Hate speech is offensive, discriminatory or harmful expressions against a person or group because of their religion, origin, race, gender or any other inherent part of their identity.

At their worst, these messages can cross the threshold of incitement to violence, like those that precede the most atrocious crimes of today.

Hate speech has a double effect : it diminishes or dehumanizes its target while reinforcing the ideas of those who think alike and tells them they are not alone. In Peru, politicians, religious leaders, the press and citizens promote this kind of speech against LGBTI people.

During the years of terror, incitement to hate LGBTI people escalated. Subversive groups persecuted, tortured and executed an unknown number of trans and homosexual women in the Peruvian jungle, deeming them immoral for society. Crimes that for the IACHR classify as violence due to prejudice.

The Peruvian State has not investigated the scale of hate; it does not know how many LGBTI victims were in the Amazon. This report gathers unpublished testimonies from trans and homosexual people who resisted the years of terror, but it also narrates the advance of anti-trans hatred promoted by new executioners.

The silenced crimes

Hate speech and hate crimes against LGBTI people in the Peruvian Amazon

June, 2023

This is a project by Elizabeth Salazar and Marco Garro, produced in partnership with

the

Pulitzer Center

In the beginning of 2021 in Peru, the last stretch of the presidential race was disputed between right-wing candidate Keiko Fujimori and leftist Pedro Castillo. The campaign was characterized by the political use of fear, with messages that linked a triumph of the left with an imminent return to the terrorist violence that plagued the country from 1980 to 2000. It featured the growing use of terruqueo, the practice of discrediting those who promote political plurality or challenge the system of government by accusing them of being terrorists.

Five hundred kilometers from the capital, in the district of Yarinacocha in the jungle region Ucayali, Sandra Tuanama Tenazoa went to work at her hair salon under the condition that no news played. She was tired of the election. But rumors and misinformation crept into her business from her own clients. Like the time a man whose hair she was cutting told her: “I hope Castillo wins so that you all disappear. They say one of his campaign promises is to kill all the fags.” Sandra, who’s an activist and leader of the Yarinacocha Trans Women's Network (Remutic), only managed to reply: "You can’t wish that on anyone. How would you like it if they did that to your son?"

Sandra was a teenager in the late 1980s, when the Shining Path and the Tupac Amaru Revolutionary Movement (MRTA) intensified their terrorist attacks in the Peruvian jungle and began a period of persecution and killing of trans and homosexual people. Around her, people talked about those who had been murdered and at home she was warned about when she should stay inside to hide from the subversive patrols.

The 2021 presidential campaign brought back those memories. No matter who won, Sandra figured trans women would wind up in the crosshairs. So when the press reported that a narcoterrorist group murdered 16 people in the neighboring region of Junín, just days before the second round vote, the trans leader believed they would go after them next. She wrote to her friends on WhatsApp and informed them that the network’s meetings were suspended for security reasons.

“The rumors were that they (the terrorists) already knew where we hung out. That they were going to show up and they were going to beat us…I told the girls to take care of themselves as best they could and that maybe when this government was over we would meet again. Or maybe not, and some of us would die. No one knew what would happen…”

Sandra Tuanama

Leader of the Yarinacocha Trans Women's Network

Sandra entered her hair salon, took the scissors and, in front of the mirror, cut her hair to the nape of her neck. Her friends followed her example and got rid of their long hair, which to them was a symbol of their gender identity. They traded crop tops for baggy T-shirts, leggings for chunky jeans. They ended their nights out and deleted old pictures from social media. They began to hide without makeup.

“I cut my hair because I wanted to, not out of fear or insecurity…but who isn't afraid of dying? We’re human beings and we’re afraid. I have a father and a mother, and if they kill me, they will suffer too. Since we live in a society that discriminates against the (trans) population so much, you have to be afraid”.

Sandra Tuanama

Leader of the Yarinacocha Trans Women's Network

Fear is sustained by the recent past, but also by oblivion. An uncalculated number of lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and intersex (LGBTI) people were persecuted, tortured and executed in the Peruvian jungle during the internal armed conflict. However, more than two decades later, the State has not made a historical compilation of these events to gauge the scope of the hatred.

This report gathers the unpublished voices of trans and homosexual women who survived terrorist violence in the Amazon. They include people from the regions of Loreto, Ucayali and San Martin who witnessed or suffered systematic violations of their human rights, and who have not had the opportunity to be heard or compensated by the authorities to process what they lived.

In addition, for the first time, details of the only two cases to reach the courts are revealed, showing that the terrorist crimes against sexual diversity were not isolated events. There is a file in which the former leaders of subversive groups are accused, though they still have not been sentenced. All this comes amid the current context of growing discrimination against the LGBTI community at a time when the new perpetrators of violence no longer need to wear ski masks or rifles.

Pucallpa: persecution and death

Chapter I

The Lupuna is one of the green giants of the Amazon. A tree that can reach 70 meters in height and to which medicinal properties and mythical beliefs are attributed. One lupuna has stood for more than 200 years in Pucallpa in the Ucayali region, and is the tourist attraction of a park that bears its name. However, the bullet marks on its trunk tell another story: at its feet fell the corpses of alleged thieves, drug addicts, prostitutes and homosexuals who were shot down by terrorists in the late 1980s.

Romy Ramírez Vela was 28 years old when he escaped that fate. It was 1989 and he lived at his parents' house, almost in secret, because when night fell the subversive patrols went through the area to catch homosexuals. He only went out to buy groceries, but that afternoon he slipped away to meet his boyfriend. On their way back, they stopped to talk near his house and did not notice that a truck with half a dozen armed men was approaching.

The vehicle slowed down and one of the occupants reached out to brush the shoulders of Romy, who had long hair. His short, high-pitched yell made the terrorist jump out of the truck. He drew his gun, pointed it at his head and yelled: “Run, motherfucker, run!” Romy ran without looking back. He reached his house with a tiny voice, asking his mother to open the door. His boyfriend, who watched as they kept a gun pointed at Romy, was told that if they were seen together again, they were going to be shot, one behind the other's back.

“The terrorists would cut your throat. They had no mercy. The dead appeared on street corners, especially low-life people, as they called women who cheated on their husbands, thieves, homosexuals…The terrorists had a black list with the names of the people who they were going to shoot…They were taken from their homes, from parties, killed and thrown at the Lupuna tree. They dumped the dead there."

