When Chilean transvestites took to the streets for the first time

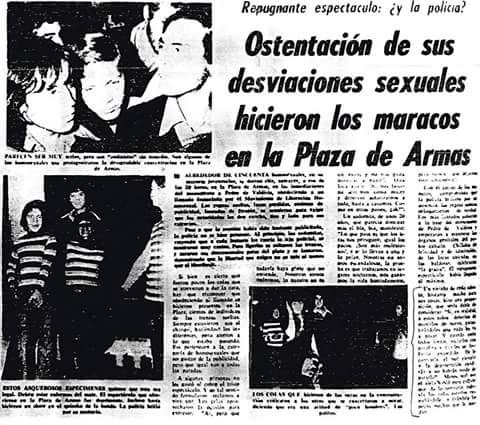

In April 1973, a group of young transvestites took to the streets, marking the beginning of the intense struggles for diversity in Chile. This was met with total rejection from the press in a politically turbulent climate. “Faggots flaunted their sexual deviance in the Plaza de Armas,” headlined the newspaper Clarín.

Share

On Sunday, April 22, 1973, a group of young transvestites took to the streets, marking the beginning of the intense struggles for diversity in Chile. This was met with total rejection from the press in a politically turbulent climate. “The faggots flaunted their sexual deviance in the Plaza de Armas,” headlined the Chilean newspaper Clarín.

By Víctor Hugo Robles

On Sunday, April 22, 1973, the first LGBTQ+ protest in Chilean history took place. It was a time when the protagonists of this historic event— Raquel, Eva, Larguero, Romané, José Caballo, Vanesa, Fresia Soto, Confort, Natacha, Peggy Cordero, and Gitana —would meet to talk in Santiago's Plaza de Armas, seeking to improve their chaotic, working-class lives and imagining a desired yet uncertain future.

The shocking act, carried out by a group of young transvestite prostitutes, marked the beginning of the intense struggles for diversity in Chile and was met with total condemnation from the press during a turbulent period. “Faggots flaunted their sexual deviance in the Plaza de Armas,” headlined Clarín, the most widely circulated and popular newspaper, which championed the political, social, and cultural transformations desired by the late socialist president Salvador Allende.

The controversial and unprecedented public demonstration took place on the same day that the far-right group "Fatherland and Liberty" detonated a bomb at the Che Guevara monument in the San Miguel district of Santiago. While the political world focused its attention on the terrorist attack during a time of social unrest leading up to the September 11 coup, the sensationalist press ran wild covering the details of a public demonstration unlike anything ever seen in our homophobic society, a demonstration whose protagonists were a group of homosexuals who had little or nothing to lose, and everything to gain.

"At that time, nobody defended us."

“ La Raquel,” one of the protagonists of the event, recalls in the book “Bandera Hueca. Historia del Movimiento Homosexual de Chile” (Hollow Flag: History of the Homosexual Movement in Chile): “We protested because we were tired of the discrimination. In those years, if you were walking down the street and the cops realized you were gay, they would arrest you, beat you, and cut your hair just for being gay. The jails and police stations were like hotels for us. At that time, nobody defended us; we didn't even have the support of our families because we ran away from home as young girls to live more freely.”

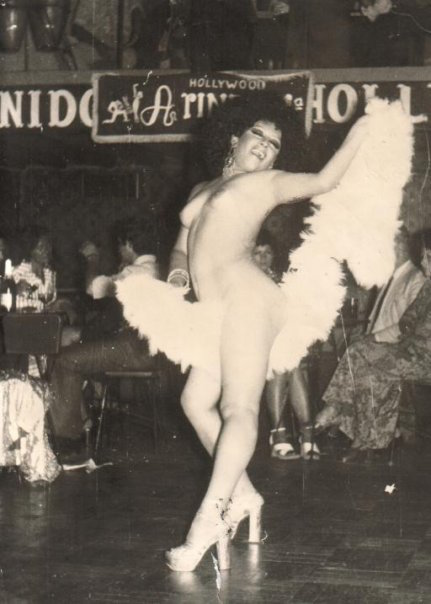

Until that moment in Santiago's Plaza de Armas, the "maracos," "loose mares," "lost queens," "faggots," "queers," "queers," "faggots"—as the press of yesteryear called homosexuals—did not appear organized or emancipated anywhere. They only appeared in reports about the first sex reassignment surgery that legally transformed Marcia Alejandra Torres into a woman, in cases of sodomy, or in police raids against the transvestites who danced and engaged in sex work at 1226 Vivaceta Street in the capital, the location of the legendary brothel of Chile's most famous queen of prostitution, Carlina Morales Padilla, "Aunt Carlina."

