Gender is being rewritten: Is the future non-binary?

A journey from Simone de Beauvoir's feminism through queer theory to reclaimed rights. Is the future non-binary?

Share

The fight against heteronormativity has brought non-hegemonic identities into the spotlight, challenging biological paradigms and driving a cultural and legal shift that has already been enshrined in law in Argentina. Nevertheless, conservative groups like "Don't Mess With My Children" criticize feminism and LGBTI+ activism by referring to it as "gender ideology." As an introduction, to understand how the notion of gender is being rewritten daily, we'll explore its evolution from Simone de Beauvoir's feminism through queer theory to the rights that have been reclaimed. Is the future non-binary?

Two days after March 8th, journalist Jorge Lanata published a column in the newspaper Clarín, supposedly in favor of equality between men and women, but where, in reality, he railed against feminism or, as he calls it—following American critics—"gender feminism" or "radical feminism." For Lanata, current feminist demands are victimizing and hinder women's fight for equality.

According to him, there is no such thing as a patriarchal system. Furthermore, Lanata continued, this "bad" feminism ignores biology. To support his claims against "radical feminism," he cited an experiment by a woman named Melisa Himer with toys and infants . The study demonstrated that, given the choice, baby boys preferred trucks and baby girls preferred dolls, thus settling the debate about biological determinism and gender.

First: Melisa Himer doesn't exist. Whoever wrote the article for Lanata must have gotten that information from a 2006 article in El País of Spain , which already contained that error, and which was later replicated as fact on several websites. Second: a Melissa Hines does exist, and she conducted a similar experiment. Third: she did the experiment with primates, and the results are highly dubious.

The notion of gender as a social construct and its separation from sex is nothing new, and identities that don't fit into fixed categories are even less so. So, neither fads nor revolutions (as National Geographic its January 2017 issue) nor ideologies. What does exist is greater media visibility worldwide—stemming from feminist demands and LGBTI activism—accompanied by a slight improvement in terms of rights, depending on the region, and above all, by a conservative social reaction, known as "backlash," which manifests itself both in the constant transphobic statements of local figures like Lanata or Agustín Laje, and in global anti-rights movements like "Don't Mess With My Kids" (funded by evangelical churches), which oppose sex education manuals and are gaining significant traction in Latin American societies and parliaments.

In Argentina, the most recent example is that of the legislators who first opposed legal abortion and then the reform of the Comprehensive Sexual Health Law, and the lobbying power of the "celestial party", the self-proclaimed "pro-life".

From “one is not born a woman” to “one is not a woman”

In 1949, the French existentialist philosopher Simone de Beauvoir published *The Second Sex *, a nearly 1,000-page essay analyzing the various roles of women from historical, anthropological, psychological, and political perspectives. It was during this research—and based on its findings—that Beauvoir became a feminist. Her work was the most comprehensive study of "the feminine" up to that time and marked a turning point in the women's movement.

Michel Foucault's studies on sexuality and power, the essays of the French lesbian feminist author Monique Wittig, and LGBTQ+ activism challenged feminist theories, since (as the Italian theorist Teresa de Lauretis pointed out) they always presume heterosexuality. From the 1980s onward, what is known as "queer theory," a branch of gender studies focused on LGBTQ+ identities, burst onto the academic scene and into discussions about feminism.

American philosopher Judith Butler brought about a Copernican shift in thought with her book Gender Trouble (1990). In it, she argues that gender is not constructed from the sexual binary, but rather that the very idea of "sex" as something natural was interpreted through the lens of gender binarism. Therefore, for Butler, gender is no longer the expression of an inner being but a repeated and obligatory performance based on norms that transcend us. And this performance is, ultimately, a negotiation with those norms. She calls this "gender performativity."

American philosopher Judith Butler brought about a Copernican shift in thought with her book Gender Trouble (1990). In it, she argues that gender is not constructed from the sexual binary, but rather that the very idea of "sex" as something natural was interpreted through the lens of gender binarism. Therefore, for Butler, gender is no longer the expression of an inner being but a repeated and obligatory performance based on norms that transcend us. And this performance is, ultimately, a negotiation with those norms. She calls this "gender performativity."