Romy Ramírez Vela (61)

Hairdresser from Pucallpa

More than two decades have passed since terrorist groups ceased to be a threat to residents. Romy lives in the same neighborhood and to get to his house he has to cross the Lupuna tree, a permanent reminder of his survival and of those who did not make it.

The first official document confirming these crimes was the report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (CVR), a working group created to analyze the armed conflict and come up with proposals for reparations, which this year turned into two decades of publication. The text was published in 2003 and narrates how subversive groups applied a "social cleansing" policy against those they considered undesirable in the community, for example, LGBTI people. Sociologist José Montalvo Cifuentes attributed the policy to the cultural mandates and ideological extremism promoted by the armed organizations.

The CVR report takes place in nine volumes, but the violence against LGBTI persons is described in just a couple of pages and identifies four cases. Tito Bracamonte, the former executive secretary of the National Human Rights Coordinator (CNDH) and the former president of the Lima Homosexual Movement (Mhol), recalls that the inclusion of these crimes in the official document was almost accidental, coming a few months before the final text was published.

“In 2003, Mhol held a public vigil to denounce crimes against the LGBTI community. An altar was erected with photos of victims and it included those of the massacre at the Las Gardenias nightclub (in Tarapoto, San Martín), which had appeared in the press at that time. The Truth Commission team, which was about to publish their report, saw it and asked their team to cross-reference their data with the names we showed,” Bracamonte said.

It didn't take long for the commission's investigators to corroborate that one of the murders mentioned in the Mhol's exhibit was in its database of terrorism crimes. The problem was they had not considered the gender identity of the victims, only their legal names. After reviewing their interviews, they were able to corroborate and add the four cases to their report.

This Lupuna tree was used as a platform for terror in Pucallpa. At its feet the corpses of alleged thieves, drug addicts, prostitutes and homosexuals piled up.

These were the massacres in the district of Aucayacu, Huánuco, in 1986; in the La Hoyada sector of Pucallpa in 1988; two crimes in the city of Tarapoto, San Martín, in 1989, when a sign that read "this is how faggots die” was found with the body of one of the victims, and the massacre at the Las Gardenias nightclub on May 31, 1989, among whose victims were members of the LGBTI community. In commemoration of the victims at Las Gardenias, May 31 became the National Day against Hate Crimes.

These cases —along with the testimony given in 2008 by survivor Roger Pinchi Vásquez before the Ministry of Justice about what happened to him and his sister Fransua Pinchi— are the only ones recognized by the Peruvian government as violations of the human rights of LGBTI people during the years of terror. They have served as the basis for academic and journalistic articles, and are remembered on commemorative dates. However, they are not the only ones.

The testimonies gathered in this report coincide in that the worst persecution occurred in the La Hoyada sector, a riverside strip taken over by crime but where trans and homosexual people had set up courts to play volleyball without feeling judged. Here, on September 12 of 1988, one of the four massacres described in the CVR report took place. On that day, journalists were summoned by members of the Shining Path to witness public shootings.

“It was 5:30 am when a group of the Shining Path appeared carrying eight people, men and women, whom they lined up. Immediately three men armed with submachine guns fired bursts of bullets at them," the document states. According to the information collected by the CVR, one of the journalists who arrived to the area reported that the victims "were stoners, fags and prostitutes." The bodies —adds the report— ended up in a common grave and no one claimed them.

La Hoyada was both a gallows and an escape valve for members of the LGBTI community. Dozens of trans and homosexual people formed queues on the shore to board boats that would take them to the neighboring Amazonian city of Iquitos, in the Loreto region, which, lacking land access, promised a temporary refuge from the advance of terror. In the neighborhood, residents remember saying goodbye to friends who were forced to migrate from 1985 and 1990 after hearing their names had been included on kill lists.

Although the main executioner of gender identity in La Hoyada was the Shining Path, the MRTA also terrorized the LGBTI community. An article from the now defunct daily Página Libre, dated July 19, 1990, refers to the torture of two young homosexuals. "These individuals had been taken to dark places by MRTA members, who, after beating them severely and threatening them with death for continuing their street activities, stole their belongings, leaving them naked and tied to a tree," the story reads.

One resident who lived in this area during the years of terror is Sergio Venegas, a fashion designer known well in Pucallpa for the stunning gala dresses he creates for LGBTI pageants and parades. There, among sequins and bundles of fabrics that create his world of glamor, his young children play and run after the family dog. “Our parents raised us saying that we had to have children no matter what. I do have children and I am very proud of them. They love and adore me just the way I am. I no longer have to hide or be ashamed of anything,” he said. “As you can see, I tend to be a little macho. I'm not super flamboyant. But for many years I couldn't be myself and that was really hard.”

Sergio remembers that he had to enlist in the Peruvian Navy at the age of 17 to hide from Sendero Luminoso, while its militants were looking for young people on the cusp of adulthood to integrate into their ranks. They transferred him to the Iquitos Naval Base, in the Loreto region, to do administrative work for two years. It was there, in the barracks, where he learned to fight back when someone suggested he was gay. He changed his voice and suppressed his behavior.

“I’ve done many things to survive. I did my military service to hide, to take care of myself and safeguard my life,” he said. “I had to be aware of my attitude. I couldn't be me…day-to-day life has made me who I am: I am a father, I have children, but I am part of the LGBTI community and I am not ashamed of that. I am still the mother, the grandmother, the aunt.”

Sergio Venegas Cavalcanti (54)

Fashion designer

When he returned to La Hoyada, insurgent groups had expanded. Volleyball championships, an integrating activity for the LGBTI community, became activities of identification and death. Infiltrated terrorists sat in the crowd to observe them to inquire about their gender identity. They wanted to know if anyone practiced prostitution or dressed in feminine clothes at night.

Sergio had to deny being gay. He remembers that, on two occasions, strangers pointed a gun at him on the way home, warning that they did not want to see him "walking the streets", and he knew about people who refused to hide their gender identity and were killed and thrown in the Ucayali river or found dead on the streets of Espinar, El Arenal, and what used to be the Pacacocha sector. The data included in the CVR report indicates that "most of the corpses (of LGBTI people) were thrown into rivers and dumps."

Sociologists like Montalvo Cifuentes who have analyzed terrorist violence say the Shining Path took advantage of existing prejudices in society to justify their crimes. Their slogan was to eliminate those they considered "social scourges," appealing for support from those who shared that view. And they found it. “A sector of the residents accepted (the murders) as beneficial, since it gave them greater security and peace of mind. Social demand led some places to seek the presence of the Shining Path to carry out cleansing campaigns,” the CVR report states.

