The LGBTI movement in Chile after Pinochet

In 1988, without being on the immediate agenda of the democratic parties and in the midst of a complex context of political negotiations between democratic civilians and coup-plotting military officers, the demands of the LGBTI movement emerged.

Share

By Víctor Hugo Robles

Photo: Iris Colil

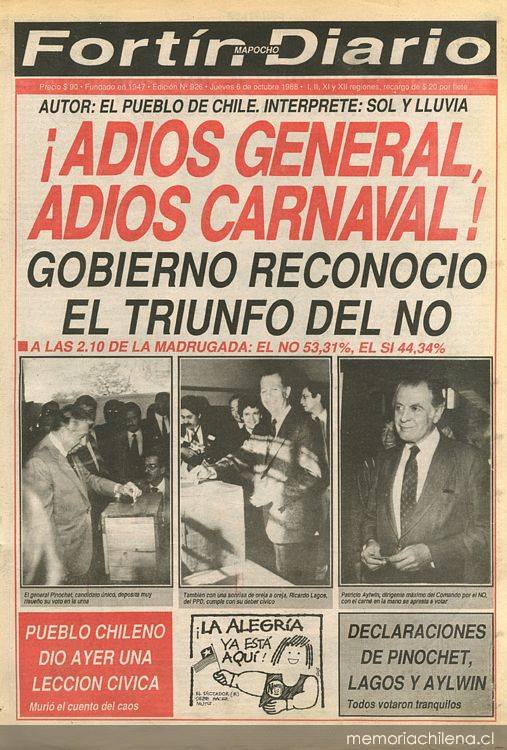

Following Augusto Pinochet's defeat at the polls on October 5, 1988, new political horizons emerged for the Chilean gay, lesbian, and trans movement. During this period of democratic transition, a militant, active, and public voice was articulated. While not on the immediate agenda of democratic parties and amidst a complex context of political negotiations between democratic civilians and the coup-plotting military, the demands of the LGBTI movement burst onto the scene.

Its symbolic importance was expressed in the introduction of the gay issue into the national public debate. The transition to democracy in Chile represented a process that not only allowed for free elections that brought Patricio Aylwin to the presidency, but also fostered the emergence of utopian ideals of social transformation, such as the liberation of homosexuality in Chile. The newspaper La Tercera, in an extensive investigative report published on June 11, 1993, described the Chilean gay rights group as "signs of openness" in Chile.

A diagnosis

A workshop on civil rights held on June 28, 1991, at the Chilean AIDS Prevention Corporation, the precursor to the historical Movilh (Movement for Homosexual Integration and Liberation), served as the basis for an initial assessment of the discrimination faced by gay, lesbian, and transgender people in Chile. After heated ideological debates, the gay and lesbian participants at the workshop agreed on the main problems they faced, including social rejection, repressive sex education, violations of individual freedom, employment difficulties, and limited access to healthcare for people living with HIV/AIDS.

The diagnosis also established the founding objectives of the movement: “To organize homosexuals, to educate and raise awareness about their reality, to create a political strategy to access the means of power, to promote change, to foster freedom of expression and to have a physical place to work.”

The group's founders shared a broad consensus regarding the discrimination they faced. However, this did not preclude ideological differences within a diverse group. From the outset, members came from various backgrounds: students, employees, artists, laborers, and professionals. The majority were gay men, with the exception of Iris Colil, a photographer who supported the activities of the nascent gay rights movement. While most had participated in the struggle against Pinochet's civic-military dictatorship, there were also those who expressed little or no interest in political matters.

March for Human Rights

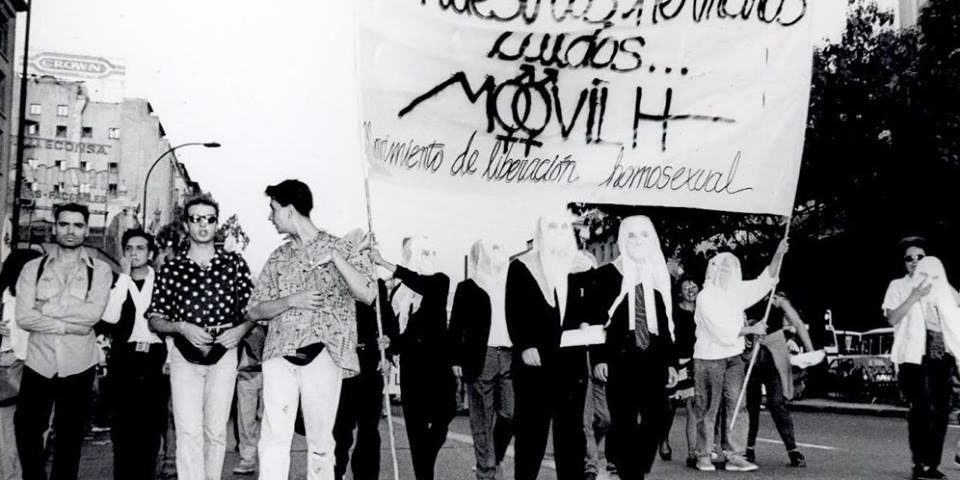

On March 4, 1992, human rights organizations called for a march to commemorate the official delivery of the Rettig Report, a document prepared by a special commission appointed by President Aylwin, whose name was due to Raúl Rettig, the deceased lawyer, president of that commission.