In this region of the world these ideas were also discussed and integrated, and local reflections were added, such as Latin American transvestite theory, with exponents like Lohana Berkins or Marlene Wayar.

[READ ALSO: #BOOKS Marlene Wayar: South American transvestite-trans theory]

To speak of gender, from a queer theory perspective, is to speak of power relations, and not embodying the binary norm means not being seen as a complete subject and even risking one's life. This happens to trans people, non-binary people, masculine lesbians, and all identities that historically have not fit into the "stability of gender": an alignment between sex, gender, and sexuality.

Therefore, following Butler, there is no such thing as “being a woman” or “women” or “being a man,” but rather a performativity. And this performativity allows gender norms to be open to reinterpretation and social transformation.

From gender dysphoria to the gender identity law

Theoretical discussions, conceptual explorations, and the struggles of feminist and LGBTQ+ activism have created greater spaces of freedom for diverse gender expressions. However, political, legal, and medical powers have not kept pace with these demands, often lagging behind and unsure of how to respond, and generally offering resistance.

The term “gender dysphoria” was first used in the field of American psychiatry in the 1970s. Trans people—or anyone who did not conform to the gender they were assigned at birth—were considered to be suffering from a mental disorder. This pathologization of non-binary, non-cisgender identities had—and continues to have—a correlation at the police and judicial levels. By considering them ill, people with identities that do not fit into a heterosexual and cisgender norm are excluded from social spheres—from education to the workplace—and are frequently criminalized by law enforcement.

[READ ALSO: For the WHO, being trans is no longer a mental illness]

Despite the increased visibility of trans identities in the media and popular culture, as well as greater access to rights in some countries, until this year the World Health Organization (WHO) continued to classify trans people as having mental illnesses. In June, the ICD-11, a manual for identifying global health trends and statistics that had not been updated since 1990, incorporated a long-standing demand from LGBTI communities by creating a new chapter on “Conditions related to sexual health.” It is now called “gender incongruence”—a term that remains controversial—and is classified as a “condition related to sexual health.”

The WHO describes it as “a profound aversion or discomfort with one’s primary or secondary sex characteristics,” a “strong desire to be free of” some of these characteristics, and a “strong desire to have the primary or secondary sex characteristics of the experienced sex.” This change comes late for some countries, such as Argentina, which already has a gender identity law and is one of the states where transgender people have the legal right to change their gender identity and name on their documents.

But this decision by the WHO is a crucial step forward : many countries still need this type of global ruling that clearly states that "trans people are not sick" in order to pass laws that protect them and guarantee their rights.

[READ ALSO: What we talk about when we talk about “cis”]

Since May 2012, Argentina has had a progressive Gender Identity Law (Law 26.743), one of the best in the world: in addition to recognizing the right to self-perceived gender identity, it includes comprehensive healthcare—with genital reassignment surgery and hormone therapy—and provides—in theory—greater legal protection. In other countries with such laws—Uruguay, for example, which has had one since 2009—it only allows for the possibility of changing one's name on identity documents.

Chile took a historic step: after five years of back and forth, on September 12, the Chamber of Deputies approved the Gender Identity Law, with 95 votes in favor and 46 against. While the vote was taking place inside the Congress building in Valparaíso, outside, evangelical groups chanted slogans against the advancement of rights.

Violence motivated by prejudice and a landmark ruling

While achieving legal recognition is a tremendous accomplishment, the struggle for transgender people doesn't end with an identity document. In Latin America, according to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights' (IACHR) report on violence against LGBTI people, the life expectancy of a transgender person is 35 years. Furthermore, an average of nine LGBTI people are murdered every week in the region due to hatred based on their sexual orientation or gender identity, and the majority of these victims are transgender, who are also a primary target of institutional violence.