According to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR), "when crimes against LGBTI persons happens, these are often preceded by a context of high dehumanization and discrimination."

This backing and the stigma against LGBTI people led the relatives of the victims and survivors to adopt low-profiles and not bother to seek justice. “They were buried as men, without using their women names. They didn’t want to admit or let it be known that their family member was gay,” Romy Ramírez recalls. The word interviewees used the most when they describing why they kept quiet was “shame.”

Some survivors point out that their attitudes and appearance were different from the behavior of LGBTI people who were murdered. Some describe the victims as "rebellious" or "disobedient" for not hiding their trans identity during the years of terror, especially if they had to resort to street prostitution to support themselves. Others say they were spared execution because they had socially accepted jobs or took care of their parents.

I worked as a cook in Tocache (San Martín region). Nothing serious ever happened to me. I lost a few friends over there, but what can you do? Life is like that. They didn’t get it…They wound up massacred. Dragged and killed for rebellion. They were told to behave. What did that mean? Don’t make trouble. Go from work to home. You couldn't walk about all transformed…I only went so far as to play with dyeing my hair, but I kept it short. I put on a hat and that was it.

Jorge ‘Pilancha’ (62)

Former cook and hairdresser

I was returning from a night volleyball tournament when terrorism got me. They put a gun at the nape of my neck and made me walk from the Manantay district to my house. They knew everything about my life: where I worked, how many siblings I had, who my friends were. Everything…They wouldn’t kill us when they saw we had jobs and were supporting our parents. If we weren't involved in prostitution, drugs or robbery, they’d let us live. At least that’s what they said.

Jairo Tapullima Viteri (55)

Hairdresser

When the period of violence ended, Sergio baptized his sewing workshop as Casa Hogar Niño Gay, the Gay Boy’s Home, and provided temporary housing there to gay people who were forced to leave abusive homes. He participates as a health promoter in HIV prevention and treatment projects in his community. Balancing his activism with the glamour of fashion shows, he says he turned fear into resistance.

The same context of violence prompted his friend Carlos Vilca Abal to found the Equality and Future Cultural Movement (Mocifú) in 2007. His objective, he says, is to train members of the LGBTI community from Pucallpa on human rights, leadership and health issues so such crimes are not repeated. “I always remember the case of a trans girl named Vicky. They had threatened her because she went out dressed as a woman. In 1991 her throat was slit and her body was dumped near a volleyball court. That's how it was in those years: we’d be playing one day and mourning the next,” he recalls.

Through volleyball, Vilca Abal connects with young people in vulnerable situations and invites them to take part in his workshops. But in the 2021 electoral campaign, when rumors of the return of terrorism spread, they stopped going to sports fields.

Iquitos: Lives in need of reparations

Chapter II

Iquitos, the capital of Loreto, became a destination for LGBTI people fleeing subversive groups, due to its inaccessibility by land. Rita León, founder of the Homosexual Community of Hope for the Loreto Region (Cherl), recalls that she took in trans and homosexual people from Yurimaguas, Pucallpa, Tarapoto and the border areas. “Many cut their hair and had to assume another personality so they wouldn't be recognized. They tried to hide. When it was all over, some returned to their regions, but most stayed,” she says.

In the second half of the period of terrorist violence, in the 1990s, the spread of HIV and AIDS was an additional factor of discrimination and prejudice against LGBTI people, especially in the Amazon. According to data from the Ministry of Health's National Center for Epidemiology, Prevention and Control of Diseases, after 1987 the number of people diagnosed began to grow steadily and reached historic records in 1996 and 1997. Official statistics show that Loreto was one of the five regions with the highest incidence of new cases.

“We began to be the plagued ones. If we arrived at a health center with bruises or a fever, they assumed that we had HIV, even though the virus is not exclusive to the LGBTI community…Those who fell ill were abandoned by their relatives. We took care of each other…every week we buried about ten friends. This was the second massacre we were facing."

Rita León

Founder of the Homosexual Community of Hope for the Loreto Region (Cherl)

Although the ravages of HIV are remembered more widely in Loreto, members of the LGBTI community from Iquitos who migrated to other areas were also affected by terrorism. They include trans and gay people who left Iquitos to escape abuse at home or to find a better environment in which to express their gender identity, and who wound up in regions that became the focus of violence.

One of them is Denisse Vásquez, who left her neighborhood for a false job offer and ended up being exploited as a cook in Tocache, San Martín, a city that was once controlled by drug trafficking and terrorist groups. Her gender identity was used as a weapon of coercion: if she opposed the conditions of semi-slavery to which she was subjected, her captors threatened to hand her over to the Shining Path.

Denisse spent a decade fleeing from the cities of Tocache, Tarapoto and Yurimaguas, until she arrived to Lima. When she tells us this in an interview, she gets up to look for an old photo album. Her silver-painted nails flip through its pages until she finds a portrait of herself in a tight black dress, her hair falling over her shoulders. “I arrived in Lima like this. Like a lady. This is the last photo I took before getting surgery and removing all my prostheses. I was afraid the terrorists were after me. I didn't want to be identified or killed,” she says.

After a long stay in the capital, and after terrorism had been eradicated from her hometown, she returned to Iquitos. “In Lima everyone said things were more peaceful, but I kept feeling they would come for me,” she said. “Until I was 35 or 40 years old, all my memories were what I saw in Tocache. The ugliest memory—just thinking about it brings me to tears…We were leaving a bar with my girlfriends. I stepped out and that's when the shots started. People ran. I ran, too. They killed my friends right in front of me. They dragged them with ropes down the street, dead, to throw them in the river. The next day I fled."

In 2018, the High-Level Multisectoral Commission (CMAN), an entity of the Ministry of Justice (Minjus) in charge of reparations for health, education and economic matters for the bereaved and survivors of the armed internal conflict, published the technical guidelines for officials to give reparations with a focus on gender. The document, however, does not include a protocol for mental health care for LGBTI people who live with trauma.

The text assigns the Ministry of Health (Minsa) and the Ministry of Women and Vulnerable Populations (MIMP) the responsibility of physically and psychologically assisting women who were violated in those years, but no specific functions for the LGBTI were drafted. We requested interviews with both ministries to ask about their actions regarding reparations but they did not reply.