The organization's objective was to investigate human rights violations perpetrated during the military dictatorship. According to journalist Alejandra Matus in her publication, The Black Book of Chilean Justice : “ The Rettig Report recognized for the first time the responsibility of state agents in human rights violations, provoking a sharp conflict between the Executive, Judicial, and Armed Forces branches of government.”

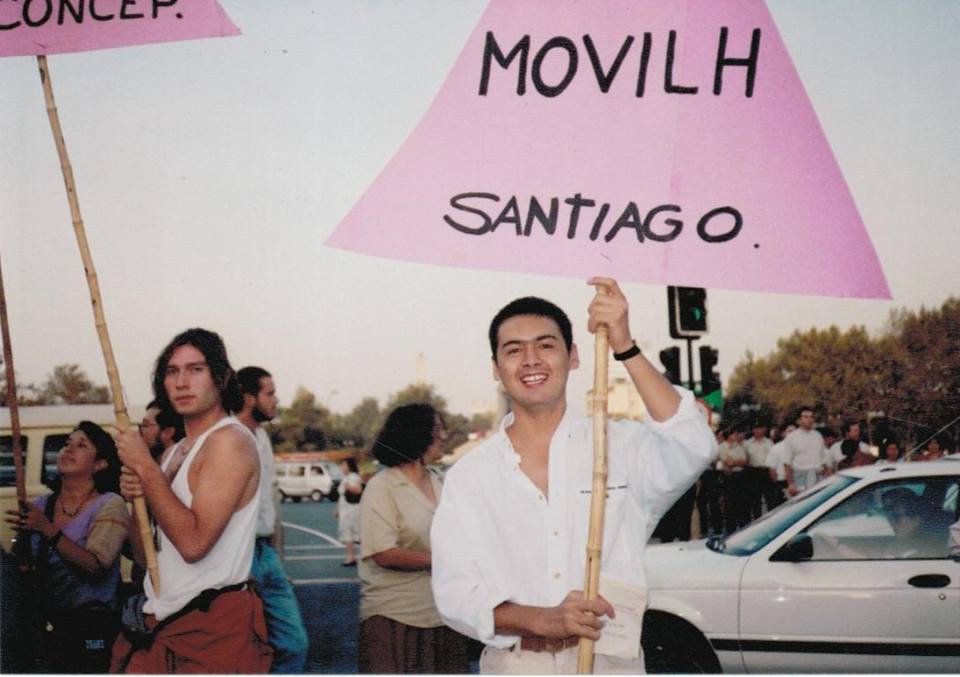

The Historical Movement of Homosexual Integration and Liberation (Movilh Histórico) saw this as a historic opportunity to join other social struggles, agreed to take to the streets, and participated in the rally. On that occasion, around ten masked homosexuals appeared, dressed in mourning and carrying a banner that read: “FOR OUR FALLEN BROTHERS. HOMOSEXUAL LIBERATION MOVEMENT.” Although they positioned themselves at the back of the march, on the left, the reactions were immediate. Most expressed astonishment, while women voiced their sympathy, and others wished to march far away from the homosexuals.

Juan Pablo Sutherland, writer and leader of MOVILH (Movement for Homosexual Integration and Liberation), explained the reasons for the gay presence in the march in an interview with the now-defunct magazine El Canelo: “ We participated because we felt the need to speak out as a social movement regarding an issue directly linked to the reality of homosexuality: respect for the dignity and rights of the human person.”

The symbolic importance of being at the back of the march, as a kind of final stand, coupled with the fact that it arose during a period of political negotiations between civilians and the military, reinforced the sense of astonishment that the defense of a sanctioned sexuality produced in the public sphere. As Jorge Pantoja, psychologist for MOVILH Histórico, stated during the first seminar on sexuality and homosexuality, held at the University of Santiago, Chile, in October 1994: “ Through the participation of homosexuals in this historic march, the movement was able to channel demands born in the private sphere into a public political space, a space that was booming due to the return to democracy.”

*Excerpt from “Hollow Flag: History of the Homosexual Movement in Chile” by Víctor Hugo Robles

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.