The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) refers to violence against LGBTI people as “bias-motivated violence” because it is perpetrated against “people perceived as transgressing traditional gender norms, the male/female binary, and whose bodies differ from standard ‘female’ and ‘male’ bodies.” These are crimes linked to prejudice or negative reactions to non-heteronormative expressions. Bias-motivated violence does not operate in isolation, but rather within a framework of social complicity and a specific context (an educational, cultural, or religious framework). Those who perpetrate it seek to “punish” these identities and otherness with high levels of cruelty and savagery.

[READ ALSO: #DianaSacayán: This is how the first day of the trial for transvesticide was experienced]

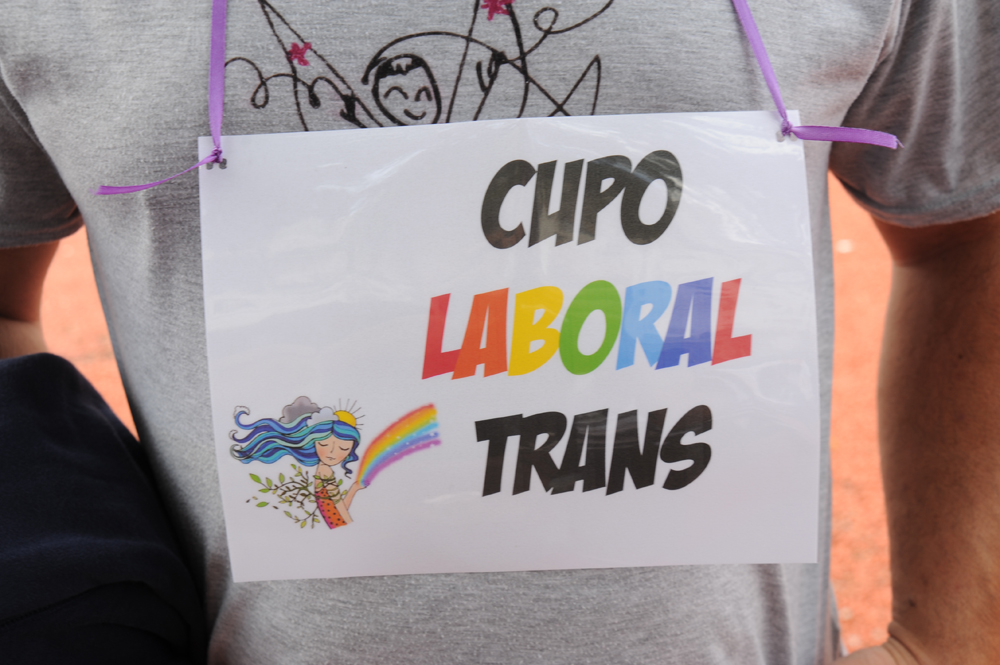

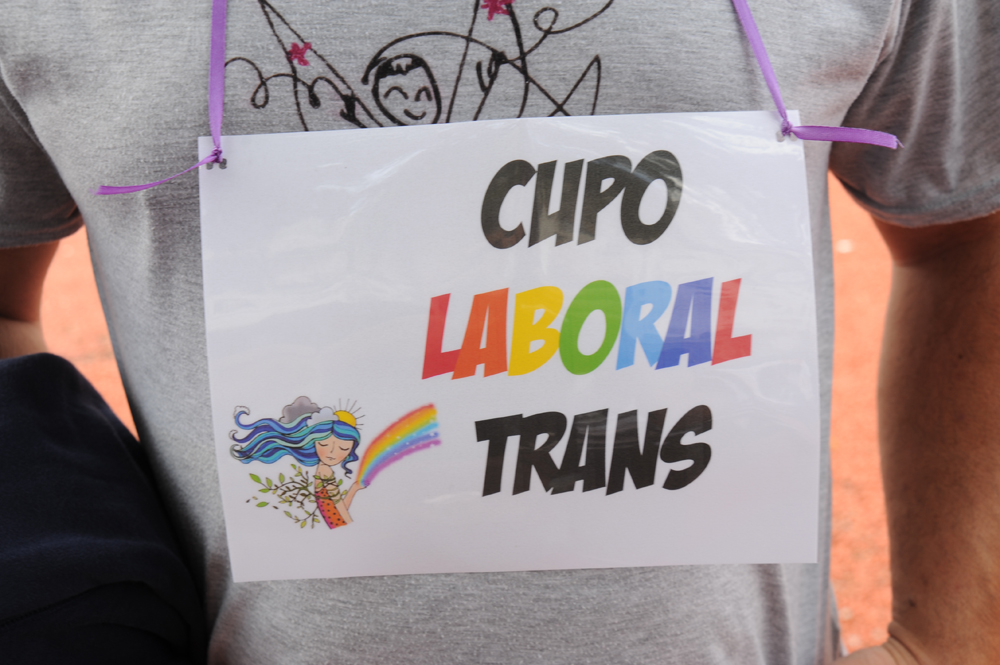

On the same day that the WHO removed transsexuality from its list of diseases, the Argentine justice system issued a landmark ruling. It was in the trial for the murder of Diana Sacayán, the trans activist and human rights defender, creator of the trans employment quota (now a national bill), driving force behind the Gender Identity Law and numerous other emancipatory initiatives, who was murdered in October 2015 in her own bedroom, in the apartment in the Flores neighborhood of Buenos Aires where she lived.

Court No. 4 sentenced Gabriel David Marino to life imprisonment as an accomplice in the crime of aggravated homicide motivated by hatred of gender identity and by the presence of gender-based violence. It was the first time in Argentine history that the justice system heard the voices of transvestite and transgender people, not as victims of fabricated cases by the police, but to recount the multifaceted structural violence they experience and against which Diana fought.

In the midst of the trial, at the request of the family's legal team, headed by lawyer Luciana Sánchez and led by Diana's brother, Say Sacayán, anthropologist and muxe activist (a term referring to an ancient gender identity) Amaranta Gómez Regalado traveled from the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, Mexico, to give a master class as an expert witness. In the courtroom, Amaranta spoke about gender identity, politics, culture, and violence. She discussed cisgender as a hegemonic category and gender binarism, and the schizophrenic nature of Spanish, where there seems to be no third gender or space, unlike in the