CMAN said that in 2020 it asked the ministries to provide an update on the application of a gender focus for their Reparations Plan, but no one responded. However, it added that in 2018 a ceremony was held in Tarapoto in which a public apology was offered to the LGBTI community "for the effects suffered."

Ari Jáuregui, a sociologist and LGBTI activist, says a commemorative plaque does not help survivors who may not even be recognized by their families due to homophobia or transphobia. Jáuregui says the State should offer financial reparations and comprehensive care to survivors, develop clear plans to address their complaints, and stop tolerating the persecution promoted by anti-rights groups.

“What do we do when the people who persecute us are in power? We must address the trans-hating and homophobic discourses that come from the State itself, where conservative and anti-right groups persecute our existence,” they say. Jáuregui says LGBTI voices must be positioned in the collective memory of discrimination and hate crimes, since they are not events of the past, but violence that the community continues to face.

The trans women who were murdered are remembered in the LGBTI community by the names that honor their gender identity: Vicky, Pilar, Andrea, Reyna and many more who, in life or death, did not exist for the State, since few in Peru manage to get their names changed on official identity documents.

The first step to respecting the memory of the victims of hate crimes is naming them. But Leyla Huerta, a transgender activist and founder of the organization Féminas, says that in the absence of a gender identity law in Peru, trans women are forced to go through humiliating and discriminatory trials. When one finally gets a favorable ruling, the civil registry office appeals and prolongs its claim.

Colombia is ahead of Peru in hearing the voices of LGBTI people who suffered violence, at least in regards to crimes produced during the internal armed conflict. In 2014, the country’s justice system issued a historic ruling and sanctioned paramilitary groups for the murder of LGBTI people, and in 2022 its Truth Commission became the first to recognize LGBTI people as victims of the conflict.

According to the Unit for Comprehensive Care and Reparation for Victims in Colombia, to date 5,137 LGBTI people have been identified who were attacked during this period. In Peru, the Single Registry of Victims (RUV) that was created to identify and provide reparations for communities, survivors, and relatives of the years of terror does not take gender identity into consideration. The registry contains more than 228,000 names classified as male or female.

Katherine Valenzuela Jiménez, executive secretary of CMAN, said the registry was built with data from the CVR, and no progress was made in identifying more LGBTI victims because officials were not trained to register trans people who lacked identity documents. "In 2020, local governments began to train local registrars to reach more victims, but the pandemic paralyzed their progress…we know the State is indebted to the LGBTI community and we apologize for it," she added.

Although the RUV does not distinguish the gender identity of the registered victims, documents obtained through requests for access to information to justice ministry showed that of the more than 228,000 registered victims, six were LGBTI cases. The list is made up of the siblings Roger and Fransua Pinchi Vásquez, and their mother; and for two of the deceased in the Las Gardenias nightclub and one of their family members.

Tarapoto: the trial without sentence

Chapter III

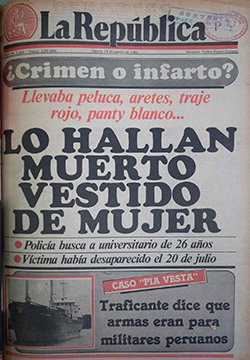

Roger Pinchi Vásquez, a former schoolteacher from the city of Tarapoto in the San Martín region, is the only LGBTI survivor that the Peruvian state identified in its list of terror victims. His name appears in the RUV because he himself appeared before authorities in 2008 to describe how terrorism affected his family, when his sister Fransua Pinchi Vásquez was kidnapped and killed with a bullet to the stomach by members of the MRTA.

The crime occurred on September 20, 1990 and was covered by the Tarapoto press because Fransua was one of the first trans women in town, as well as a well-known hairdresser and beauty salon businesswoman. But her death appears in the CVR database with her birth name. It took almost 19 years for the State to recognize her because of her gender identity, and it only did so because of her brother’s testimony.

It was not until 2018 that Roger Pinchi returned to tell the authorities that he too had been a victim. Months before the crime in Fransua, the MRTA members kidnapped him and tortured him for eight days because they mistook him for her. In the attack, his wife was stabbed and she still suffers from related health problems today. He identifies as gay, but says that with the escalating violence he felt it was necessary to marry to hide his identity.

In 2018, the State included him in the list of reparations and granted him 10,000 soles in compensation, about $3,000, which was quickly diluted by the medical needs of his wife, unemployment, and the care of his mother until she passed away. The family did not receive any other social or psychological support. “I had to admit my wife to a hospital in Lima. Because of my prolonged absence, I lost my job as a teacher. We don’t have a house or stable work. We rent. I worked selling food, then as a hairdresser. I have nothing left,” he says.

“They kidnapped me by mistake,” he says. “They kept me there for eight days, with beatings, physical and psychological abuse. In the end they even raped me there. A person who knew me showed up, lifted my face to look at me and saw I wasn’t my sister. That's when they released me."

Roger Pinchi Vásquez

Survivor. Testimony before the Place of Memory (LUM)

Academics, photographers and journalists, like Amanda Meza and Antonio López, as well as the filmmaker Juan Carlos Goicochea, who is working on a documentary, have explored the terrorist violence perpetrated against sexual diversity in Tarapoto based on the murder of Fransua Pinchi Vásquez and the massacre at the Las Gardenias nightclub. The two cases are particularly important since they are the only ones to reach the Peruvian courts to seek justice for LGBTI victims during the period of terror.

This report exposes, for the first time, the details of the investigation led by the Second Supraprovincial Criminal Prosecutor's Office for seven years, which was formalized before the Judiciary on May 31, 2021, the National Day against Hate Crimes. File 00186-2021, more than 170 pages long, argues that the murders were part of MRTA’s extermination policy against homosexual community. Other groups of sexual diversity were not included and the Shining Path is not part of the investigation.

It accuses five of the MRTA’s former leaders—Víctor Polay Campos, Miguel Ríncon Rincón, María Cumpa Miranda and Alberto Gálvez Olachea and Peter Cárdenas Schulte—of being the masterminds of the murders, and accuses 12 local members of MRTA if carrying them out. The former MRTA leaders are all serving prison terms, except for Cárdenas, who left the country upon completing his. They are only accused of homicide and terrorism because in Peru there is no specific law for punishing hate crimes.