During the Popular Unity government, homosexuals were seen as human scum; their demands were nonexistent, not even considered in the political, social, and cultural changes that President Salvador Allende aspired to implement. “In those times there was more political freedom, but there was no freedom for us. In those years, people were horrified and scandalized by us, even though homosexuality was more hidden, not like now when it's more liberal,” recalls Raquel .

Journalistic homophobia in the 70s

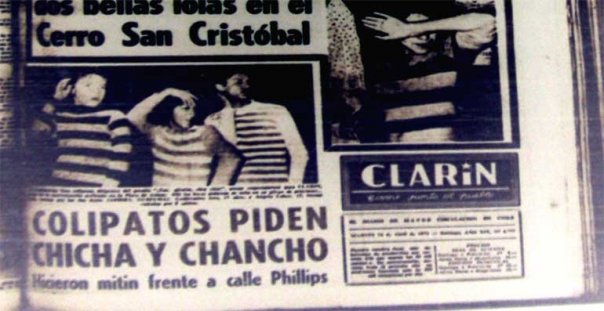

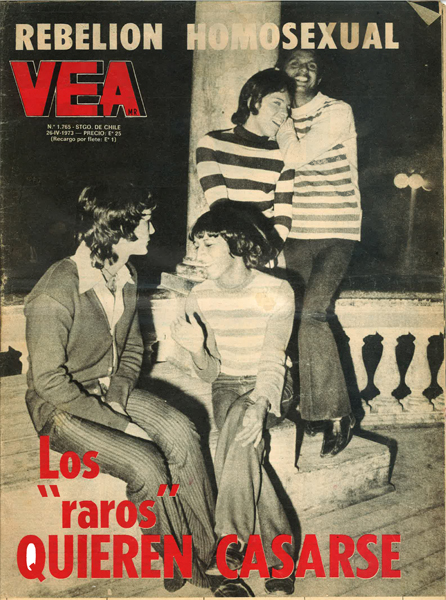

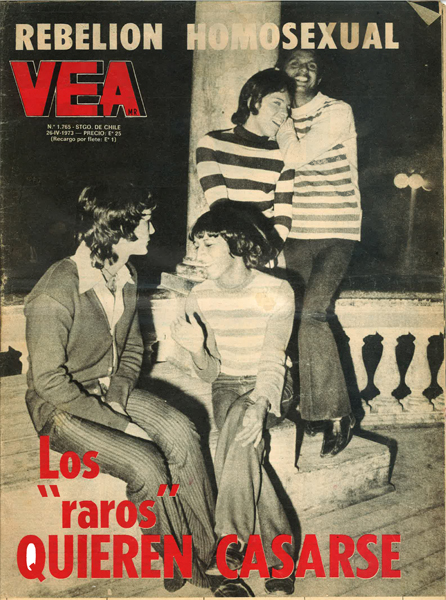

No one escaped the shock, prejudice, and crude commentary, particularly the left-wing press, which went out of its way to attack the first homosexual demonstration. “The freaks want to get married,” headlined the sensationalist magazine VEA on its colorful cover, while the pro-communist magazine Paloma reported on “50 abnormal people gathered in the Plaza de Armas.” For its part, the newspaper Clarín followed suit with the headline: “Faggots demand chicha and pork.” Inside, Clarín wrote: “The loose mares, crazy and desperate for publicity, boldly gathered to demand that the authorities give them free rein for their deviance. Despite the fact that the meeting had been widely publicized, the police were nowhere to be seen.”

In an excessive and alarming manner, and in a clear public moral condemnation of sexual dissidents, Clarín declared: “At first, the sodomites, believing that the police would come down on them at any moment, were cautious. But they quickly let their hair down, took their enormous legs out of the dish, and launched themselves, demonstrating that the freedom they demand is nothing more than debauchery. Among other things, homosexuals want legislation so they can marry and do whatever they want without police persecution. Imagine the uproar! No wonder an old man suggested dousing them with kerosene and throwing a lit match at them.”

