“Your voice persists”: Lemebel as told by his lovers

Two years after the death of the Chilean chronicler, activist and performer, Pedro Lemebel, a Latin American reference point for sexual dissidence and countercultural literature, his friends and colleagues – his loves – construct a collective portrait from his absence, which makes him shine brighter than ever.

Share

Two years after the death of the Chilean chronicler, activist and performer, Pedro Lemebel, a Latin American reference point for sexual dissidence and countercultural literature, his friends and colleagues – his loves – construct a collective portrait from his absence, which makes him shine brighter than ever.

“Your voice, your voice, your voice, your voice exists,” we sang excitedly to the tune of Lucha Reyes, remembering Pedro Lemebel in a tribute on January 19, 2017 at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Santiago, Chile.

“Your voice, your voice, your voice, your sweet voice, your voice persists,” we chanted with collective force, paying tribute to and challenging the presence of the crazy mother of Chile who marked the rough paths of proletarian, rebellious, red, daring and insurrectionary queers, lesbians and transvestites.

His fiery, literary name is part of the Latin American popular imagination, where his urban chronicles are read from community libraries to universities, and his personal life is studied and researched by national and international journalists and biographers.

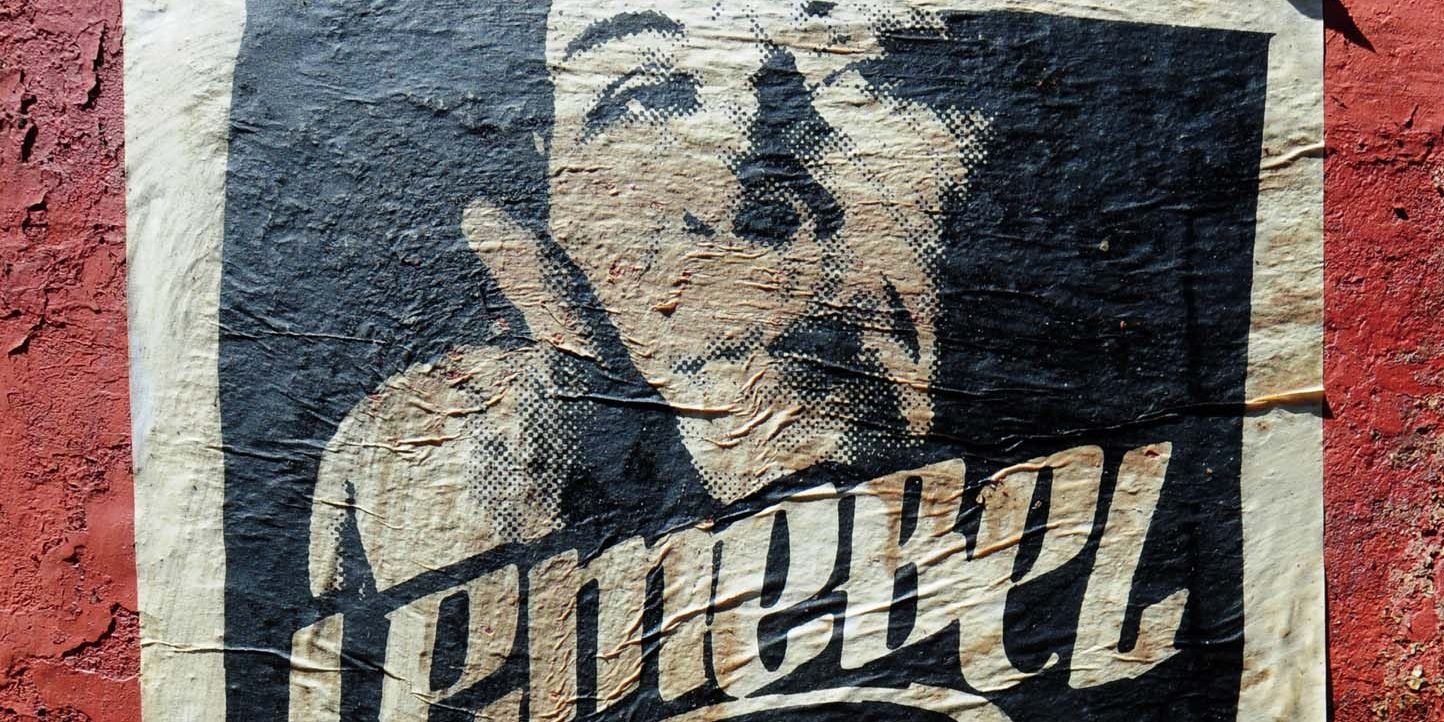

“Lemebel’s voice has spread and become ubiquitous in street graffiti, political collectives, and canons of art and literature. His voice is part of a popular matrix that constitutes Chile in relation to itself and to the world,” observes Marcial Godoy-Anativia, from the Hemispheric Institute of Performance and Politics at New York University.