But according to the prosecutor's thesis, both crimes were systematic practices carried out to instill fear. “They were part of a generalized and systematic practice against the civilian population, constituting crimes against dignity,” it says. “These acts are a serious violation of human rights to the detriment of a defined and specific human group of the civilian population: the homosexual community.”

“Fransua was a symbolic death, like a trophy for MRTA. From there came the massive exodus of homosexual people. They went back to their farms. They disappeared because they thought that the attack against Fransua would bring to more deaths….many homosexuals even enlisted in the Army in hope of salvation.”

Testimony included in File 00186-2021

To support their case, the prosecution gathered witnesses and identified two other crimes against homosexuals in that town. The first was the homicide of Salomón Pérez Armas, who was kidnapped by an MRTA group when he was leaving a friend's house. On July 12, 1992, his body was found in a ditch, with a cable tied around his neck and a bullet in his skull. According to the file, days before his death, Pérez Armas received a flyer that read: “MRTA – You are given a period of 15 days to vacate Tarapoto for being a scourge of society. If you fail to comply with this note, you will be killed and dragged like dogs.”

The second victim was Silvano Vela Carbajal, who was forcibly taken from his house in 1991 by a group of 14 MRTA members who shot him in the chest. The case was reconstructed by the prosecutor's office based on judicial process 125-00/SP, which in 1998 served to convict the now-deceased MRTA member Abel Pinedo Valles. In the file, his subordinates said he ordered Vela Carbajal’s killing because he was gay. The terrorists testified that their bosses hated LGBTI people. "They were looking for them to kill them,” they said. “We were just following orders.”

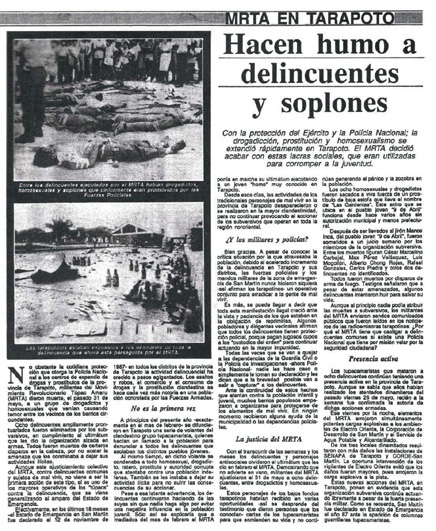

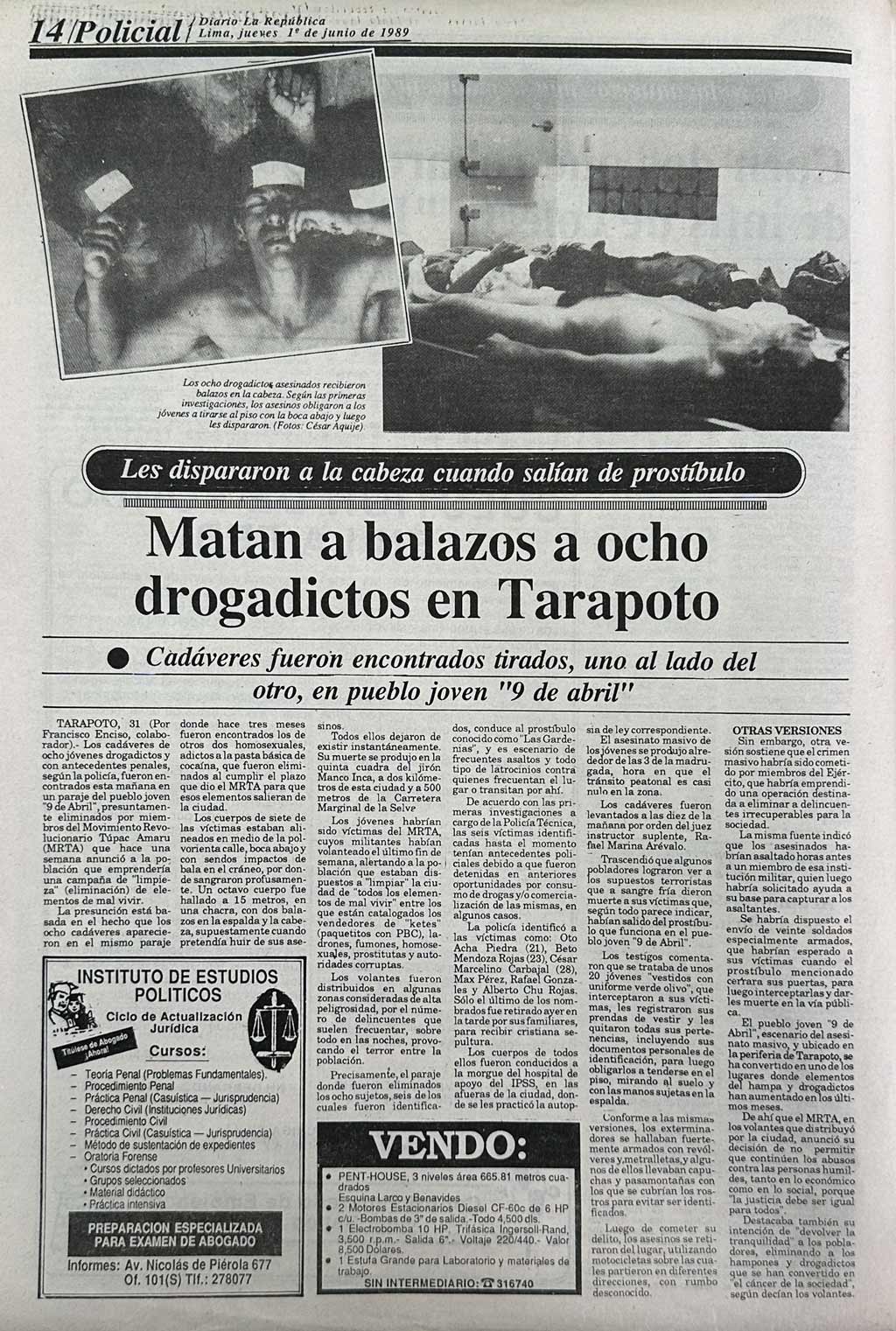

The file also includes police report 009-SE-JP, which was opened in 1989 after the massacre outside the Las Gardenias nightclub and was soon forgotten. It mentions a document seized at the crime scene that read: “Communiqué: with this (massacre) there are now 10 (dead) and that is how stoners, informants, thieves, homosexuals and rapists will continue to die. Homeland or death! Overcome! MRTA.” That day, eight bodies were found, seven lined up in front of the premises and one a few meters away, all face down. According to the autopsy, each had a bullet lodged in the skull.

