Gay, Mapuche, and feminist: a young Chilean man questions through art

Sebastián Calfuqueo's work speaks to history, to society, and to those who have denied their identities: "In their lands and in their culture, we Mapuche faggots wallow. Those that nobody wants," says this 25-year-old.

Share

Sebastián Calfuqueo's work speaks to history, to society, and to those who have denied his identity: “In their lands and in their culture, we Mapuche faggots wallow. Those that nobody wants,” says this 25-year-old. By Lucas Gutiérrez

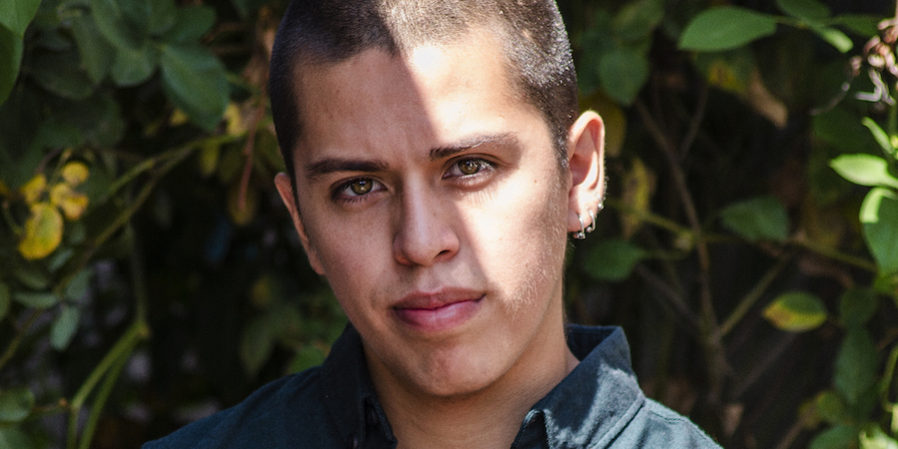

Photos: Diego Argote and Cristian Gómez. Sebastián Calfuqueo is 25 years old and lives with the intersection of several identities: Chilean, Mapuche, gay, and feminist. From a very young age, he suffered violence and discrimination, and over time, he has exorcised it through art. Calfuqueo is a visual artist. His work addresses the intersections of Mapuche identity with class and gender. He does so through irony and denunciation, appropriating objects, installations, and audiovisual resources to transcend imposed boundaries. His work speaks to history, to society, and to those who have denied his identity: “In their lands and in their culture, we Mapuche faggots wallow. Those whom nobody wants,” he tells Presentes .

Searching for roots

During his early teens, the urban Sebastián who frequented pre-Facebook social media and began searching for his identity within urban tribes started to question his place, his identity. “Having gone through all these urban tribes, I understood that I also had to take responsibility for a history I carried socially and culturally, a history that had been denied to me,” he says. But his grandmother’s words kept echoing in his head: “There are no faggots in the Mapuche community.” There was something about homosexuality that didn’t seem to connect with Mapuche culture at any point. Until he learned the story of the Weyes.You'll never be Weye

It is Calfuqueo's voice that utters this phrase during the video performance 'You will never be a Weye'. Before the arrival of the Spanish in the lands we now call Chile, there were the Weyes. These individuals did not conform to the gender binary, moving between masculine and feminine. The conquistadors wrote in their diaries about the Weyes: "This one looked like Lucifer in his features," and they exterminated them, alleging sodomy. 'You will never be a Weye' seeks to demonstrate the union between queerness and Mapuche culture: "These were two things that historically could not be combined. According to official history, there was this discourse that homosexuality is a construct of the contemporary West, almost a bourgeois vice, and not something that previously belonged to our original tribe."

Deflated pride

Eighteen ceramic pieces shaped like rubber ponies in the colors of the pride flag: deflated at first, filled with content at the end. This installation by Calfuqueo is called 'Not So Pride' (2014) and directly addresses the internal dynamics of the LGBT movement. “Here in Santiago, when the Pride March takes place, at the beginning come the more mainstream groups like MOVOLH or Fundación Iguales, groups representing a very sanitized, normalized gay man. This gay man doesn't talk about politics, gender identity law, or abortion; all he wants is to get married. And at the end come the sexual dissidence groups,” Calfuqueo points out.

Mapuche feminism

Within his solo exhibition titled “Contested Zones,” the artist presented a video in which five Mapuche and feminist women deconstruct the colonial image that weighs on Mapuche femininity. The work is called “Domo,” which in the Mapuche language, Mapudungun, means “woman.” One of them, Doris Quiñimil, studies lawen, a medicinal herb. Through autonomous and ancestral knowledge, she shares how abortion can be performed using it, as women have historically done. Doris Quiñimil also introduces a term: hetero wingka patriarchy. Wingka It's a Mapuche term that refers to a foreigner. So, to speak of hetero wingka patriarchy It's about understanding that heteropatriarchy also operates under colonial conditions. “For example, an Indigenous woman suffers much more severe violence than a white woman. We are permeated colonially by the wingka“And hetero,” says Calfuqueo about this concept. wingka"Because heteronomy is the norm," she concludes.“Break the hetero-wingka patriarchy ”

Calfuqueo is currently part of 'Rangiñtulewfü Kolectivo Mapuche Feminista'. “We are Mapuche, we are champurrias “(Mestizo), we are feminists and we are fighting,” is the group’s motto. And although it was recently created, he says they are trying to generate a new space for being Mapuche. While he has received solidarity from colleagues who have experienced what he reflects in his work, he hasn’t yet received much of a response from the Mapuche community. “These are difficult spaces to access when you come from the capital. I wasn’t raised within a community from a young age; I was formed in the Mapuche identity "Much later, because the city also colonizes the subjects too much," Calfuqueo explains.“Art allows us to create a rupture.”

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.