Today, January 23, 2017, we commemorate two years since the death of Pedro Segundo Mardones Lemebel. His absence is keenly felt, his sharp, necessary, and unsettling voice amidst the institutional accommodation of demands for normalization of local sexual diversity.

What would you think of Chile today?

“I’m not a ring-wearing lunatic,” the rebellious Lemebel would say when asked about same-sex marriage or Chilean-style civil unions. And so, amidst memories, tributes, presences, and absences, Pedro Lemebel appears and reappears in our present time, disguised in multiple formats and expressions: visual exhibitions, TV programs, literary tributes, posthumous books, and even the legislative approval of a monument in his honor in the popular Recoleta district of northern Santiago—a parliamentary initiative promoted by the Communist Party of Chile. I wonder: Would Pedro Lemebel have wanted a monolith in his honor? Surely not, although some value it as a beautiful, just, and necessary gesture.

Today, his fellow travelers, his allies, the closest queers, more than his friends, his "loves," as Lemebel said, remember his deliberate and unmistakable tapping of his heels in a popular Chile that refuses to forget his combative and unmistakable voice.

READ ALSO: [ #Chile: Bachelet pledged to pass an equal marriage law ]

Jaime Lepé, a drag artist known for his character "Dajme" and a close friend of Pedro, speaks of this eternal time without Lemebel. A fellow traveler and performer, he expresses himself with confidence and emotion.

“People feel the absence of his subtle political irony. On the one hand, he would have been relentless in his criticism of right-wing businessmen financing their political proxies, a situation that has been exposed during his absence, and the ruling party wouldn't have been spared either, although he would have been more cautious with the president,” Jaime states, adding: “Without explicitly stating it in his writing or publicly, Pedro Lemebel was a Bachelet supporter from his non-militant but liberal communist perspective.”

Photo: Álvaro Hoppe

Lemebeleando everything

Constanza Farías worked with Pedro for the last few years, projecting sounds and vocal tones in Lemebel's artistic and public presentations. The chronicler, writer, visual artist, and 2014 National Literature Prize nominee called them "Chronicle-show."

“The city no longer sounds without you, it remained in stiff silence, in fascist silence. The sky bleeds without your tree shadow and the sun burns like that day you left,” says Constanza.

“I keep the sound intact of what was told, some sad afternoons I relive those stories while walking through downtown Santiago, I still feel the warmth of your arm taking refuge in mine and I conclude: It is evident, you made everything Lemebel, the walls, the streets and inevitably your friends,” reflects Lemebel’s friend and sound engineer accomplice.

Transgressing the times

For her part, Toli Hernández, a lesbian feminist activist, points out that “Lemebel has remained present and active because his work transcends time. In that transgression lies the legacy he leaves to sexual dissidence. His work is, above all, an example of resistance, since it cannot be forgotten that it emerged in the midst of a dictatorship and that this was not something simple, because it was a matter of life or death.”

Toli recalls the times of Pedro Lemebel and Francisco Casas with the cultural collective: “Las Yeguas del Apocalipsis” (The Mares of the Apocalypse). “Lemebel and Casas put their bodies on the line, and that wasn't easy for a Chilean queer person. Their work is an example of resistance because it not only shows realities unknown at the time, but also because it questions the post-dictatorial order that was being established and that brought into play the perverse confluence between state/civil society/neoliberalism,” Hernández analyzes.

Toli recalls the times when Lemebel supported actions of the sexual diversity movement, particularly lesbian, because beyond his critical view of LGBTI agendas, what mattered was the urgency, the solidarity.

[READ ALSO: Trans children in Chile, at the center of parliamentary debate ]

“I suppose it’s the identification with the feminine that she defended and that made her a dissenting voice alongside her lesbian feminist comrades in the Ayuquelén collective. In addition to fighting for the repeal of Article 365 of the Chilean Penal Code, which penalized sodomitic practices between adult men with imprisonment, Las Yeguas del Apocalipsis and Ayuquelén defended a broader struggle,” says Hernández.