The newspaper La República headlined the event as follows: "Eight drug addicts are killed with bullets." The story reported that the corpses appeared "in the same place where two other homosexuals addicted to cocaine paste were found three months ago and that were eliminated when the deadline given by the MRTA to leave the city expired.” The weekly publication Cambio, known as the unofficial gazette of the MRTA, was more specific and said it had killed "a group of drug addicts and homosexuals who had been causing fear among residents."

In their defense, MRTA members have denied that there was a policy of social cleansing or a directive against LGBTI people. Some members said certain crimes were actions taken by "Tarapoto MRTA militiamen who did not submit to party control." Regarding what happened in Las Gardenias, they deny that the weekly Cambio, which attributed the crime to the MRTA, was their propaganda outlet. They even alleged that among those murdered in the disco there were no trans or homosexual people.

The testimonies gathered by the prosecution indicate that the disco was the meeting point for homosexual and trans people. Only one family member of a victim who testified in the process said his relative was murdered for being a drug addict. The information collected by the Truth Commission and the Reparations Commission helped identify at least two LGBTI victims in the multiple homicide.

Two of the eight people murdered there were not identified in the autopsy and remain nameless. To confirm their names and offer them posthumous justice, the prosecution asked to exhume their bodies.

On March 18, 2022, the Transitory Supraprovincial Liquidating Criminal Court responded that the case was not in its jurisdiction and returned it to prosecutors. The decision was appealed and it began moving forward again until January 9, 2023, when National Prosecutor Patricia Benavides dismantled the system of prosecutors specialized in human rights, interculturality and terrorism. Since then, the prosecutors’ office has split up its functions: one group will be in charge human rights processes and others terrorism, even though crimes committed in the 1980s and 1990s require both approaches.

Benavides' decision occurred in the context of the demonstrations against the government of Dina Boluarte and weakened the team of prosecutors investigating deadly repression of protesters. But it also had an impact on the cases of Fransua Pinchi and Las Gardenias. The prosecutorial office in charge of the file, the only one that could grant justice to the LGBTI victims of terrorism, was dismantled and on March 9 had to transfer its work to the terrorism department. Since then, progress on the process is unknown.

New aggressors, the same victims

Chapter IV

It is no longer terrorism that persecutes, discriminates and murders LGBTI people. The perpetrators are hate and prejudice, and always were. The attackers do not wear ski masks or carry rifles, they are strangers who beat and shoot them in the middle of the street. They are relatives who mistreat them and expel them from home in rejection of their gender identity. They are couples who think they deserve violence. They are state security forces that humiliate and attack them. They are officials, politicians and religious people who spread discourses that dehumanize them. It is the press and society that mocks them.

In the case of Peregrina, the makers of her most violent memory were four young university students, residents of her neighborhood in Nauta, Loreto. They constantly intercepted her when they saw her coming home from school to harass her, shouting nicknames at her in a modulated voice or demanding that she behave like a man. It was 2013. She was 15 years old and had just started to identify as a woman.

One day, her screams were not enough. Peregrina was kidnapped and sexually abused by the four students in a hotel room whose owner did not find it strange that they entered with a minor. The medical examinations confirmed that the adolescent was severely injured by the objects that were inserted into her and she had to be hospitalized. The State did not take care of her psychological wounds. The prosecutor's office did not prosecute her attackers either.

A decade later, on February 27, 2022, the same brutality would terrorize her best friend, Pamela. It was early in the morning and she was woken by a sharp pain that made her scream. She couldn't get up and opened her eyes to see a man stabbing her in her own bed. The attack left scars on her arms, on her left shoulder, on her throat and on her chest. But it did not touch the image that she tattooed in honor of her deceased mother.

According to the version Pamela gave to the police, that night her partner came home with a friend for drinks. At some point in the early morning the guest took a knife and entered the room where she was resting. There he unleashed his hatred. The young woman managed to get away and seek help. “I was in shock. I didn't know how to process everything. The first few days I thought it was my fault, that perhaps this happened to me because I had a mundane life. But no, he hardly knew me… no person has the right to hurt or take the life of anyone else” Pamela says.

Almost a year earlier, in the same city of Nauta, another transgender woman was murdered at her cell phone stand. The body of Reina Fernández Villanueva, 27, was found at dawn on May 10, 2021 with multiple wounds, the longest and deepest around her neck. There were no signs of theft. What shocked the police the most was that the murderer dragged the body throughout the premises, leaving a trail of blood.

“The first thing I thought of was Reina. It could have been me,” says Pamela.

In Peru, especially in the Amazon, evangelical churches have achieved growing political and social power, allowing them to propagate their messages against gender identity and equality policies. Nauta is no exception. It is common to find followers of the Worldwide Missionary Movement (MMM) in markets and public squares preaching that LGBTI people need to be saved and that only Jesus Christ can restore peace to them.

Cayo Sinarahua Amasifuén is pastor of the congregation in this city and says they approach trans women to invite them to his church. They hand out fliers, biographies of their leaders, and read Bible verses to them. According to his words, they seek to "rehabilitate" them. For them, trans people, those who are attacked, humiliated and murdered, are the ones who must make amends.

"We are not their enemies nor do we hate them. We just want to make them see reality through words, make them see that they are doing wrong before God, because God created two sexes: male and female…They can be what they want, but they can’t teach that doctrine to others.”

Cayo Sinarahua

Pastor of the Worldwide Missionary Movement (MMM) in Nauta, Loreto

The sociologist Ari Jáuregui warns that this type of religious discourse is not exclusive to Peru. There are international organizations that finance an ultra-conservative and anti-rights agenda in different countries, with messages that dehumanize LGBTI people and validate the social prejudices that fuel violent acts. “From political, scientific and religious positions they mobilize against our existence and that must be denounced,” they say.

Violence due to prejudice exists and has been defined by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) as a social and ongoing phenomenon that results from the justification of negative perceptions and generalizations, including false ones, in situations that differ from what is normative. “Such violence requires a context of social complicity. It is directed towards specific social groups, such as LGBTI people, and it has a symbolic impact,” it indicates in its report Violence against Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, and Intersex Persons in America.