Shortly afterward, the growing social unrest that divided the country, the hostile press that portrayed homosexuals as criminals, the threats of a military coup, and the police persecution unleashed after the protest, forced homosexuals to retreat into their sheltered spaces, awaiting better political conditions to resume the struggle. There, in the ostracism of private meetings, parties, and clandestine gatherings, they waited to return to the public arena. However, the wait was long because the military coup of September 11, 1973, arrived with its bitter history of exile, torture, deaths, and forced disappearances.

Homosexuals, lesbians and transvestites tortured and murdered in brothels and poor neighborhoods are to this day the most forgotten victims of the bloody history of the Chilean military dictatorship.

Post-Pinochet Chile

“Remembering La Natacha, La Lucha, La Doctora, La Katty Fountain, La Gitana, La Fresia Soto, and so many others in their political protest interventions, only reminds us that we are still following the lines of social injustice, the same lines of injustice that their colorful vintage vests symbolized, the lines of the disappeared detainees, the lines of prison, the lines of the norm, the lines of oppression that divides, that segregates, and continues to install the same families in power, but now with a variation of sexual orientation and gender,” says Dimarco Carrasco, archivist and historian of the Luis Gauthier Documentation and Memory Center of the Movement for Sexual Diversity MUMS.

“Thinking about the crazy women of '73 – continues Dimarco Carrasco – is thinking about the trace, but not just a trace as traditional historiography describes it, but thinking about a fugitive trace that survived surreptitiously from the policies of erasure of the dictatorship, that is, as a word-of-mouth rumor that knew how to travel through time until it emerged in a local neoliberal scenario where it is updated in its most heterogeneous versions, from a poster in the street to a museum exhibit.”

Marcia Alejandra Torres, the first trans woman reassigned in the history of Chile

For his part, Marco Ruiz, founder of the Historical Movement for Homosexual Liberation (Movilh Histórico) and current member of the Observatory of Public Policies on HIV/AIDS and Human Rights at the Savia Foundation, points out that the changes and progress from the first gay rights protest to present-day Chile cannot be quantified. “I can say that in recent years, groups and organizations have emerged in various spaces, including university settings, where interesting discussions and reflections have taken place from an academic perspective on issues of gender, gender identities, and sexual identities,” he says.

Looking at the struggles of the present from the perspective of the past, Marco Ruiz concludes: “Today we continue to experience violence and death against gay, lesbian, and trans people at the hands of a patriarchal and heteronormative system. Furthermore, LGBTQ+ individuals and organizations have not risen to the occasion in publicly addressing these deplorable events. There is a significant lack of advocacy regarding public policies on HIV/AIDS; the latest data released by health authorities is alarming. Considering the years that have passed since the pandemic took hold in our country, adequate strategies have not emerged from LGBTQ+ groups to provide an integrated response to the epidemic.”

Today's trans women

“In Chile, just as 44 years ago, the date of the first recorded protest on gender and sexual dissent, change has always been the product of the work of social organizations and, primarily, of strong and visible trans, lesbian, and queer people who walk the streets and neighborhoods every day and night,” says Niki Raveau of Fundación Transitar, an emblematic organization that brings together trans families, youth, and children. “Change has only come at the cost of putting our bodies on the line, making ourselves visible, and standing tall. Legal and institutional changes are minimal (for example, the incomplete Anti-Discrimination Law), and it is often the institutions themselves that foster transphobia and the erasure of communities (the deletion of individuals),” she adds.

“In Chile,” Niki Raveau observes, “if you’re not ‘man’ or ‘woman’ according to criteria that no one wrote or agreed upon anywhere, then you have less right to anything.” “And if you live on the street or don’t have a community to support you, your rights are null. You don’t exist. Same-sex marriage, as an official LGBTI victory, stifles and obscures all those other truly urgent struggles. When schools aren’t centers of innovation and thought, they become heterosexual market models, where only those who are well-disguised and have resources get in. Our work must be re-examined; the immutable and unquestionable LGBTI discourses and agendas must be challenged,” concludes the renowned transgender activist.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.