“In his work, Lemebel explored structural variables of oppression that go beyond the sexuality championed by the LGBTQ+ movement. Pedro intertwined sexuality, gender, and class—a perspective that was lost within this movement but which connects him to the development of Latin American lesbian feminist thought, especially that which places lesbian oppression within a broader framework for understanding reality,” adds Toli Hernández. “This is a legacy that brings his contributions into the present and also calls for a re-reading of his works,” she says.

Lemebel and Víctor Hugo Robles

Pedro monumented

Cristián Condemarzo, poet, performance artist, and “peripheral writer,” as he likes to be called, responds: “Lemebel inherits a field of action, a discursive platform, a desire for radicalism, a history with its pants down, he inherits the possibility of being queen in a sandcastle and the fortune of leaving without being forgotten,” he says. “And don’t let him inherit too much, girl, if the others have to get to work. There’s a long road ahead to travel in heels,” he exhorts.

Regarding the need for and cultural, historical, and hysterical importance of a controversial monument to Pedro Lemebel in Recoleta, Condemarzo emphasizes: “It’s better to have a monument to literature than a shopping mall, although Pedro Lemebel doesn’t need monuments, those who come after him do. I assume there’s no sainthood without the media attention, but memory is created by people. It’s our responsibility to breathe life into that lifeless marble,” Condemarzo concludes.

Lemebel and Robles at the 1995 Gay Pride March. Photo: Álvaro Hoppe

Toli Hernández, delving deeper into the controversy, points out: “I want to emphasize that ‘monumenting’ Pedro is unsettling because the interpretation of his figure can be linked to the dominant view of sexual diversity, and Pedro was always countercultural. The LGBTQ+ hegemony must have applauded this initiative because it interprets it as an endorsement of its achievements and demands, which fall within the limited democratic margins in which they operate.”

In September 2016, the Chamber of Deputies approved the erection of a monument to Pedro Lemebel, with 90 votes in favor and 18 abstentions (from the Pinochet-era Independent Democratic Union party, UDI). The Movement for Homosexual Liberation and Integration (Movilh) declared, with satisfaction: "It honors someone who contributed to dismantling homophobia and classism with his unique, renowned, and award-winning writing."

The tribute of the madwomen

Alejandro Modarelli, an Argentine journalist and writer who visited Santiago de Chile these days , shared and dialogued with the crazy friends of Pedro Lemebel, weaving complicity with a group of queers who remembered –we remember– with stubbornness the political-cultural legacy of the artist and homosexual activist.

Regarding his political, literary, and friendly relationship with Pedro Lemebel, Modarelli acknowledges: “I always say that I returned to writing literature under Pedro’s splendid influence. Which doesn’t mean I was trapped by his style, but rather captivated by it. A style is an unconscious sum of influences, and alongside that stony mark are so many other influences from the literary tradition.”

"Blessed is the madwoman who flees from her mother," Modarelli reflects, recalling the Cuban Lezama Lima in this literary exile.

Diversity March, Santiago, Chile, 2007. Photo: Johnny Aguirre

“I hope my foster mother (Lemebel) has been able to let go and continue on my own path, although of course, she was always controlling and must still be around, critical. What I do hope is that, from wherever she is, she grants me the gift of publicly maintaining a critical perspective on homosexuality and the triumphant gay model. Because, as the older generation would say, where will we end up with so much eagerness to assimilate? In the end, even with a suit, tie, and wedding planner—as an Argentinian gay friend told me—they still get burned by that epithet, ‘fucking faggot,’” Modarelli says.

[READ ALSO: Modarelli: “The Latin American queer adventure is in danger” ]

We stayed in Santiago, while our country burned, inhabiting the city without Pedro, sadder and lonelier, as his Mina . A more neoliberal and social-climbing city. A city that evokes and summons in its narrow streets a daring march of student, labor, feminist, Mapuche, environmental, and identity-based causes, fighting, battling, persisting, and insisting alongside our mad revolution.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.

Without a doubt, Lemebel was more than a chronicler, a poet, a transgressor… and his work is among the best universally speaking… What I most admire about him as a person is that he was a grassroots activist!