This type of violence, Jáuregui says, sends a message to society. “Hate crimes seek to terrorize LGBTI people. It is a way of showing the community who is in control, who can use violence. It is telling the other person: you cannot exist because I am not going to allow it. And this does not only affect the person who is violated, or those around her, but the entire community that receives the message,” they say.

Between 2018 and 2021 alone, the MIMP Women's Emergency Centers responded to 148 cases of physical violence and 60 cases of sexual violence against LGBTI people in Peru. In the same period, the National Police received 135 complaints for discriminatory acts in different regions. The figure does not include those who chose not to report assaults.

“I was born in a native community in the Lower Amazon. Six years ago, when I was a sex worker, I was brutally attacked. A client called me to go to the main square, but when we got to the room, he hit me. He almost killed me. He said he didn’t accept a trans girl.”

Angie (24)

Lower Amazonas, Loreto

“At 17, a couple assaulted me and left my face purple. I didn't want to go to the hospital because there was a lot of discrimination. Thank God I had some good friends. They put ice on it and took care of me until all the swelling went down…now I live with a partner who doesn't discriminate against me”.

Chris (27)

Iquitos, Loreto

“In May of 2021 I broke up with a partner because they seriously assaulted me. They started stalking me and threatening to kill me. I went to the Loreto Women's Emergency Center (CEM) to ask for protection, but when they saw my name on my identification card they said they were not trained to care for me. The police told me they could not prove that the perpetrator was my partner. I gave up”.

Valeria Alado

Professional stylist, Loreto

Luis Hernán Chávez was gay and a well known merchant in Yarinacocha. He was beaten to death with a hammer in 2014, when he was sleeping in his own home. The police attributed the crime to a robbery and closed the case. His family, which never accepted that Luis was homosexual, chose an old photo for his tombstone, which does not show his gender identity.

Luis Chávez Ramírez (1956 - 2014)

Pucallpa

Carol Ríos, the head of the association of trans women in Loreto and coordinator of the Transcendent Opportunities project, says violence is a daily reality in the community, so much so that many do not realize it until they are on the verge of death. The rejection of families, the lack of educational and job opportunities, the precariousness in which many are forced to live, and situations of exploitation and contempt from society are all normalized because many believe it is the price to pay for maintaining their identity.

“We demand equal rights. More spaces are needed so that trans people can develop at an educational and work level,” says Ríos. She is also an official in the Regional Government of Loreto, but in order to access and stay in the position she has had to fight against the stigmatization and ridicule of colleagues who believe that her presence embarrasses the institution.

The penal code does not recognize the legal figure of violence due to prejudice or hate crimes, so the killings of lesbians, gays, bisexuals, trans and intersex are hidden in official records as common injuries and homicides. Only since February 2023, with Bill 4228, have lawmakers debated making the motive an aggravating factor in a crime.

In Peru, there is also no official monitoring of hate crimes. In 2022, the Public Ministry released the first official investigation that analyzes violent crimes against 88 members of the LGBTI community between 2012 and 2021. It was only able to do so based on data from the LGBTI Rights Observatory at the Peruvian University Cayetano Heredia ( UPCH), which keeps a registry of the gender identity of victims.

One of the conclusions of the report is that 68.4 percent of the files analyzed contained signs of violence due to prejudice, but only in 2.2 percent of the cases the prosecutors in charge had considered sexual orientation as a likely factor behind the homicide. In most of the case files, a clear motive for killings was not identified or they attributed it to common crimes. Hate crimes are not on the radar of justice operators.

The 88 cases identified by the prosecution

Violent deaths of LGBTI people are lost in official statistics that classify them as male or female. After reviewing each fiscal folder and making specific inquiries, the Public Ministry was able to identify 88 cases of LGBTI victims between 2012 and 2021. A very small sample compared to the 14,843 homicides registered only between 2011 and 2017.

identified by the

prosecution

Violent deaths of LGBTI people are lost in official statistics that classify them as male or female. After reviewing each fiscal folder and making specific inquiries, the Public Ministry was able to identify 88 cases of LGBTI victims between 2012 and 2021. A very small sample compared to the 14,843 homicides registered only between 2011 and 2017.

37.5% of the victims were trans and 59.2% gay and lesbian.

29.6% of the victims died from a sharp object, 25% from suffocation.

The victims are from 19 regions. It was not possible to obtain information on the origin of two cases and four others were identified as foreigners.

Source: Public Ministry

In 2020, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR) set a precedent by sanctioning the Peruvian State for the arbitrary detention, torture, rape, and police discrimination of Azul Rojas Marín, an LGBTI person. The State offered a public apology to the survivor, but has not yet prosecuted those responsible as ordered by the court’s sentence. Also pending is the implementation of statistical monitoring of violence against sexual diversity and the approval of a protocol to administer justice when rights are violated.

Judge Elvira Álvarez, president of the Gender Justice Commission of the Judiciary, says that in 2022 a protocol for administering justice with a gender focus was published, but the State has not issued a similar document for the LGBTI population in particular, as ordered by the ruling in the Azul Rojas case. These guidelines will be mandatory in all areas, not just the judiciary.

The activist Leyla Huerta says that since the terrorist massacre, the Peruvian State still has not promoted policies to protect the rights and lives of LGBTI people, especially trans people. To the contrary, she warns of a consolidation of conservatism and discriminatory discourse from lawmakers and the Executive Branch. “We have to ask, what has the State done to recover the historical memory of the crimes committed against us in the years of terrorism, and those that continue to be committed against us? They held a ceremony in Tarapoto to apologize, nothing more. We want actions, not words."

In the first two months of 2023 alone, eight trans women were murdered in Peru, in the regions of La Libertad, Arequipa, Lima, Lambayeque, and Amazonas. The body of one was charred and thrown into a vacant lot. Another was found dead in a hotel with signs of torture, and a third was shot for refusing to pay a quota to pimping mafias.

This led to something unprecedented in the country: hundreds of trans women and sex workers came together and held their first demonstration against hate crimes. They marched through the streets of Lima and reached police headquarters demanding justice for the murders, protection for their lives and an end to discrimination. They are not willing to remain invisible to the authorities. Not in life or in death.