Zapotec language, which has articles that refer neither to masculine nor feminine. “We must assume that there is a third space, without confining it,” Amaranta said, and recalled that in Mexico, Canada, Panama, Polynesia, Fiji and India, and in the Navajo culture of the United States, there were trans and/or non-hegemonic identities linked to indigenous cosmogonies, pre-existing the colonial process.

[READ ALSO: The muxes, a millennia-old transgender identity]

The ruling states verbatim, several times, “transvesticide,” “structural violence,” and “patriarchy.” It cites definitions from Judith Butler, Michel Foucault, and Rita Segato. It speaks of the body as a social, cultural, and political entity, where patriarchal society deposits stereotypes and exercises naturalized power relations, because it is in the body, the ruling states, that the asymmetry of power in relationships is reproduced.

Is the future non-binary?

Despite the progress in the visibility of non-hegemonic identities – which cover a very broad range, from the judicial sphere to the daily use of inclusive language, strongly embraced by new generations – the fight against heteronormativity is played out minute by minute in a more stark and violent way than some media outlets portray.

In that issue of National Geographic , titled “The Gender Revolution,” the subscriber edition featured a trans girl on the cover. Non-binary children are gaining more prominence, and activists say that this is where the future of the struggle lies. But the integration of these identities is far from a reality, both in popular culture and in educational and healthcare settings, where diverse bodies are not considered.

Gabriela Mansilla, Luana's mother—Luana being the first trans girl in Argentina to obtain her national identity document after the Gender Identity Law was passed—and founder of the organization Childhoods Free of Violence and Discrimination, offers some insights into how to move forward. “The struggle against the binary and stereotypes is constant, every day, in every space. It is urgent to enable, integrate, accept, name, teach, and explain dissident bodies. We must listen to the child. We must look them in the eyes and ask: What do you need? What are you feeling? What's happening to you? Don't you like pants? Do you want a skirt? What would you like me to call you? What would you like to play?”

*This article was also published in the T magazine of Tiempo Argentino

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.