions and the next morning's hospital bureaucracy; describing how to suck a cock or how to get it inside without much fuss; relationships with BDSM masters and with doctors—with their differences and similarities—sex and pleasure tinged with fear and uncertainty. From the moment when HIV was a death sentence to the chronic condition of living with the virus, Pablo Pérez writes as he lives. He lives and he writes.

[READ ALSO: #BichoYYo and World AIDS Day: activism isn't just once a year]

In his first book, A Year Without Love , the protagonist, named Pablo Pérez, once diagnosed, assumed that he would die on December 31, 1996. “It wasn’t so obvious that I was going to die before the end of the year, but it served as a literary trick to say whatever I felt like,” he says.

During the writing of this first text, triple therapy appeared, one of the medications that most helped in the treatment of the virus. "' A Year Without Love' could have been an act of exhibitionism without literary value, but for me, as long as it had anthropological value, that was enough," and the result was well-received, as were the columns in SOY positivo, which became part of the history of the virus.

WriteVIHr

Pablo began writing while playing the Ouija board. His aunt had a fit and claimed to be Queen Nefertiti. Eternally young, she worked in bookstores, and in her library, Pablo became a Neruda fanatic. “With the Ouija board, we pretended that Neruda was communicating with us and sending us poems, but I was the one writing them. They were my poems, not Neruda's, and they were bad,” the other Pablo recounts.

The more than five years she spent in writing workshops with Susana Silvestre came to an end when she shared her first BDSM story, and her classmates didn't take it well at all: “We were coming out of the military dictatorship, we were in a democracy, but there was the whole issue of torture, so my story was very poorly received.” Pérez recounted a hookup that ended in a role-playing game with some slapping, a real-life story that later became a text. That's how Pérez writes.

Positive, chronic with HIV

“I liked the edition without dates, as if they were all short stories of the same length, a decision made by Mariano Blatt and Francisco Visconti of Editorial De Parado,” says the writer about this first time that the texts originally born in Página/12 have been compiled.

Having unprotected sex is an obsession for the couple P and T. Between chronicle and chapter, we follow this story with its twists, dialogues, other STIs, and dating websites, and we understand that all these terms and concepts about HIV are narrated here not with statistics but from the perspective of bodies and identities. In July 2018, the World Health Organization (WHO) confirmed that a person on antiretroviral treatment who achieves an undetectable viral load cannot transmit the virus. “This was already being said in doctors' offices,” says Pablo Pérez and his characters, who have been writing since 2010.

“Prevention is always necessary for me. I tried not to take sides, but I'm pro-condoms except in specific cases, in a relationship with complete trust, or when you don't care. The issue isn't so much HIV, but also all the other sexually transmitted diseases,” says the writer, who recounts his entire experience with hepatitis and both protected and unprotected sex in the book.

I am positive in 2018

While Pablo Pérez is writing about POSITIVO, President Mauricio Macri downgrades the Ministry of Health to a Secretariat, the director of the former ministry's AIDS unit resigns due to budget cuts that jeopardize the continuity of treatments, and Dr. Albino claims that condoms are ineffective. It's 2018, and Pérez reflects: “What's happening is a catastrophe. My idea in writing SOY Positivo was to keep the issue in the media; simply mentioning it already says, 'This exists, it's not over, there are new debates, it exists.' So, even if the book is poorly written, even if some things are nonsense, it's still important to raise awareness of the issue.”

In addition to the 87 columns selected by De Parado, two texts are included: “Chronicle of a Foretold Cut” from 2018 and a 2010 report in which Pérez speaks with his infectious disease specialist. From beginning to end, from 2010 to 2018, these two texts are interwoven with the 87 columns. They read with almost the same timelessness as the entire book, since, unfortunately, many of the problems and complaints at the beginning and end remain relevant, recurring and resurfacing.

“It’s funny, because when we refer to our HIV-positive status, we say ‘I’m positive,’ and, in my opinion, after twenty years of living with the virus, I can say that this is the attitude that saved me,” Pérez narrates in his first column and on the back cover. He opens and closes with a positive attitude.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.