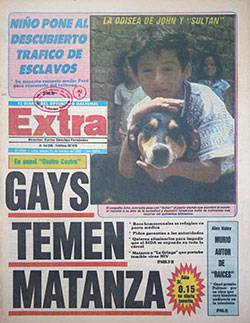

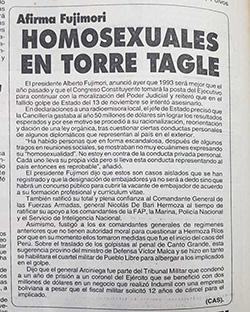

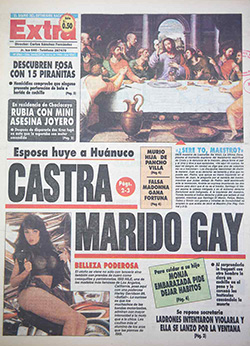

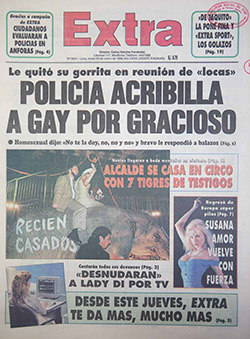

Hate continues to be written

This is a brief compilation of the murders, assaults and discrimination faced by LGBTI people in Peru that were reported on by the national press between 1986 and 2022. Violence against sexual diversity collectives is also manifested in the informative treatment given to these deaths.

Data collection: Carla Díaz

1986 / LIMA

Ataque de odio

1989 / PIURA

Ataque de odio

1990 / PUCALLPA

Ataque de odio

1990 / Lima

Ataque de odio

1991 / Lima

Ataque de odio

1992 / Lima

Discriminación

1993 / Lima

Discriminación

1994 / Lima

Ataque de odio

1995 / LIMA

Ataque de odio

1996 / Lima

Ataque de odio

1998 / Lima

Ataque de odio

1999 / LIMA

Discriminación

2000 / Lima

Ataque de odio

2002 / LIMA

Discriminación

2004 / Lima

Ataque de odio

2006 / Loreto

Ataque de odio

2008 / La Libertad

Ataque de odio

2008 La Libertad

Ataque de odio

Azul Rojas Marín, una mujer trans de 26 años, fue detenida arbitrariamente por agentes de la Policía Nacional, quienes la desnudaron, golpearon y violaron con una vara de uso policial.

2009 / San Martín

Ataque de odio

2009 San Martín

Ataque de odio

Techi, una joven trans, fue rapada, desnudada y golpeada con palos en la vía pública por la Junta Vecinal de Tarapoto, tras encontrarla teniendo relaciones sexuales con su acompañante.

2010 / LIMA

Ataque de odio

2010 Lima

Ataque de odio

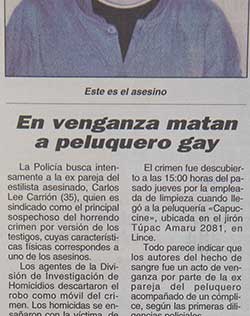

Felipe Antonio Ayllón Cabello, estilista homosexual de 34 años, fue asesinado en su peluquería con signos de haber sido golpeado y estrangulado.

2011 / LIMA

Discriminación

2011 Lima

Discriminación

Policías agrenden a gays y lesbianas que se besan frente a la Catedral de Lima durante la realización del evento 'Besos contra la homofobia'.

2011/ LIMA

Discurso de odio

2012 / LIMA

Ataque de odio

2012 Lima

Ataque de odio

Enrique Armestar Anci (27) fue asesinado y descuartizado. Sus restos fueron encontrados en una maleta.

2013 / Lima

Ataque de odio

2013 Lima

Ataque de odio

Yean Castillejo Pozo, mujer trans de 18 años, fue apuñalada en el estómago con un pico de botella. El ataque le provocó la pérdida de 6 c.m. de intestino.

2014 / Pucallpa

Ataque de odio

2014 Pucallpa

Ataque de odio

Luis Chávez Ramírez (58), un hombre homosexual, fue asesinado a martillazos en su casa. La nota de prensa invisibiliza su identidad de género.

Diario Impetu

2014 / LIMA

Discurso de odio

2014 Lima

Discurso de odio

El entonces parlamentario hizo estas declaraciones durante el debate en contra del proyecto de unión civil para parejas del mismo sexo.

2015 / Lima

Ataque de odio

2015 Lima

Ataque de odio

Manuel Damián Acuña Limache (40), a quien conocían como ‘Zafiro', fue asesinado a balazos en su peluquería ubicada en el Cercado de Lima.

2016 / La Libertad

Ataque de odio

2016 La Libertad

Ataque de odio

Zuleymi, una adolescente trans de 14 años, murió luego de recibir cuatro disparos.

2016 / Lima

Discriminación

2016 Lima

Discriminación

Policías golpean a gays y lesbianas que se besan en la Plaza de Armas durante la manifestación 'Besos contra la homofobia'.

2017 / Lima

Discurso de odio

2017 Lima

Discurso de odio

Durante un sermón, el líder evangélico señaló que las personas homosexuales "deben morir por no ser obra de Dios".

2018 / Junín

Ataque de odio

2018 Junín

Ataque de odio

Moisés Chicoma Ojeda (38), un hombre homosexual que trabajaba como barman, fue encontrado muerto en su casa de San Juan de Lurigancho, maniatado y desnudo, con signos de haber sido asfixiado.

2019 / Lima

Discriminación

2019 Lima

Discriminación

Sereno municipal agrede verbalmente a pareja homosexual que estaba abrazada en un parque.

2019 / San Martín

Ataque de odio

2019 San Martín

Ataque de odio

Padre mata a su hijo de 17 años por ser homosexual. Mientras le dispara reza para pedir perdón.

2020 Callao

Discriminación

2020 Callao

Discriminación

Durante el Estado de Emergencia por la Covid-19, policías obligan a mujeres trans a hacer ejercicios y decir "quiero ser hombre".

2021 / Lima

Discurso de odio

2021 Lima

Discurso de odio

El exasesor se pronunció en contra de la aplicación del enfoque de género en la educación, y como argumento dijo que "no se puede institucionalizar la homosexualidad".

2022 / Ayacucho

Ataque de odio

2022 Ayacucho

Ataque de odio

Mujer trans es atacada a patadas en la vía pública por un hombre, quien sería su pareja.

Silenced Crimes is a

project by

Elizabeth Salazar

and Marco Garro,

produced in partnership with the Pulitzer

Center

Text and investigation: Elizabeth Salazar Vega

Photographs and edition: Marco Garro Pardo

Web development: Fabrizio Piazze

Designer: Felipe Esparza

This work was coordinated by Agencia Presentes and Connectas for its final publication.